Episode #459: Louis-Vincent Gave, Gavekal – Investment Themes for 2023

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Guest: Louis-Vincent Gave is the Founding Partner and CEO of GaveKal, a leading independent provider of macro research, and GaveKal Capital, a global asset manager.

Date Recorded: 12/7/2022 | Run-Time: 55:13

Summary: In today’s episode, Louis kicks it off with the biggest topic in global markets today – the Xi Pivot & reopening of China. He shares his outlook for how it may affect global supply chains, commodity markets, and financial markets. He covers the case for the emerging markets, why he isn’t bullish on the US, and why it may be time to rethink your portfolio construction as we head into a new year.

Sponsor: Masterworks is the first platform for buying and selling shares representing an investment in iconic artworks. Build a diversified portfolio of iconic works of art curated by our industry-leading research team. Visit masterworks.com/meb to skip their wait list.

Comments or suggestions? Interested in sponsoring an episode? Email us [email protected]

Links from the Episode:

- 0:39 – Sponsor: Masterworks

- 1:22 – Intro

- 2:18 – Welcome to our guest, Louis-Vincent Gave

- 3:34 – Brief overview of Gavekal Capital

- 4:16 – The state of the global economy

- 6:00 – Implications of recent protests in China and the Xi Pivot

- 13:49 – Increasing attractiveness of emerging markets

- 25:04 – The state of India’s equity markets

- 28:36 – The harsh reality of US debt markets

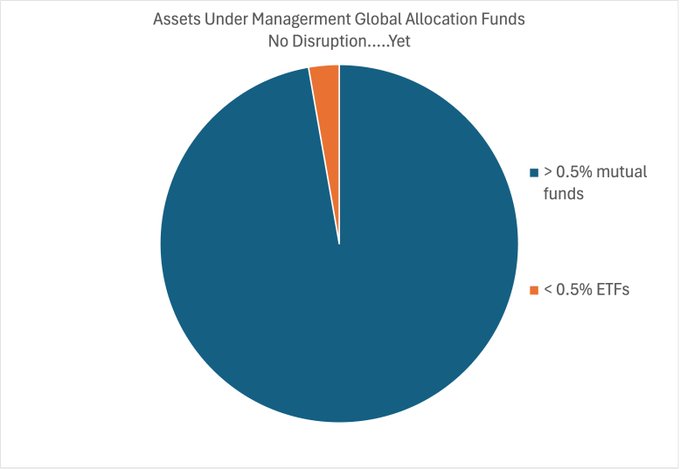

- 32:52 – Gavekal research piece with chart referenced

- 35:57 – Parallels to Japan’s economic bubble and fallout in the 1980s

- 38:42 – Broad allocation strategies for today’s inflationary environment

- 43:15 – A view he holds that a vast majority of his peers do not

- 45:32 – Eye-opening implications of inflation around the world and across time; Planet Money: Messi Economics

- 46:24 – The Stay Rich Portfolio; Meb’s poll on safe money

- 47:40 – His most memorable investment or position

- 51:52 – Learn more about Louis; gavekal.com

Transcript:

Welcome Message: Welcome to “The Meb Faber Show” where the focus is on helping you grow and preserve your wealth. Join us as we discuss the craft of investing and uncover new and profitable ideas, all to help you grow wealthier and wiser. Better investing starts here.

Disclaimer: Meb Faber is the co-founder and chief investment officer at Cambria Investment Management. Due to industry regulations, he will not discuss any of Cambria’s funds on this podcast. All opinions expressed by podcast participants are solely their own opinions and do not reflect the opinion of Cambria Investment Management or its affiliates. For more information, visit cambriainvestments.com.

Sponsor Message: Goldman Sachs recently said the days of Tina there is no alternative are over. In fact, 88% of advisors surveyed by RIA Intel contend to increase portfolio allocation to alternatives over the next two years. I’m invested in alternatives myself, including with Masterworks a platform for investing in fine art. The last time inflation was this high from 1977 to 82. The art 100 index appreciated 130% versus 80% inflation, so check out Masterworks they’ve sold five paintings this year, one as recently as last month. I’ve been investing with them for years myself, and they’ve even had the CEO on the podcast. Sometimes paintings on Masterworks have even sold out in minutes, but you can get special access at masterworks.com/meb. That’s masterworks.com/meb see important Regulation A disclosures @masterworks.com/CD. Last time masterworks.com/meb.

