Episode #453: Whitney Baker on Why “Immaculate Disinflation” is an Illusion

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Guest: Whitney Baker is the founder of Totem Macro, which leverages extensive prior buyside experience to create unique research insights for an exclusive client-base of some of the world’s preeminent investors. Previously, Whitney worked for Bridgewater Associates as Head of Emerging Markets and for Soros Fund Management, co-managing an internal allocation with a dual Global Macro (cross-asset) and Global Long/Short Financial Equity mandate.

Date Recorded: 10/19/2022 | Run-Time: 1:17:46

Summary: In today’s episode, Whitney shares where she sees opportunity in at a time when, as she says, “we’re going from ‘risk-on cubed’ to ‘risk-off cubed’, starting from some of the highest valuations in history.” She touches on why she believes inflation is here to stay, the opportunity she sees today in emerging markets, and the dangers of using heuristics learned since 2008 to analyze the current market environment.

To listen to Whitney’s first appearance on The Meb Faber Show in January 2022, click here

Sponsor: AcreTrader – AcreTrader is an investment platform that makes it simple to own shares of farmland and earn passive income, and you can start investing in just minutes online. If you’re interested in a deeper understanding, and for more information on how to become a farmland investor through their platform, please visit acretrader.com/meb.

Comments or suggestions? Interested in sponsoring an episode? Email us [email protected]

Links from the Episode:

- 0:38 – Sponsor: AcreTrader

- 1:50 – Intro; Episode #387: Whitney Baker, Totem Macro

- 2:42 – Welcome back to our guest, Whitney Baker

- 4:22 – Whitney’s macro view of the world

- 12:30 – Scroll up for the chart referenced here

- 14:52 – Current thoughts on inflation as a macro volatility storm

- 15:58 – EconTalk podcast episode

- 18:41 – Why immaculate disinflation is a myth

- 24:58 – Whitney’s take on financial repression

- 30:20 – Does the Fed even want the current levels to come down?

- 34:01 – Episode #450: Harris “Kuppy” Kupperman; Thoughts on oil and its impact on inflation

- 41:08 – The state of emerging markets these days

- 47:32 – Whitney’s thesis on Taiwan

- 58:33 – Where we might see some stressors arise in the UK

- 1:06:09 – The biggest lie in economics is that an aging population is deflationary

- 1:09:37 – What most surprised Whitney the most in 2022

- 1:14:39 – Learn more about Whitney; Twitter; totemmacro.com

Transcript:

Welcome Message: Welcome to “The Meb Faber Show” where the focus is on helping you grow and preserve your wealth. Join us, as we discuss the craft of investing and uncover new and profitable ideas, all to help you grow wealthier and wiser. Better investing starts here.

Disclaimer: Meb Faber is the co-founder and chief investment officer at Cambria Investment Management. Due to industry regulations, he will not discuss any of Cambria’s funds on this podcast. All opinions expressed by podcast participants are solely their own opinions and do not reflect the opinion of Cambria Investment Management or its affiliates. For more information, visit cambriainvestments.com.

Sponsor Message: Today’s episode is sponsored by AcreTrader. In the first half of 2022, both stocks and bonds were down. You’ve heard us talk about the importance of diversifying beyond just stocks and bonds alone, and, if you’re looking for an asset that can help you diversify your portfolio and provide a potential hedge against inflation and rising food prices, look no further than farmland. Now, you may be thinking, “Meb, I don’t want to fly to a rural area, work with a broker I’ve never met before, spend hundreds of thousands or millions of dollars to buy a farm, and then go figure out how to run it myself. Nightmare,” but that’s where AcreTrader comes in. AcreTrader is an investing platform that makes it simple to own shares of agricultural land and earn passive income. They’ve recently added timberland to their offerings and they have one or two properties hitting the platform every week. So, you can start building a diverse ag land portfolio quickly and easily online.

I personally invested on AcreTrader and I can say it was an easy process. If you want to learn more about AcreTrader, check out Episode 312 when I spoke with founder Carter Malloy. And if you’re interested in a deeper understanding on how to become a farmland investor through their platform, please visit acretrader.com/meb. That’s acretrader.com/meb.

Meb: Welcome, podcast listeners. We got a special show for you today. Our returning guest is Whitney Baker, founder of Totem Macro and previously worked at shops like Bridgewater and Soros. If you missed our first episode back in January 2022, please, feel free to pause this, click the link in the show notes, and listen to that first. It was one of the most talked about episodes of the year.

In today’s episode, Whitney shares where she sees opportunity at a time when she says we’re going from risk on cubed to risk off cubed, starting from some of the highest valuations in history. She touches on why she believes inflation is here to stay, the opportunity she sees in emerging markets, and the dangers of using heuristics learned in past market cycles to analyze the current market environment. Please enjoy another awesome episode with Whitney Baker. Whitney, welcome back to the show.

Whitney: Thanks, Meb. Thanks for having me back.

Meb: We had you originally on in January, we got to hear a lot about your framework. So, listeners, go listen to that original episode for a little background. Today, we’re just going to kind of dive in. We got such great feedback, we thought we’d have you back on to talk all things macro in the world and EM and volatility. Because it’s been quite a year, I think it’s one of the worst years ever for U.S. stocks and bonds together. And so, I’ll let you begin. We’ll give you the…

Whitney: “Together” is the key thing there because, you know, normally, they help…you know, in the last world we’ve come out of, they’ve protected you a little bit and the bonds have protected you a little bit in that mix.

Meb: But they don’t always, right? Like, the feeling and the assumption that people have got lulled into sleep was that bonds always help. But that’s not something you really can ever count on or guarantee that they’re going to help you when times are bad…

Whitney: No. You know, and I think it all kind of connects to what you were saying before, the volatility this year is really macro volatility that you would normally find in an environment, you know, that wasn’t like the last 40 years dominated by Central Bank, volatility suppression. You know, there’s been this steady stream of monetary accommodation, of spending and asset prices, and so on that’s allowed all assets to rally at the same time. So, for a long time, you had, like, basically, all assets protecting you in the portfolio and you didn’t really need much diversification. But, when you had downside shocks, within that secular environment, your bonds would do well. Problem is now, obviously, we’re not in a world where there can be unconstrained liquidity anymore, and, so, it’s creating this big hole that, you know, is affecting pretty much all assets again together.

Meb: So, you know, one of the things we talked about last time that will be a good jumping-off point today too was this concept of fighting, you know, the last battle. But you talk a lot about, in your great research pieces and spicy Twitter…I’m going to read your quotes because I highlight a lot of your pieces, you said, “Macro volatility is the only thing that matters right now. It’s understandable, given the speed of change, that confusion abounds as folks try to make sense of events using heuristics they developed in an investing environment that no longer exists.” And then you start talking about “risk on cubed.” So, what does all this mean?

Whitney: Yeah, so, I’m talking about this world that I’ve described. So, we have known nothing but for…you know, like for, basically, 40 years actually exactly now, we’ve known nothing but falling rates and tailwinds for all assets and this hyperfinancialization of the global market cap. And that helped, you know, boost everything. So, it’s stocks, it’s bonds, it’s commodities, ultimately, because real spending was also juiced by all of that money and credit flowing around.

And so, that was the secular world that we were in, and that’s sort of the first piece of the risk on cubed. Really, it goes back to 71 when two things happened, you know, under Nixon but semi-independently that created this virtuous cycle that we were in. The first one was, you know, depending from gold and, so, you had, you know, this constraint that had previously applied to lending and cross-border imbalances and fiscal imbalances and debt accumulation. All of that stuff had been constrained, and that was unleashed. And, on the same side, so, you have all this spending and purchasing power from that. You also had the recognition of Taiwan, bringing China in, and, so, you had this, you know, level-set lower global labor costs and the supply of all of the things that we wanted to buy with all of that money. So, that was your sort of secular paradigm. And it was just a fluke that, you know, it ended up being, you know, disinflationary on that just because the supply exploded at the same time as the demand.

Western businesses, particularly multinationals, were extreme beneficiaries of that environment. Right? Lots of, firstly, falling interest costs directly but also huge domestic demand, the ability to take their cost base and put it offshore, all of these things just created a big surge in profits as well. So, profit share of GDP, I’m talking about, like, the U.S., which is the home of, obviously, the most globally dominant companies, profit sharing, GDP is very high. Before last year, their market caps, relative to those record earnings, were very high as well. Wealth as a share of GDP has been exploding during this whole time. So, that’s the first thing. And that encompasses, well, the vast majority of all investors alive today have really only known that period.