Meb: Welcome podcast friends we got a great show as we wind down 2022. Our guest is Louis-Vincent Gave founding partner and CEO of Gavekal, a leading independent provider of macro research in Gavekal Capital a global asset manager. In today’s episode, Louis kicks it off with the biggest topic in global markets today, the chief pivot and reopening of China. He shares his outlook for how it may affect global supply chains, commodity markets, financial markets, he covers the case for emerging markets, why he isn’t bullish on the U.S., and why it may be time to rethink your portfolio construction as we head into a new year. Please enjoy this episode with Gavekal’s Louis-Vincent Gave. Louis, welcome to the show.

Louis-Vincent: Thank you very much. Thanks for having me. Good to meet you.

Meb: Where do we find you today?

Louis-Vincent: I’m on Vancouver Island. About 30 minutes north of Victoria.

Meb: I got to see your view out the window. I’m also looking out the window here is a beautiful SoCal day. It’s a little Pacific Northwesty you mentioned you’re a little bit interior, not Victoria waters a little colder. Where are you?

Louis-Vincent: Yeah, I’m on a place called Cobble Hill, right on the water as well. So we’re looking, I guess at the same ocean, but you’re probably right. It’s not exactly the same weather it’s dark and gray. Actually, I own a property that used to be owned 100 years ago by Al Capone. He used to run his whiskey from here because we’re right across from the San Juan Islands. So he would load up some small ships and bring whiskey over to the San Juan Islands that are obviously U.S. owned and put the whiskey on to bigger boats that would then go down to LA and San Francisco. I’m basically in the Bahamas of the days.

Meb: You find any Capone artifacts, any bottles of whiskey in the basement?

Louis-Vincent: No, I was hoping. No old guns, no bottles of whiskey, no hidden stashes of money. Nothing at all, no, been very disappointing. We should have had Ronaldo come and open the basement, but no, nothing like that.

Meb: So you spent a pretty good amount of time in Hong Kong as well. A lot of the team there. How do you kind of divvy up the travel these days?

Louis-Vincent: So our firm is based in Hong Kong, and I spend most of my career there. I’ve lived in Hong Kong more than I’ve lived anywhere in my life. As you point out Gavekal my company is headquartered in Hong Kong, we have an office in Beijing, we have an office in Singapore. So we’re primarily an Asian firm. Before COVID. I was sort of doing half and half obviously, during COVID. That was impossible. I did go back a few times and dealt with the quarantine and everything else. But since then, I’ve basically been mostly here. I’m starting to go back and forth again. I was just back in Hong Kong for three weeks. Just got back. And now I’m here.

Meb: All right. So I’ve been a long-time listener anytime I see you come across my podcast feed or get lucky to read one of your research reports, I jump at it. And I’ve always been a big fan. You certainly have a view that’s global, most U.S. investors, and this is institutions too they love to have the home country bias, as does everyone really, but you have a global perspective. So we’re going to talk about a lot today. And I’m going to let you choose where we begin, whether it’s U.S. or whether it’s China. We’re recording this mid-beginning of December 2022. What’s the world look like as we finish this year?

Louis-Vincent: I think the big story is China’s reopening, right? You have the second-largest economy in the world that’s been kept mothballed for three years. Now it’s reopening. And I think that begs a ton of questions. It’s how much pent-up demand is there going to be? How much supply chain dislocations are we going to face? What does the reopening of China tell us for the near-term political health of the country? I mean, there are so many different rabbit holes, we can go down. But for me, that’s the big change. And it’s all the more important change since we know that the U.S. economy is slowing down. If you look at most leading indicators, whether your ISM surveys, your yield curves, your OECD leading indicators, they’re all pointing to some kind of slowdown, same story in Europe, probably worse in Europe. Actually. We also know that each time Chinese growth has really accelerated in 2003, in 2008, in 2015, it sort of triggered a rebound in the global industrial cycle, China reopening is going to lead to a rebound. The question is how much, and is it going to be big enough to trigger a global rebound? That for me is a big question. So I think bottom line, we should start with China.

Meb: All right, so I think a lot of listeners investors say, Okay, well, we’ve seen this play before China looks like they’re going to start to reopen and they don’t they shut everything down. One of the different things seems to be an indicator of this last grouping has been the protests, is that something from a Western media perspective is legit and real? And is this causing a real pivot. Or is it something that, you know, is just going to get smashed down and go back to lockdowns?

Louis-Vincent: No, I think it is causing a real pivot. And here, that’s perhaps where there’s divergence between the western view of China and the reality on the ground. Most people in the Western world probably don’t realize this. But there are protests all the time in China. They’re not covered by CNN or CNBC or anybody, because the protests are typically about local issues, polluted water, or corrupt officials, or whatever else. So you have a sort of roadmap as to how the Chinese government deals with protests. And the roadmap is they give in as quickly as possible, what they do is they blame middle management. So they’ll fire the local mayor, fire the party official, and then they give in and they give in because fundamentally, the Chinese Communist Party owes its legitimacy from its ability to keep social stability.

Now, I know in the Western world, the view is, the Chinese Communist Party owes its legitimacy to its ability to deliver the economic goodies to deliver growth. But that’s actually not true. What the Chinese Communist Party prides itself on is maintaining social harmony, peace, etc. Partly because if you look at China’s own history, from basically 1850, till 1975, it was nothing but anarchy, hyperinflation, famines, foreign invasion, Civil War, it was the most miserable place to live for 125 years. So the bottom line there’s a huge premium to social stability in China massive premium. And I know that in the Western world, when we think Chinese protests, our minds immediately hark back to 1989, right, because those were very powerful images, the guy blocking the tanks the students getting shut down. These are powerful images.

So in our minds, we see this, when the protests broke out a couple of weeks ago, everybody thought, oh, my God there’s going to be another Tiananmen, they’re going to send the troops, they’re going to shoot down everybody in the streets. It’s going to be horrible. Not at all. Instead, what we’re seeing is, they’ve turned around, and they’re rapidly reopening, you had an editorial in the Beijing times last week highlighting that, look, when we shut down, it was the right thing to do, because COVID was very deadly, but COVID isn’t very deadly anymore. We’ve had now 5000 cases a day in Beijing for the past week, we’ve had zero deaths. So we can reopen COVID is no longer deadly. And that is now basically, the message being pushed out there.

And the only question now is how fast is the reopening going to happen. And what are the consequences? Now the good news is we sort of have a playbook. We’ve seen reopenings. In the U.S., we’ve seen reopenings in Europe, we’ve seen reopenings in Australia, and Brazil, wherever else. And you’ve sort of always seen the same thing, massive pent-up demand, but at the same time, and for me, that’s the big question is when you first reopen, everybody catches COVID. And it doesn’t mean you die, because actually, the death rate is really low. But everybody calls in sick. Do you remember a couple summers ago, when the U.S. reopened? It was the summer of the canceled flights. All the flights were canceled because the pilots were calling in sick because the stewardesses were calling in sick, do you remember you live in LA, you had like 100 ships waiting outside of LA because the dockers were calling in sick the truckers were calling in sick. You had massive supply chain dislocations everywhere, simply because people wouldn’t show up to work for two weeks. China’s now going to experience this. You have to imagine that the virus is going to run through the country, partly because that’s what the virus does. Partly because China is a very, very densely populated country.

The landmass of China is roughly the same as the U.S. but it’s four times the population and it’s like everybody lives along the east coast. So it’s super, super densely populated. So bottom line, I think if your business model, let’s say your Apple, and your business model is dependent on having 100,000 workers show up and live in dorms on top of each other, you’re going to have a tough three to six months, because those guys are going to be sick.

Meb: Yeah. So your best guess as you look to this, and culturally speaking, accounting for the differences is this something that you feel like China has really planned for? They’re like, all right, we’re going to stock up on materials. We know that this is coming at some point we’re going to prepare for this or is this something that’s just going to be a massive surge in consumer demand that overwhelms everything? Like, what’s the kind of implications that you think as far as markets and economies this is really going to have?

Louis-Vincent: I wish I knew. I wish I knew. I do think China was in the path of reopening, you saw Hong Kong already reopened, they already reduced the amount of quarantine to come into China. So it was on this path already. So I think that there was some level of planning. I do believe the demonstrations have brought everything forward and at an accelerated pace, but they were going in that direction anyway. Now, have they stockpiled commodities? Yes, I believe they have. Because if you look at the data, for me, one of the more interesting data points that nobody talks about is pre-COVID, China was importing 4 billion a month worth of commodities from Russia, every month, post-COVID. These past few months, China was importing 11 billion. So almost three times as much. You would look at this and you think, how’s this happening when there’s no construction going on? When the real estate markets been tanking? When obviously, everybody’s stuck at home. It has to be stockpiling.