Then there’s the second period, which is…so, you have money printing for, you know, basically, to unleash sort of the borrowing potential and fund these deficits. Then, post GFC, everything hit a wall because, it turns out, constantly accumulating more debt backed by rising asset prices isn’t sustainable and people, ultimately, their real incomes are being squeezed onshore, here in the West, you’re taking on all this credit. And so, that hits a wall and you have, really, a global deleveraging pressure. Because this wasn’t just a U.S. bubble, it had, obviously, had an old economy dimension to it as well. And so, everywhere in the world it was deleveraging for a long time.

And so, then you had Central Bank step in with an offsetting reflationary lever, which was the money printing that was plugging that hole created by the credit contractions. So, that was sort of printing to offset, you know, the consequences of the excess spending that had been unleashed by the first risk off. So, that’s two of them.

The third one is post-COVID risk on because there was such an extreme degree of money printing that it outpaced dramatically even a record amount of fiscal spending and fiscal borrowing. So, you had something like, you know, round numbers, the first lockdown cost the economy something like six or seven points of GDP. The fiscal policy offset that by about, cumulatively, 15 points of GDP. And then you had total base-money expansion of about 40% of GDP.

And without going too much into framework, you know, money and credit together create the purchasing power for all financial assets, as well as all nominal spending in the economy. Right? That’s just how things work, because you have to pay for things that you buy, one way or the other. And so, because there was so much money created, and base money typically goes through financial channels rather than sort of, at least in the first order, being broadly distributed across the population, you had things like, you know, massive bubbles in U.S. stocks, which, obviously, had the most aggressive stimulus, both on the fiscal and monetary side, and were the things that people respond to when there’s free money being pumped out by trying to buy the things that have been going up for a long time.

So, these things were already expensive, you know, tech growthy stuff, goods, you know, tech hardware, software, and at the frothier end as well, like crypto and all of that stuff, it all just got this wash of liquidity into it. And so, that was the third one. And that brought what were already very high earnings and very high valuations after a 10-year upswing that really was disinflationary benefiting these long-duration assets. You then pump all the COVID money in on top of that, explains why now we’re having the inversion of risk on cubed. So, we’re going risk off cubed but from some of the highest valuations in history as a starting point.

So, there’s things like maybe just your previous point about heuristics, or, I guess, to wrap it back to that quote, people like to think about, “How much does the market go down in an average bear market?” or, “how much does it go down if it’s a recessionary bear market?” And they just look at these average stats and they’re looking at the market today and saying, “Oh, you know, like, it’s down 30, it’s down 20,” depending where you are, if we’re talking equities. That must mean we’re close to the end. We’re not anywhere near the end of that because, you know, it’s just a different secular environment and the rules that people need to use and frameworks they need to apply to understand what’s driving things are going to look much more like frameworks that worked in the 70s or worked in the 40s during another high-debt high-inflation period. So, there’s analogs people can look at but they’re not within people’s lifetimes, which is what makes it tricky.

Meb: Yeah, you know, there are a lot of places we can jump off here. I think first I was kind of laughing because I was like, “Are we going to be like the old people?” in the decades now we’re like, “you know what, you little whippersnappers, when I was an investor, you know, interest rates only went down and we didn’t have inflation,” on and on. You know, like, we just talked about how good the times were, I feel like the vast majority of people that are managing money currently, you know, you tack 40 years on to just about anyone’s age and there’s not a lot of people that have been doing this, that are still currently doing it that really even remember. I mean, the 70s, you know, or something even just different than just “interest rates down” type of environment. And so…

Whitney: Yeah, I mean, so, I’ll respond to the first thing, you said, “This has been,” yeah, we’re at a really shitty turning point here from extreme levels of prosperity. So, I just want to start this whole conversation by saying, “The levels are very good and the changes are very bad.” And that pretty much applies across the board. Like, the last 20 years, maybe up to 2019, were just the best time ever as a human to be alive. And a lot of it was just technological progress and natural development but a lot of it was this fortuitous cycle of spending and income growth and debt enabling spending even above what you’re earning, even though you’re earning a lot. And this whole world that we’ve known is built on that a little bit.

So, the question is just, “How much retracement is left, economically speaking?” I think the markets are going to do much worse than the economy generally because of that disconnect sort of market caps and cash flows reconverging. But I think that’s the first point to start is the levels of everything are very very strong.