And in that regards, it’s interesting that as China reopens I along with a lot of people expected energy prices to rally hard. It’s like China’s consuming a million and a half barrels less than it otherwise would. But it’s not happening. So on the commodities front, I think that they have stockpiled. But here’s the other question. In the U.S. when people came out of lockdowns, they found out that mortgage rates were 100 basis point below where they were when they’d gone into lockdown. They found out that for the same monthly car payment, instead of getting a Toyota, you could get a BMW or you could get a second car. And everybody did that. It’s like, oh, for the same monthly payments, I can get 50% more house, oh, I’ll upgrade my house. And then everything that goes along with it, I need to buy a new fridge, I need to buy a new oven, then you find out like supply chain dislocations all over the shop. I highlight this because while everywhere in the world mortgage rates have just gone up 200, 300, 400 basis points in China in the past 12 months have gone down 150 basis points.

So now people are going to come out of lockdown. And they’re going to find out that oh, my car payment is so much cheaper. I can afford two cars instead of one. Or I can afford 50% more apartment. So the big question is, are they going to do that? Because, yes, they might have stockpiled commodities, but they didn’t stockpile Toyota cars. They didn’t stockpile ovens and fridges. Nobody does that. So if at the same time, the Toyota factory in China, or the Honda factory in China doesn’t get delivered gearbox because the guys at the gearbox factory all have COVID, then of course, you can’t deliver a car. If you have a car without a gearbox, you have a paperweight. And so I think the potential for supply chain dislocation on the consumer goods side is quite high. In essence, why should we expect China to have a different experience than what we had? That’d be my question. When I say we, I mean, France or the U.S. or most of the western world, I think as China reopens, you’re going to get the increase in demand on the one side, and the supply chain dislocations on the other. So it’s going to be potentially the last COVID-linked inflationary shock to the system.

Meb: And so as we started to think about China and assets in a portfolio, we tweet a lot about emerging markets. But China in particular being the elephant of emerging markets, you know, the average U.S. investor, if you look at I think global market cap emerging markets is let’s call it 13% ish depends on if you do float-adjusted or whatever, but the average American has about 2%. I think Goldman says in emerging markets, so way underweight in general, but China and particularly on the equity side, if you look at the valuations, it’s either at or near the cheapest it’s ever been going back 30 plus years the market going down 60% has a way of causing that to happen, of course, who are the winners and losers? As we look out Chinese stocks, they look good to you they risky, as we look around the implications of this, what’s the impact?

Louis-Vincent: I’d add one more thing. Two months ago, I was doing call after call with clients who were asking, Is China uninvestable, which is of course what you ask before it falls 60%. So I think there’s been like, everybody’s puked out China and there was a sort of cathartic moment with the people’s Congress when they took out Hu Jintao and very publicly humiliated him and Xi Jinping basically monopolized all political power. Everybody decided all right I’m out. For me. That was the final puke. And since then it’s been good news after good news. But you know the luck. The bottom line is China’s reopening. How do you play that you buy China, I mean, let’s not beat around the bush. It’s undervalued, it’s under-owned, and you have a positive catalyst for growth, positive catalysts for earnings. And it has started to outperform. The beauty is it’s a liquid market, it’s decently big. There’s some fast-growing names in there. So that’s the obvious play. But to your point, China, it’s the second biggest economy in the world. And it’s the primary source of growth for most emerging markets. You look at the Indonesias the Thailands, the Saudi Arabias of this world, their growth are increasingly tied to what’s happening in China.

And so the fact that China is now rebounding is going to be a great boon for all these guys. Now, it’s also a very important market for Japan and for Europe, if you’re very reluctant to take risk, and you think, I can’t trust emerging market accounting, or this or that you can play through Japan or through Europe, I’ll just highlight one thing if we’d had this chat a year ago. And if I told you look over the coming year, you’re going to see the Fed be much more hawkish than anybody expects. They’re going to raise rates, 400 basis points, or 375. But whatever, while the markets expecting 150, so much more hawkish than anybody expects, number one, number two, the U.S. dollar, as a result is going to rebound very strongly, the DXY is going to go up 22% in six months, which it’s basically only done once before. And number three, China’s going to stay on lockdown, and a much harder lockdown than anybody expects for the next 12 months. If we thought that a year ago, we would have said, “Oh, my God, just avoid emerging markets. It’s going to be a bloodbath,” right? Tied to Fed, strong U.S. dollar, weak China. That was like a recipe for a massive faceplant.