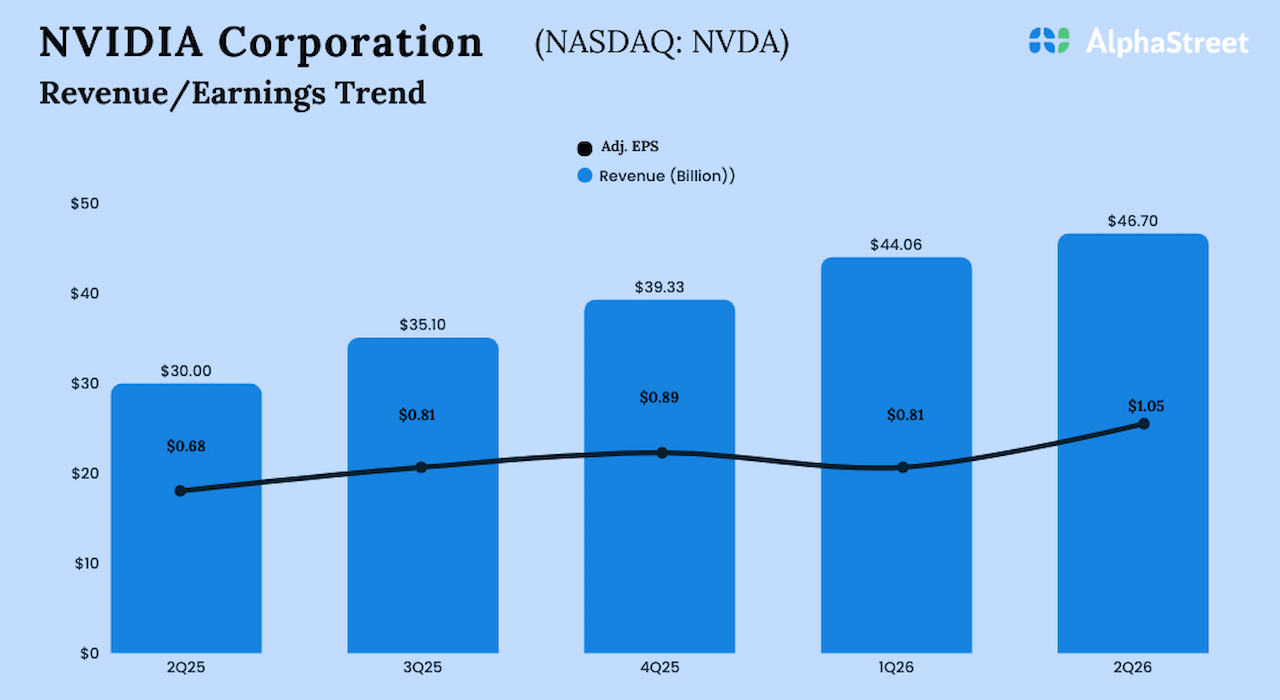

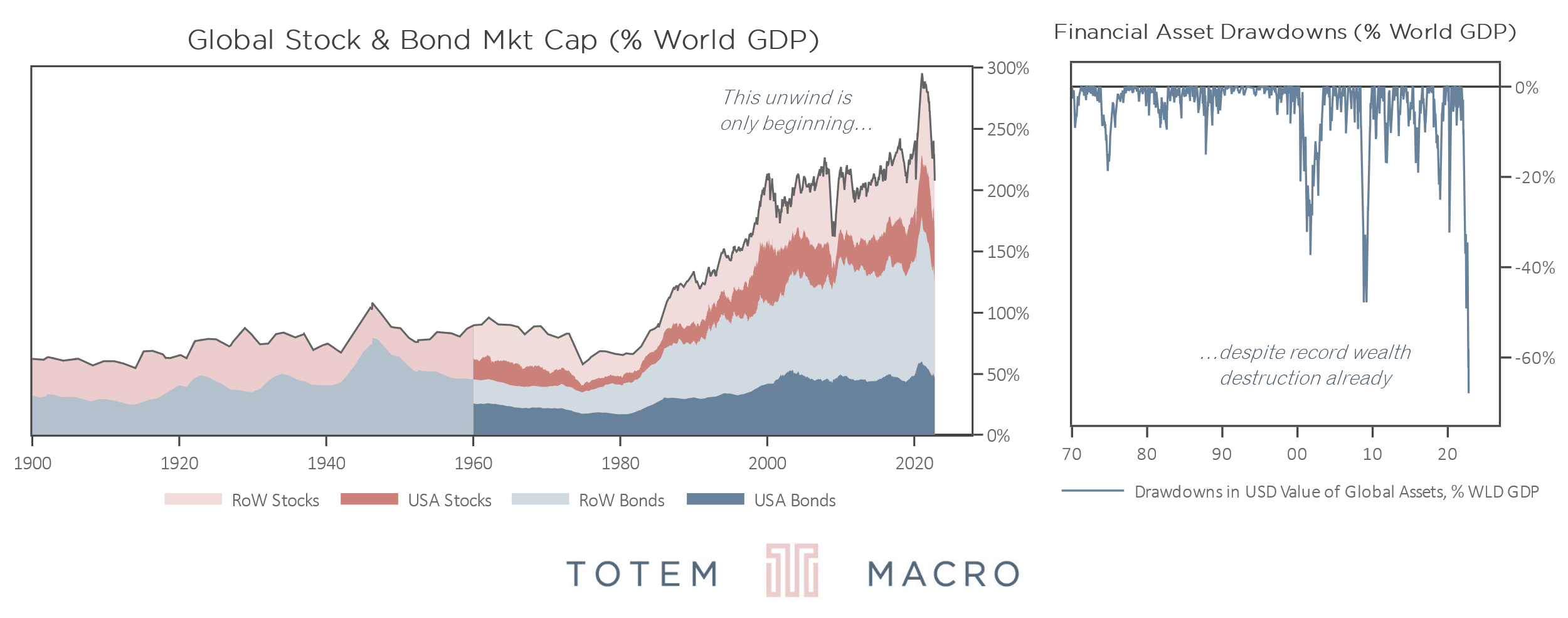

Meb: Yeah. You had a great comment that I think we even briefly talked about in the last show, I don’t want to skip over it because I’m going to try to convince you to let us post your chart, but this concept of wealth, the GDP…did I say that right? Because it’s kind of an astonishing chart when you start to think about a lot of the stuff that correlates when markets are booming or in busts and depressions and they often kind of rhyme. But this one definitely stuck out to me a little bit. Tell us a little bit what I’m talking about…and, please, can we post it to the show note links?

Whitney: Yeah, of course you can. Of course. And I can send you an updated version so you’ve got how much of that has actually come down. Because, obviously, things have moved very rapidly, so…but I guess the sort of punch line on that is we’ve had the biggest destruction of wealth as a share of global GDP ever. So, I think it’s, like, at latest, today’s marks, you know, 60% of global GDP has been destroyed in terms of the asset values. Basically this year, like, during this drawdown. So, it’s a big change but, again, the levels of global wealth as a share of GDP…they’ve been secularly rising but then, with bubbles in between, you know, you see the bubble in the 20s, which was another, you know, techy dollar-exceptionalism U.S.-driven bubble. You saw another bubble like that in the 70s, although, ultimately, that got crushed by the inflation that was going on from the early 70s onwards, which is the analog to today that I think is most appropriate.

A lot of this big shift up in wealth as a share of GDP is a fundamental imbalance between mean the pricing into these assets today and the level of cash flows that those assets are generating underneath. And that gap is extremely high, and it’s only off the highs. And the reason for that is, again, coming back to all of this money that got printed even in excess of what was spent in the real economy, which was so much that it created, you know, very chronic inflation we’re seeing right now on the consumer side of things. But even still there was so much money sloshing around in excess of all of that nominal spending that market caps just got super inflated on top of nominal GDP getting inflated. And so, that’s why we’re at this unsustainable sort of bubble level and why that level is not sustainable. It needs to connect back to the cash flows that service assets.

Meb: Yeah. So, that might be a good lead in the topic du jour certainly in the U.S. today is inflation. And it’s one that’s at a level, tying into our earlier conversation, you know, is something that most investors haven’t dealt with that are investing today. And so, we talked a little bit about it in the last show but kind of how are you thinking about it as one of these macro volatility storms, what’s your current thoughts on it? And this will tie into some of the wealth discussion we were just talking about too…

Whitney: Yeah, there are a lot of there directions I could take that. The first thing I would say, and I imagine we’ll come back to this later, is there are investors alive today who have dealt with inflationary recessions and the constraints, you know, imposed on their policy makers by this unsavory set of trade-offs that we’re now facing. And they’re all in emerging markets, right, they go through this routinely. So, we’ll come back to that point later because there are markets and sort of inflation hedge assets and so on that don’t have these big disconnects.

Meb: It was a great podcast, which we’ll put in the show-note links, that was on EconTalk, that was an entire show about Argentina. But, like, not from a pure economist standpoint but kind of just from a practical, and it was talking about how people, you know, often buy houses in cash and just all these sort of just kind of things you take for granted in many developed economies that it just sounds so crazy…

Whitney: I’m glad you said that because, you know, actually there are two things. When you think about the inflation in emerging markets, they don’t have a lot of debt. Right? The private sector doesn’t have a lot of debt, the government sectors typically run with much less than we’ve got in the developed world. And so, the reason for that is…and two different reasons connect back to inflation. The first one is, when there’s a lot of cash-flow volatility and a lot of macroeconomic effects and rate volatility and so on and they’re kind of used to these big swings in their incomes and swings in…they’re used to having no Fed put in recessions, all that kind of stuff, right? People take on less debt naturally, they just…you know, the opposite of leverage is volatility, and vice versa. And you see that in the markets, right? Volatility creates de-grossing and that’s, like, a clear relationship that exists and it’s why their balance sheets are so healthy.

The second point though connected back to inflation is, even if they did want to borrow, because you go and you look at these countries and, through time, the last 20-30 years, we look at borrowing flows as a share of GDP because it tells you how much spending can be financed, if you look at that, you know, year in, year out, they take out 15-20% of GDP worth of new debt. Which, I mean, the U.S. rivaled that in the subprime, pre-subprime bubble, but that’s pretty high, right? And yet, even with all that high borrowing, that levels just continue to go down relative to GDP.

And that is the power and the lesson of inflation. Which is why, when you come back to sort of the forward implications for the developed world, we’re now running developed-world debt levels on EM-style volatility and the prospect of requiring positive real rates to choke off this inflation problem and yet the balance sheets not being able to handle positive real rates. That’s really the trade-off that’s going to shape how inflation unfolds. And, ultimately, that trade-off really incentivizes policy makers to keep interest rates well below sort of nominal GDP growth or nominal cash-flow growth, you can think about it that way, so that people’s incomes don’t get squeezed and so that, at the same time, the principal value of all this debt that we’ve built up just kind of gets grown into because of inflation. Now, I think that’s just the path of least resistance and that’s why we, ultimately, don’t do what’s required to choke it off, which is a lot, a lot is required to choke it off.

Meb: Do you think the consensus expects that? I feel like, if I had to guess, if I had to guess, I feel like the consensus is that most market participants assume inflation is coming back down to, you know, 2%, 3%, 4%, like, pretty quickly. Would you say that you agree?

Whitney: It’s not even a question of whether I agree, it’s just demonstrably true in market pricing and in survey data and in, basically, the narratives that are discussed on all sorts of forums about, you know, all of the supply-chain normalizations are coming, supply-chain normalizations are happening, inflation is coming down because goods, pricing is coming down or whatever, connecting things and kind of picking these things out of the air and trying to hold on to this idea that there’s a durable inflection because goods pricing is coming down or the things that we were sort of focused on at the beginning of the inflationary problem are now normalizing. But the problem is that, you know, the baton has been passed already to other parts of the economy and other sources of financing. You know, it started out being fiscal and monetary, you know, a lot of base-money expansion, it moved to, “Okay, well, shit, there’s a lot of demand, people are spending a lot. I’m a company, I’m going to hire people and that’s going to, you know, translate into wage inflation and job growth.” And so, now we’ve got this organic income growth that’s very high. And because real rates are so negative, people are borrowing all sorts of money because it just pays to do that. And so, ultimately, we’re getting this acceleration, actually, in total spending power because the private sector is driving it.

So, we’ve already transitioned into a, you know, self-reinforcing inflationary loop. It’s clear to me that the market is not really understanding that because there’s a lot of this focusing on, you know, “Okay, it’s airfares or it’s used cars or it’s,” you know, whatever it might be in that particular month that is the ray of hope. But also I can just look at the bond market, right, the … curve is ridiculous. It certainly gets us down, at this point, to about 2.5 over 10 years, right, so, we’re definitely not pricing. Maybe going from there backwards, we’re definitely not pricing any change in the secular regime. Then, taking a step back, like, four points of disinflation from where we are today is priced in in the next year alone. And yet, at the same time, also just to be clear, there’s not a lot of pricing of a huge demand contraction in the equity market.

So, you know, earnings aren’t priced to fall. There’s a lot of contradictory reads in market pricing and expectations. So, there’s, like, what we’ve refer to as a immaculate disinflation, essentially, priced in. Which is people still think this is a supply problem and so there’s this sort of, like, hanging your hat on the supply things, figuring out all of these, you know, freight rates coming down, all of these challenges, normalizing, and how good that’s going to be and validate market pricing.

My point is, A, it’s not a supply problem, it’s excess demand and it’s a huge level of excess demand that needs to be effectively choked off. But also, even if you did have that, it’s just in the price. Like, that’s what the market is expecting is, basically, resilient fundamentals and, you know, just magical disinflation of about four points in the very near term.

Meb: So, I had a tweet poll, which I love to do on occasion, in June, but I said, “What do you think hits 5% first, CPI or the 2-year?” And, you know, two-thirds of people said CPI. And it’s going to be interesting to see what happens, two years getting closer than CPI. So, is your expectation, do you think that the scenario is that we’re actually going to have interest rates lower than inflation for a little while? I think I may have heard you said that…

Whitney: Yeah, no, I think that’s right. I think so. Yeah, although at higher and higher nominal levels because I don’t think that inflation comes down much. So, maybe, going back to the previous point, this whole immaculate disinflation thing is supposed to happen when the entire time nominal interest rates are below actual inflation. And that’s never happened before for one very simple reason, it’s you actually need the interest burden, the rising cost of servicing debt and so on to squeeze people’s incomes to then generate the spending contraction that chokes off inflation. So, that’s the sequence of events, which is why you need to have, like, X post, you know, positive real rates in order to choke off inflation.

And that’s why, like, when, you know, I think the appropriate framework for thinking about what’s going on right now is an inflationary recession. Which is just one where, you know, you can either have that because you have a supply shock and, so, prices go up and output goes down at the same time or you can have it because, and this is the EM framework, you’re spending a lot more than you make, you’re running hot, you’re importing a lot, inflation’s high, it’s late in the cycle, and so on, you’re very dependent on foreign borrowing portfolio flows, and something changes your ability to get those flows. I mean, naturally, by virtue of them coming in, you become more expensive, or less good of a credit, or, you know, your fundamentals deteriorate, effectively, as the pricing gets more and more rich. So, you’re naturally setting yourself up to have an inflection in those flows. But let’s say there’s a global shock or something externally-driven that pulls them away from you, you have to adjust your current account immediately. You can’t ease into it, there’s fiscal contraction, there’s monetary tightening, there’s a recession, your currency’s collapsing.

Basically, it looks very much like what the UK is experiencing right now. And that’s because the UK started with a huge current account deficit and then it had like a 4% or 5% of GDP energy shock on top of that. And the government in the fiscal budget was going to, basically, go absorb 80% of the cost of that income shock, which meant that people would just keep spending and you’re the UK running, you know, an 8% current account deficit in an environment when global liquidity is, you know, contracting. So, it’s just a classic EM dynamic that we’re dealing with here. And those guys need to engineer very big increases and realize real rates here. It’s not uncommon to see 400-bip, 600-bip, you know, emergency hikes as currencies are collapsing. Because, if they don’t do that, the currency collapse reinforces the inflation. And then you have a domestic inflation spiral and a sort of external inflation spiral that feeds into that.

Meb: I think most people expect the normal times to where, you know, interest rates are going to be above inflation. Is it a bad thing that we may have a period or a prolonged period where interest rates are lower? Or is it sort of necessary, just like, “Take your medicine,” healthy cleansing situation? Or is there just no choice? Like, if we do have this financial repression period, what’s your view on it? Is it, like, something we need or is it just kind of it is what it is?

Whitney: Firstly, it’s really the only choice. Secondly, so, it’s almost something that you need to prepare for anyway because, you know, if you get to the point where we’re running with these debt levels and you actually are seeing interest costs squeeze people’s incomes, at that point, you start to see credit stress. So, you’ll see delinquencies rising and, given the calibration of where balance sheets are in terms of debt levels, that would be, you know, a much bigger deflationary shock than we had in 2008. Which, essentially, you know, enabled us to…we did a little bit of private-sector deleveraging but, in the U.S. at least, mostly by socializing all of that debt onto the government balance sheet while, at the same time, monetizing that. And we got away with it because, you know, there’s a credit crunch and low inflation.

So, that, actually, extended these imbalances. We’ve been accumulating even bigger and bigger imbalances in spending and borrowing and really recently, obviously, asset pricing to such a degree that it’s much more painful now if we engineer positive real rates. Imagine, you know, stocks trading at 20 times earnings…well, earnings is collapsing in real terms or nominal terms…and you’re in an environment of, effectively, the Fed continuing to suck liquidity out of the market, which is just mechanically pull flows back down the risk curve as it were. Like, that’s a world that is very difficult, from a credit perspective, and also very difficult for the government because they also have balance-sheet requirements and they’d also benefit from having their cash-flow growth being t nominal GDP levels which some 2, 3, 4 points above inflation, that’s very helpful. Or, sorry, above interest rates, very helpful for them.

And then, on the flip side of that, asset prices collapse, so, you have a huge wealth shock. So, all of these very nice high levels we’re at just collapse in a really violent way. And then, you know, you get this kind of self-reinforcing deflationary asset decline deleveraging sort of Minsky-style bust. And that’s really the worst way to resolve this because, ultimately, it makes it very hard to get out of it without a…you know, from these levels, this is what EMs do all the time but they can do it because a big debt shock is, like, 10 points of GDP or something. Here, we’re talking about, you know, debt levels in the 300% range, you can’t really tolerate materially-positive real rates.

If I go back and I look at, like, even 2006…and right before COVID, we were just getting there, in 2018. At those points, basically, interest rates had come up and just, like, kissed nominal GDP from below and everything collapsed. And the reason for that…I mean, obviously, there was an unsustainable build-up in debt in the first of those cases, back in, like, pre-GFC, but the reason for that more broadly is that there’s this distribution effect of, “Okay, yes,” you know, “if an economy is growing at 10% nominal, that’s cash-flow growth for the overall economy,” including the government, which tax revenues basically broadly track that, and corporates and labor get some mix. But generally, you know, that is a good proxy for overall cash-flow growth in the economy in nominal terms.

But within that, there’s some people who can actually pass on pricing, you know, cost input pricing and so on. Like, as an example, tech companies are deflationary companies. They by default decrease pricing year in, year out. And if you look at the real guts of the last two and inflation prints, the main things and very few main components that are deflating outright are tech services, internet, tech hardware and goods, men’s pants, for some reason, I don’t know what that is about, also funerals. So, there’s a few things like that. But mainly it is, you know, tech-related and goods-related because people are switching so, you know, quickly into services and the U.S. market cap is so dominated by goods and sort of over represented in the earnings pie.

And so, in any event, there’s this distribution problem where the assets that are the most expensive today are also the ones that aren’t really good, they’re disinflationary assets. Right? They’re what everybody has wanted for 40 years, you know, 10 years, the last 2 years is these deflationary long-duration cash flow profiles, techy secular-growth stuff because the cyclical economy has been so weak. And that’s exactly the stuff you need now but it’s the stuff that people bought the most of and have the most of is, you know, dominating market cap. And so, therefore, at this point, you start to get bigger wealth shocks earlier on, you know, as that gap closes. There’ll be some people who just lose out, as nominal interest rates rise, they just can’t pass through the inflation anyway. And so, if they have debt or their, you know, assets are the ones that are particularly important, you start to see problems in credit stress and a bigger wealth-shocking consequences of that earlier. And even, you know, like I say, back in 2006, the US economy couldn’t handle interest rates above nominal GDP.

Meb: Do you think the Fed or just the people working on this, in their head, do you think they think about asset levels, particularly stocks, and, you know, we were talking about this wealth, the GDP, do you think they secretly or not even secretly want those levels to come down?

Whitney: You mean now that they’ve sold all of their positions, they don’t care anymore?

Meb: The thinking is like, “Okay, look, no inflation’s a problem, we can’t jack the rates up to 10%, or we’re not going to, unwilling to,” and, so, stocks coming down 50% feels potentially palatable because there may be a wealth effect that may start to impact the economy and inflation, is that something you think is possible?

Whitney: Yeah, no, you’re exactly right, I think. There’s basically one real unknown in this whole environment, and that’s the sheer size of the wealth shock. Like we have had wealth shocks before. Obviously, the GFC was a huge housing shock, the dot-com unwind was a pretty big wealth shock, the 70s was terrible. And so, there have been big wealth shocks before but, because we’re starting, again, from such high levels of market cap to GDP or wealth to GDP, we’re having a massive wealth shock relative to GDP.

And so, the question is just…but remember, like two years ago or over the last, really, two years, you had a massive wealth boom relative to GDP. And people didn’t really spend it because they couldn’t, you know, there was the lockdown issues, it just went so much faster than nominal spending in the economy. And so, there was a very small pass-through from that wealth bubble to the real economy. So, that’s the first thing. Or credit flows or anything like that. And now that it’s coming down, my guess is that mostly it just sort of re-converges again with economic cash flows, you get that recoupling. So, there’s is an underperformance driven by the fact that the Fed is now sucking all of that money out of financial markets, so, it’s creating a liquidity hole which is affecting bonds and stocks alike causing a repricing even just in the discount rates that are embedded in stocks but also, obviously, sucking liquidity out of the market in a way that impacts risk premiums and that kind of stuff. And so you’re just getting this big shock there. And my guess is it reconnects with the economy but doesn’t really choke off spending much.

And then, if you go and you look at these cases in the past of big wealth shocks and that sort of stuff, we run these cases of all these different dynamics, because everything going on in the economy can be understood in a sort of phenomenon type way, and, so, if you think about the phenomenon of a wealth shock, usually, when there’s a boom, it’s been driven by a lot of debt accumulation. So, like, the GFC, there was a lot of, you know, mortgage borrowing drove up house prices and it created this virtuous cycle on the upside that then inverted and went backwards. But there was a lot of debt behind that wealth shock, and that’s why there was a big, actually, credit-driven impact on the economy on the debt side of the balance sheet rather than the asset impairment itself being the problem.

Every other wealth unwind, like a big bubble unwind like we had in the 20s…and again, the 20s was like the GFC, a banking crisis, a credit crisis, if you go back to the dot-com, it’s like nominal GDP in the dot-com never contracted, real GDP contracted for one quarter, then it went up, then it went down for one quarter again but like 20 bips. And so, actually, if you look at nominal spending and cash flows overall, even though wealth collapsed in the way that it did nominally, nominal spending didn’t go anywhere except for up. So, you know, my guess is the wealth shock doesn’t do it but it is the wild card because we’ve never seen something so big.

Meb: Yeah, well said. So, a lot of people, talking about the Fed, eye movements, blinking, not blinking, these days we had a fun comment on a podcast recently with Kuppy where he said, “Oil is the world’s central banker now.” What’s your thoughts on…you know, that’s certainly been in the headlines a lot lately, I saw you referencing somebody giving someone else the middle finger. I don’t want to say who it was, so, I want to make sure you get it right, but what’s your thoughts on oil, its impact on inflation, everything going on in the world today?

Whitney: Yeah. So, I guess the place I would start is that, you know, that initial framing of the secular environment, which has been one of globalization where we have become sort of demand centres over here and suppliers of things over here. And no one cared about the security of that arrangement for a while because the U.S., as the dominant power to sort of physically guarantee the security of it, but also financially underwrote it and underwrote every recession, all that kind of stuff. And yet, you know, the sellers of goods, so, your Chinas and your Taiwans and Koreas and your Saudis and so on, this is sort of folding in the petrodollar and oil impacts, all those guys had surpluses from selling us stuff that they could then use to buy treasuries. So, there’s been no period, aside from this year, in the last 50 years when some central bank wasn’t buying U.S. treasuries. So, that I think is one point worth making that reinforces the liquidity hole that we are in broadly.

It’s not that oil prices are low, obviously, it’s mostly that those countries, by virtue of selling us stuff, ultimately, then became more prosperous and started to spend that income on stuff domestically. Obviously, China had a big property and infrastructure boom and so on. And so, by virtue of doing that, they eroded their own surpluses.

You know, if you remember, like, post GFC, the U.S. was really the only central bank that got off the ground interest-rate-wise. Right? So, it was not just U.S. risky assets that dominated inflows but we did have a period where, you know, the world’s reserve currency was also the best carry in the developed world. And so, it sucked in all of these bond inflows and so on. And so, even in the last cycle, when the Fed was buying for a lot of it, even when they weren’t, you had foreign private players like Taiwanese lifers and Japanese banks and so on all buy it as well.

And so, that I think is really the issue on interest rates. And why that matters in terms of oil is, you know, effectively, it was an agreement to supply energy and goods and labor that we need and we’ll supply paper in return. And now that the paper is collapsing, you know, and inflation is high of these prices of supply chain and labor and oil and commodities, it’s not so much an oil thing, it’s just that there’s excess demand across all of these available areas of, you know, potential supply. And so, you’re getting a synchronized move higher in prices and so, you know, this is just another way of saying that the value or the cost of real things is now, essentially, converging with a falling price of all of those paper promises that were made all that time.

And then, you know, post GFC, because of the U.S. getting rates off the ground, a lot of countries, with their diminished surpluses, found that intolerable or, you know, they got squeezed by it if they were pegged to dollars. Saudi and Hong Kong are two of the few countries that remain actually hard pegged to dollars, but China depegged, Russia depegged. You saw a lot of emerging markets one after the other thing, like, “I’m going to get off this thing because it’s choking, you know, my supply of domestic liquidity as well as, you know, making me uncompetitive and, so, worsening my imbalances further.”

And so, you know, we are dependent on those oil surpluses. Have been dependent, I should say. They’re already gone, so, they’re already not really coming back, Saudis not really running much of a surplus. And so, the problem is, even if they did still want to buy the paper and even if they did want to still supply the oil at the prevailing price, they don’t have pegged currencies and they don’t have surpluses, aside from Saudi on the peg, they don’t have material surpluses in any event to use to effectively keep the peg in force and monetize and, you know, buy U.S. treasuries with.

As far as oil itself, I think it’s going back up. I mean, I think it’s pretty clear what’s happened, which is, if you go back to the second quarter of this year, there was geopolitical risk premium, sure, but there was a big dislocation in forward oil and spot oil as a result of the invasion. And you could tell, because of that, there was a lot of speculation going on and there was a physical supply disruption in the spa market. So, for a little bit there, some of the Russian barrels got taken offline, the CBC barrels got taken offline, there’s a little bit of actual disruption to the market. But mostly people just thought there was going to be a lot of disruption and priced it in and then that came out when there wasn’t.

But this whole time…I guess you could maybe justify the SPR releases around that particular time, you know, responding to a legitimate war-driven or, like, event-driven supply disruption but the reality is the SPR releases have been going on since, you know, October-November of, you know, the prior year, if I remember correctly, of last year. So, they were accelerating into this already because there was this incentive to try to keep inflation low. And going back to, you know, beginning of the year, the estimates from, like, International Energy Agency, these types of guys, at the moment, excess demand in the global oil market was something like 600,000 barrels a day. And ever since the Russian invasion, not only is that geopolitical risk premium coming out but they’ve been releasing from the SPR something like an average of 880,000 barrels a day. So, you know, 1.3 times the size of the excess demand gap that we had that was supporting prices in the early part of the year. So, it’s pretty clear to me that, you know, that huge flow is not only going to stop in terms of that selling but they then will, ultimately, have to rebuild and they’re going to do that in forward purchases.

And then, at the same time you got things like the Russian oil ban on crude in December that comes into force in Europe, the ban on product imports, so, refined stuff, which Europe is highly dependent on, that comes into force in February, and so you’re going to see, potentially, more supply disruption around that going forward. Sorry, European sanctions on insurance ensuring oil tankers, they don’t come into effect till December but, you know, it takes about 45 days or 40 days for an oil cargo to actually make it full voyage. So, they’ll start to impact oil pricing or at least, I should say, the availability of insurance and, therefore, the ability for Russia to export oil from, you know, next week onwards, about 10 days from now.

And then there’s the fundamental repricing higher of inflation expectations, and oil is not only a driver of inflation but a very good inflation hedge as an asset. So, there’s a lot of reasons why I think oil fundamentally is being held down by things that are, you know, transitory and, ultimately, that you see a rebound to the sort of natural clearing price. At the same time, like, we haven’t even talked about China, and, you know, it’s a billion and a half people who aren’t really travelling. And so, oil is way up here, even with that potential, you know, sort of, even if it’s incremental, additional source of demand coming into the market still.

Meb: Well, good lead-in. I think EM is part of your forte, so, you just reference China but, as we kind of hop around the world, what are you thinking about emerging markets these days? Never a dull topic. What’s on your mind?

Whitney: So, it’s one of those things that fits into the bucket of people have these heuristics that are based on the old world but also the last cycle in particular. And they think, “Okay, there’s going to be Fed tightening, there’s going to be QE…sorry, QT, so, there’s a liquidity contraction, there’s a strong dollar and so on,” so, it must be the case that emerging markets is going to be the thing that goes down. And particularly the sort of, like, twin debtor, you know, boom/bust, highly volatile, a lot of the commodity type places in Latam and that sort of thing. Particularly talking about those guys rather than places like North Asia that are much more sort of techy and dollar-linked and so on and actually are extremely expensive. So, there’s these huge divergences internally.

But people point to that sort of volatile group and say, “Okay, well, obviously, it’s going to do the worst in a world of rising nominal rates and, you know, contracting Fed liquidity.” And, in fact, even amidst a really strong dollar this year, the, you know, total return on EM yielders is, basically, flat year to date. And partially that’s because the spot currencies have done much much better than the developed-world currencies but a big part of it is that they already compensate you with reasonably high nominal and real interest rates. And those nominal and real interest rates, because they tighten so aggressively and they’re used to being very Orthodox and they remember inflation, right, so, they’re like, “Look, we’re not interested in expanding our fiscal deficit into an inflation problem. We’re not going to do that, we’re going to fiscally contract, we’re going to hike rates, we’re going to do it early,” and they never had the big imbalances or stimulus that, you know, the developed world, effectively, exported to them.

And so, those guys…now, their assets by virtue of having done such a big hiking cycle and coming into this whole thing, you know, almost at their lowest ever valuations anyway then became extremely cheap and already bake in very high positive real rates. So, those disconnects that the developed world will have to deal with don’t exist in a lot of those places.

And, at the same time, their cash flows, they’re oil producers, they’re commodity countries, their natural inflation hedge assets that not just in this environment but if you look, again, at the case studies of all periods of rising and high inflation in the U.S. since the 60s, it’s like oil does the best, nominally, then EM yield or equities, EM/FX, yield or FX, and so on and so forth, it goes all the way down the line, and the thing that always does the worst is U.S. stocks. Because they’re so inherently in the average case, they’re so inherently geared to disinflation and to tech and to, you know, sort of low interest rates and domestic dollar liquidity. You know, that’s particularly the case because we just had this huge bubble and, so, they were not only inflated domestically by everyone domestically buying them but received so many risky inflows in the last 15 years. Like, all of the world’s incremental-risk dollars came into U.S. assets by and large. And so, all of that is flushing out as well.

So, actually, you know, this cycle’s drivers are completely different from last cycle’s drivers. The dependencies are where the flow imbalances have built up is much more centered in the U.S. and in sort of techy disinflationary assets that are linked to the U.S., like North Asia. It was, you know, if you remember, for much of this cycle, it was the U.S. and China together and their big multinational tech companies and, you know, their stocks doing well and so on and their currencies doing well. China, obviously, during COVID, has done terribly and, so, it’s already re-rated a lot lower but already has a bunch of domestic challenges to deal with, right, a huge deleveraging that needs to be handled properly. But then I go and look at the guys in LatAm, you know, Mexico, and Brazil, and Colombia, and Chile, and even Turkey, year to date, have some of the best stock performance in the world, even in dollar terms. So, it’s kind of funny.

Meb: Yeah. Well, you know, emerging markets very much is kind of a grab bag of all sorts of different countries and geographies, and we’ll come back to that. You know, I can’t remember if it was right before or right after we spoke, but I did probably my least popular tweet of the year, which was about U.S. stocks and inflation. There was actually no opinion in this tweet, I just said a few things. I said, you know, “Stock markets historically hate inflation in normal times of, you know, 0% to 4% inflation, average P/E ratio,” and I was talking about the 10-year kind of Shiller, but it doesn’t really matter, it was around 20 or 22, let’s call it low 20s. We’re at 27 now. But anyway, the tweet said, “Above 4% inflation, it’s 13, and above 7% inflation, it’s 10.” At the time, I said we’re at 40. Outside of 21, 22, the highest valuation ever … U.S. market above 5% was 23.

And a reminder, so, we’ve come down from 40 to 27, great, but, outside of this period, the highest it’s ever been in above 5%…so, forget 8% inflation, about 5% was 23. Which, you know, it’s, like, still the highest, not even the average or the median. And so, talking to people…man, it’s fun because you can go back and read all the responses but people, they were angry. And I said, “Look,” not even like a bearish tweet, I just said, “these are the stats.”

Whitney: You know, these are just facts. You know, but it’s interesting, Meb, because it’s like…people, you’re naturally kind of threatening the wealth that they have, you know, in their own accounts because the thing is these assets are the majority of market cap. Like, long-duration disinflationary assets are the majority of market cap. So, you know, people want to believe that. And they’re so accustomed to that being the case too, it’s also like the muscle memory of, “Every, you know, couple hundred bips of hikes that the Fed does proves to be economically intolerable,” and, “I’ve seen this movie before, and inflation’s going to come down.” And there’s a lot of both indexing on the recent sort of deflation or deleveraging as a cycle but also the secular environment. And then there’s just a natural cognitive dissonance that involves the bulk of everybody’s wealth, like, definitionally, when you look at the composition of market cap to GDP or market caps that comprise people’s wealth.

Meb: As we look around the world, so, speaking of EM in particular, there’s a potential two countries that are at odds with each other that are not too far away from each other and make up about half of the traditional market cap of EM, that being China and Taiwan. And you’ve written about this a lot lately, so, tell us what you’re thinking about what’s your thesis when it comes to these two countries. Because, as much as Russia was a big event this year, Russia is a percent of the market cap, it’s small.

Whitney: It was tiny.

Meb: China and Taiwan or not?

Whitney: No, no, totally. And so, this is, like, a big problem for emerging markets, right, which is…you know, firstly, like you said, it’s kind of a grab bag. Like, India’s got A GDP per capita of sub $2,000 and then you’ve got Korea over here at, like, you know, $45,000. There’s this huge range of income levels that comprise that, and, so, there’s naturally going to be different levels of sort of financialization. And then on top of that, which naturally would create market cap imbalances to North Asia, which is, you know, more developed typically, and, obviously, China has had a huge increase in incomes per capita and so on over the last 20 years, so, it’s grown and index inclusion and things like that has meant that it’s grown as a big part of the market cap, but you also had those sort of techy North Asian assets being the ones that were the focus of the bubble of the last cycle. And so, their multiples were also very very high.

So, coming back even to all of the threads that we’re kind of weaving through this whole conversation are similar, which is there’s this group of assets that is very, you know, priced to the same environment continuing and then there’s a group of assets that are priced to a very different environment. Or at least one that faces more headwinds and is priced with extremely cheap valuations that give you a bunch of buffer for the preponderance of idiosyncratic events or supply-chain challenges that persist. Because, like, think about what Russia did to European energy, right, and the whole cost of that and the inflation dependencies that that has created. What Europe was is a supply block that was, effectively, dependent on cheap Russian energy in the same way the U.S. is a demand setter that gets its supply of goods from China mostly, a cheap source of foreign labor. Right?

So, those dependencies exist. And so, if it’s Russia and China as the sort of partnership here in the new…let’s call it the ringleaders of the new sort of Eastern Bloc, the second half of that, the ripping apart of the China-U.S. supply chain and all of the inflationary consequences of that, and not to mention all of the added spending that companies have to do to just re-establish supply chains in more secure places as that whole thing simmers and, ultimately, you get these fractures and these sanctions or the export controls we’re seeing this week and last week. As all these things kind of get ripped apart, the inflationary consequences of that are not really yet being experienced. Right? If anything, China has been a incrementally deflationary influence on the world’s inflation problem, in the sense that Zero-COVID and, you know, weak stimulus up until very recently and the ongoing demand problem in the property bubble, you know, property sector, all of that stuff has made Chinese inflation very low and Chinese spending low and growth weak, and so on.

So, again, that’s another way in which this is the opposite of the last cycle where China stimulus and demand and re-rating and currency were all like up here with the U.S. in terms of leading the charge and actually floated the world economy as the U.S. was dealing with the aftermath of subprime. And now it’s the other way, you know, it’s like that we have all this excess demand, we have all this oil imbalance, all of these things, even though China is operating at a very low level of activity with very low recovery back to something that looks more like a reasonable level of activity. So, you know, it’s just very interesting how the drivers have already changed so much in all these different ways and yet the market pricing is still so unwilling to recognize that those shifts have already happened.

And yet, you know, the pricing is still…Chinese assets have come down certainly but things like Taiwan and Korea and your Korean hardware and all these sorts of frothy sectors that led an EM, that make up a lot of the EM market cap, are very expensive and have yet to price that whole thing in. And, at the same time, like you rightly say, so much of the index is geared to those places that have, you know, these geopolitical divisions between them that will not only, you know, create problems for their asset pricing but create problems for the risk…maybe even the ability to trade them, the risk pricing, the freedom of sort of internationally flowing capital to and from those places. All of these things are conceivable outcomes of a new more challenged geopolitical world order.

And so, if you’re an EM investor, the real problem for you is that there’s a whole lot of really good assets to buy and really cheap stuff and good inflation protection, commodity gearing, and so on, it is largely in, you know, 25% of the index. So, it’s not something that is going to be easy to…you know, when you try to pivot to take advantage of those opportunities, we’re talking about people with assets that are tech-geared, that make up, you know, a huge amount of global GDP, a huge multiple of global GDP. These doors are just very small into LatAm and places like this that have this sort of innate protection. They’re not well represented in passive instruments like, you know, the MSc IEM benchmarked funds and stuff like that, and so, really, it’s going to be kind of difficult to…or you have to just think carefully about how you want to get the exposure.

Then there’s I think the broader question on portfolio construction and geographic exposure in this, you know, balkanizing world environment. Like, you could take one of two positions on that, do you want to keep all your assets in the sort of Western Bloc countries where maybe, you know, you’re not going to be on the receiving end of a lot of sanctions and stuff like but, you know, sort of recognizing that, by doing that, you’re crowding your assets into the things that are least inflation protection, most liquidity-dependent, very expensive, and so on. Or do you want to…recognizing that the breakup of this sort of, you know, unipolar world creates a lot of dispersion, less synchronized growth cycle, less synchronized capital flows, therefore, you know, more benefit of diversification geographically, upswings over here when there’s downswings over here…like, there’s a lot of ways in which actually being more broadly diversified geographically is helpful in a world where, you know, not everything is moving just depending on what the Fed is doing or what U.S. capital flows are doing or, you know, or U.S demand or something like that. So, you know, there’s basically two sides of it but I, you know, grant you that these are huge issues that anybody sort of passively allocated to those sorts of benchmarks has to think about pretty carefully.

Meb: Specifically, I’ve seen you talk about China and Taiwan recently, Taiwan being one of your ideas. Can you give us your broad thesis there?

Whitney: You know, what we’re trying to do, and we’ve talked a lot about this for the last few months, what we generally try to do is come up with sort of absolute return uncorrelated trade views that just are very dependent on the trade alpha itself rather than sort of passive beta. And within that, you know, like I said before, there’s huge divergences within the EM universe, the global macro universe. Like, currency valuations are wildly divergent in real terms, equities, earnings levels, all the fundamentals. So, there are a lot of divergences to actually try to express to monetize, monetize that alpha.

And I think the point about Taiwan is right now we are trying to, essentially, buy things that are extremely distressed but have exploding earnings on the upside and sell things that are last cycles winners, that are pricing this trifecta of sort of last cycles’ bag holders, right, is what we sort of refer to it as. And it’s like the trifecta of peak fundamentals, peak positioning, because everyone has bought your shit for the last 10 years, so, you know, your stock is expensive, your earnings are high, your, you know, tech goods, or your semiconductor company let’s say, coming back to Taiwan. So, your fundamentals are at the peak, your sort of investor positioning and flows have come in and, therefore, that exposure is very high. And also, by virtue of all of those flows and fundamentals, you know, being in an upswing, your valuations are at peak levels.

And Taiwan is really the most extreme example of that trifecta existing in the EM equity space at least. It’s like, if I look at the index, the earnings integer literally doubled in a matter of two quarters. And, you know, to your point before, it’s not a small equity index, it’s not really that small of an economy, but it’s definitely not a small equity index. And the earnings integer went from 13 to 27 because so much of it is tech hardware, obviously semis, but that whole supply chain as well. And so, you know, the explosion in goods demand or in total spending during COVID, then goods demand, particularly within that tech hardware and within that high-precision semis, all of that went in Taiwan’s favor. And at the same time, you had, you know, huge re-rating on top of those earnings.

So, it’s just a great example of…you know, one other principle I like about shorts is to try to have those three conditions met but also, underneath each of them, a bunch of different reasons why they’re not sustainable. Like, “Why are Taiwanese earnings not sustainable? Here’s 10 reasons.” “Why is that level of positioning unsustainable?” and so on. And so, the more ways you can have to be right about any one of those things, the more buffer you have to be wrong on any given one of them. You know, it’s like you don’t need them all to go your way because the thing is priced for perfection and there’s 10 ways that it’s going to go wrong. And that’s just Taiwan.

And then, like, none of this is about the geopolitical risk premium. Right? So, if I’m thinking about the sort of extra juice in that, the geopolitical risk premium is not only helpful as a potential extreme downside event for the short but also which…you know, it’s nice to have some sort of balance sheet or event risk that could, you know, maximize the chances of the thing doing the worst. So, with your, you know, sort of number of factors, you’re like, “All right, how do I maximize my win rate or my probability of success?” and then it’s, “how do I maximize the gains when it does go in my favor?” So, there’s that at the trade level, the geopolitical risk, but also, from a portfolio standpoint, this is a risk that I think is probably the biggest geopolitical risk, I think, by consensus anywhere in the world, you know, outside of the ongoing situation in Russia/Ukraine, which you could argue is sort of a precursor of and potentially, you know, much smaller issue from a market standpoint than, you know, Chinese invasion of Taiwan. So, all assets would be impacted by it to a pretty extreme degree, I think, but none more so in terms of hedging out that risk in your portfolio than Taiwanese stocks. Right? So, it’s just a way to actually add a short position that is extra diversifying to your overall set of risks that you face in the book anyway.

Meb: So, as we look like the UK and around the world, you know, in a piece called “Nothing’s Breaking,” are we starting to see some areas where you think there’s going to be some very real stressors?

Whitney: I think the UK…and I think this is probably purely a coincidence, I can’t think of any fundamental reason why this would be the case, but I think that the UK has been on the leading edge of every adverse policy development that has happened globally in the last 12 years. Like, they were the first ones to do all sorts of, you know, easing measures into the financial crisis. The Brexit was sort of, you know, a preamble of the Trump. Broad advent of populism and populist policies. And then now the fiscal easing into a balance of payments crisis is just very Brazil like 2014. Right? The UK I think is demonstrating what it’s going to be like for countries running huge twin deficits in the environment of contracting global liquidity that, you know, there’s no longer any structural bid for their assets. That’s just the archetype that they’re facing. And it’s a very EM-style archetype.

To me, it’s not really a example of things breaking, it’s just naturally what happens when you have a supply shock of…we had a sort of geopolitical event created a supply shock in that particular area, huge inflation problem in energy and so on, and created this balance of payments pressure. But the thing is that, you know, develop-market governments have gotten used to this ability to kind of…I think I called it like, “Print and eat free lunches.” Like, they just this whole time have been stimulating into everything, have gotten used to all of these policies that they have, spending priorities that they have, not having to trade them off against each other, them not having any consequences, they haven’t really had to respond to an inflationary dynamic amidst a lot of popular dissatisfaction since the 70s. So, again, they’ve forgotten how to do it.

And you see Columbia over here talking about how they’re fiscally tightening by three points. And then the UK, at the same time, currency’s done much worse. I mean, they both haven’t been great but currency has done much worse, obviously. And, you know, they’re sitting here doing a 5% of GDP or trying to do a 5% of GDP fiscal expansion. So, I think that’s just that set of dynamics that are facing developed-market governments and policy makers, those imbalances are what create the moves in yields and asset prices and so on to clear the imbalances.

I think that, in terms of nothing breaking, there’s really two things going on. One is, you know, like, coming back to our previous convo, like, if you think about where we were in, like, September 2019, a very small Fed hiking cycle in an environment of still pretty low inflation and relatively constrained amount of quantitative tightening. You know, and the market couldn’t tolerate. I would argue we were very late cycle in that upswing anyway and, so, you’re naturally setting the scene for a cyclical downswing. But in any event, the point is anyone would’ve thought, going into this year, that 200 or 300 bips of policy tightening would’ve been economically unimaginable, intolerable, whatever. And the reality is credit-card delinquencies, which are always the first to show, they’re at new lows, you know, defaults and bankruptcies are very contained. Any sort of dysfunction in markets is not really showing up.

There was a moment in the worst part of the bond drawdown earlier this year where bid-ask spreads in the treasury market blew out to like 1.2 bips but then they came way back down. None of the emergency liquidity facilities that at Fed are being utilized, there’s no real signs of any stress in the ABS spreads or even CLO losses or even the frothiest tip of credit borrowing in the U.S., which, obviously, is tightening the fastest, totally fine, it’s all going down smooth. Right? The reason is because, coming back to the previous point, that people’s cash flows are growing more than the interest costs and you just don’t see debt squeeze if you don’t either have immediate refinancing needs that don’t get met, like you can’t get rolled, or and that’s just a function of, like, some of the, you know, really frothy long-duration startups and things like that, will be hitting the walls soon because, you know, they were running negative free cash flow, still are in a declining environment, and liquidity has now gone out.

And so, there’s localized issues in those sorts of pockets but, broadly speaking, there’s nothing big enough at the, you know, debt service level to create any sort of systemic problem here, until we start to really get, you know, that gap between nominal cash flow growth and interest rates to a narrower level, such that some people are actually on the wrong side of it. So, that’s on the credit side.

On the liquidity side you have to see a lot more quantitative tightening to just reduce all of the, you know, QE. It both creates reserves on the bank balance sheets but it also mechanically creates deposits as their liabilities to the extent the bonds are purchased from, you know, a non-bank seller. If that’s the case, you know, you got a lot of excess deposits sitting there, people look at cash balances in, like, money market mutual funds and conclude that people are ultra, you know, risk-averse and the positioning is, like, really bearish. But those levels are just high as a function of QE mechanically. And things like the reverse repo facility is still full…I mean, actually, it’s accelerating, it’s got about 1.6 trillion of excess bank liquidity sitting in there. You’ve got a cumulative Fed balance sheet that’s like, you know, many many trillion greater than it was two years ago.

So, all of this liquidity buffer is sitting there accommodating, you know, the trading of assets. All it is is that asset prices are falling, it’s not that the markets are, you know, not working. And so, things, you know, like the pensions crisis in the UK, that’s crazy. I mean, pensions…there cannot be a run on pensions, right? Like, it’s not like you can go to your pension and your defined-benefit pensions, you know, sponsored by an employer in the UK, you can’t go to that fund and withdraw your liabilities. Right? The problem that they had is, ultimately, that they, you know, match their liabilities with a leveraged expression of bond duration, which the UK issues ultra long bonds as a way to help these guys match those liabilities. They got those exposures through derivative exposure so that they could, essentially, post initial margin, take the difference, and use it to buy riskier shit because we are in a world where rates were zero and yields were jerry-rigged lower for, you know, 10 or 12 years or whatever it was.

And so, they were forced to buy all this risky stuff in the same way a lot of nominal return targeting institutions were. And so, all I would’ve had to do is sell the risky stuff and post the collateral. And yes, they’d sell some gilts and yields would’ve gone up, but there’s no way that a 2-trillion-pound guilt market was saved by 5 billion dollars of announced buying and considerably less of actual buying. It doesn’t make any sense. And there’s no way there was actually a systemic risk facing those pensions because, even if their asset pricing went down and became very underfunded, at a certain point, the regulator just steps in, taps the shoulder of their corporate sponsor, and forces them to top up, you know, to regulatory limits. So, it could’ve rippled into some sort of cash call on the sponsors, but that’s not what people were claiming happened.

And so, that’s the kind of narrative that, like…or Credit Suisse, all of that, it was like people are looking for some balance-sheet explosion somewhere and they’re trying to describe falling asset prices by attributing them to a balance-sheet problem when really it’s just money coming out of the system. You know, it was a money-funded bubble, not a debt-funded bubble. And that’s what’s creating the asset drawdowns and it’s kind of just a natural de-risking.

Meb: You had a great tweet the other day that I feel like is pretty non-consensus. I have a whole running list of my non-consensus views, I just remembered a new one today on a Twitter thread. But you have one that says, “The biggest lie in economics is that an ageing population is deflationary. Fundamentally, it’s asset-deflationary and consumption-inflationary.” Can you explain?

Whitney: Yeah. So, I think what people do is they look at Japan and they say, “Oh, yeah, like, we’ve seen how this goes when you have an ageing society which has this sort of declining working-age population ratio, it turns out deflationary.” Right? It’s because like Japan was on the early end of those inflections. And it just so happened actually that that inflection occurred in Japan in 1998 when working-age population started to contract, which was at the same time when the banking system in Japan was finally forced to recognize all of the bad assets and loans that had built up during the boom and Japanese bubble, that, basically, ended in 89.

And so, they were like forbearing all those loans for a while. Actually, the concept of reporting an NPL ratio didn’t exist in Japan until 1998. And when that happened, that was a deflationary debt bust, right? It happened at the same time the population started to contract and, so, people look at the two things…the working-age population…look at the two things together and say, “Okay, well, that’s what happens.” But if you just think about the flows of how it works, it’s like, “Okay, there’s a bunch of people that aren’t going to be supplying their labor anymore,” but they’re still going to be getting income or drawing down their savings, which are invested in assets, typically, they’re drawing that down to fund ongoing spending on things, goods and services, even though they’re not working and producing any income. Right?

So, almost the interesting analogue is COVID. Like, if you go back to COVID, what we did was we paid people a bunch of extra income without having to work. So, they’re sitting there at home, spending, you know, it’s 8% of GDP or whatever extra, they’re spending it on goods and services, they don’t have to actually show up at a job to get the money to spend on those things because the government gave it to them. Well, take that and apply it to the demographics analogue, and the issue there is that it’s not that you’re getting the money from the government, although, in some cases, you will be because there’s pension payouts and stuff like that from the government, but also, by and large, you’re selling down financial assets that you’ve been accumulating for your career, specifically for your retirement. Right? So, that income gap is not plugged by the government, or some portion of it is, but, generally, the most of it is plugged by actually just dissaving your own private pension pot, which is invested in assets. So, you’re selling assets, you’re buying goods, you’re not earning income, you’re not producing goods or services. Like, that’s just how the dynamics work.

And then the only questions really around it are, okay, but then who buys the assets that you’re selling and at what price and then, you know, who do they buy them from and what does that guy do with his spending? Maybe he saves it more? You know, like, every economy is the sequence of, you know, ripple second-order, third-order, fourth-order linkages. But when such a large population inflection is happening and you have already very overheated labor market, you know, the marginal pricing of any incremental supply disruption is going to be that much bigger because you’re already so tight. So, that’s where we are. And then you’re adding this dragon to it.

Meb: As we start to wind down, what has surprised you most this year? I feel like I’m always getting surprised. Negative interest rates would probably be my biggest surprise in my career, I feel like. That was, I feel like, a really weird period.

Whitney: That was a tricky one.

Meb: What about this year? What do you look back on and you’re like, “Huh, that was odd.”

Whitney: The weirdest thing is still happening, which is how long it is taking the market to reprice inflation to derate, you know, frothy stuff. I think it’s weird that, despite so much froth into all this or flows into this frothy stuff, that actually there’s still this buy-the-dip tendency, which is why the market won’t reprice to the new reality. It’s like there haven’t been outflows from private equity, there haven’t been outflows from Tiger Global, there haven’t been outflows from ARK, there’s crypto inflows. So, you know, I look at that and I just say, you know, this has been the longest upswing in, you know, modern U.S. history anyway, and certainly one of the biggest cumulatively in terms of price appreciation was as big as the 1920s but over a longer set of years than, you know, over 25 years, effectively, versus a decade.

And so, the tendency is, like, people just do what they know and they know to buy the dip and they know it’s worked. And so, these flows are not leaving these assets, even though they just keep falling, because there’s no incremental buying. It’s like the assets were dependent on incremental inflows. So, those flows have stopped, foreigners have started selling U.S. stuff but locals have not.

And so, that’s kind of interesting to me. It’s like how strong is that impetus in the market? Because it’s very mechanical when the Fed contracts liquidity, the flows that were pushed out of first, like, the least risky forms of duration that the Fed bought, those flows got pushed into other replacement forms of duration that were more and more illiquid and more and more risky, had less and less cash flows, and so on. And it’s just surprising to me that people still want to buy it and it’s been so slow to reprice. And it’s still that way.

Meb: What’s your guess? And I’ll give you my input, but why do you think that is? This is just Pavlovian where people have just been trained for like a decade, like, every time you dip, it’s going to rip right back up or what?