Now, interestingly, in the past year, you look at whether on the bond side or the equity side markets like Indonesia, Brazil, South Africa, Mexico, India, they’ve all outperformed the U.S. bond and equity markets in spades. This is highly unusual, because emerging markets in general, they tend to be the redhead stepchildren of financial markets. When things go bad, they’re the first ones to get slapped. In Asia, where I’ve spent most of my career, you take a market like Indonesia, Indonesia is your typical market, you avoid each time there’s a sell-off, it always gets sold hard. And yet this year Indonesian bonds, you barely lose any money on them. And you actually make money on Indonesian equities. I highlight this because for me bear markets as unpleasant as they are out there for a reason. They’re there to transfer the leadership of one group of stock to the next. We’re in the midst of a bear market. It’s not fun. Nobody enjoys it. But while you’re in a bear market, what you need to do is try to look for where are you seeing outperformance? And today, one of the places you’re seeing clear outperformance in spite of massive macro headwinds is emerging markets.

Now, let’s fast forward to the coming year. What are going to be the trends next year? Number one, by far the biggest trend, China reopens massive, very important trend. Number two, I think there’s a good chance the Fed is basically done rising pretty soon, they might have one more rate hike and then maybe two, but that’s roughly it. Number three, the U.S. dollar has already started to roll over, identifying that the Fed is getting close to done, the U.S. dollar is rolling over. So those huge three headwinds to emerging markets are now turning into tailwinds because when the U.S. dollar is weak, that’s good for emerging markets. When the Fed doesn’t tighten, it’s good for emerging markets. And when China is booming, that’s good for emerging markets, emerging markets outperformed when they should have underperformed. So what are they going to do now? I think it’s the place to be emerging markets, the markets right now, if you just listen to them, it’s telling you this is the new bull markets. This is where you need to deploy capital. And to your point, everybody’s looking at it and be like, no, I’m not doing this. And Americans have like you point out 2% of their assets in emerging markets. So they’re going to miss that whole first massive leg in the bull market.

Meb: One last thing on emerging markets that I think is probably one of the reasons particularly the big institutions had a big pause, and individuals too was the entire Russian securities market becoming essentially paused or uninvestable. Russia is largely a rounding error compared to China, as far as size with these investing markets, even though like 95% of emerging market funds own Russian stocks, they look and say, wait a minute, this is a possible playbook for China, Taiwan. It’s hard to ever come up with odds but is that something that should be a serious concern from the investor standpoint is it likely unlikely consensus non-consensus what do you got?

Louis-Vincent: It should but perhaps not for the reason you think. So first, I don’t believe for a second China’s going to invade Taiwan. They can’t pull it off, mounting an amphibious operation of 100 miles of sea. Hitler when he controlled the whole of Europe didn’t even try to invade Britain, and that was just six miles of sea. Mounting and figures, operations is the hardest thing in military and Taiwan is a chain of mountains that fall into the sea. And when you look at the struggles that Russia is having to invade Ukraine, and that’s just sending tanks over fields of wheat, then forget that it’s like Taiwan isn’t going to happen. But the question is, nonetheless important, because it highlights the underlying theme of the day, which is deglobalization. When most people think of deglobalization. They think of the Apple supply chain or the Nike supply chain, and whether that moves back towards the U.S. The much more important deglobalization is the deglobalization of financial flows, the fact that Russians obviously can’t invest in anywhere, but Russia now.

And if you are a European investor, if you’re a U.S. investor, all of a sudden, you think, oh, maybe China is a dangerous place for me to deploy capital. But that knife cuts both ways. If you’re Chinese, and you look at this Russian invasion, if you’ve been a rich guy in China, for the past 20 years, each time you made money, you bought a house in Vancouver, or a house in Sydney, or a house in London, you redeployed capital in the Western world, because the greatest comparative advantage of the western world is the rule of law. Its property rights, it’s the fact that if I have a problem whether I’m black, brown, yellow, whether I’m Jewish, Muslim, Christian, Hindu, I go in front of a court of law, in Vancouver, in London, in New York, and I’m treated equally next to the next guy, right? It’s all flat. Except we’ve just added a little asterisk to this. We’ve said except if you’re Russian. If you’re Russian we can take all your stuff, we can take your football club, we can take your house in Saint Tropez, we can take your yachts, we can take your private jets, we can take your house in South Kensington. And we can do this without any court orders. Without any discussion in Parliament. We basically have the G7 world leaders get together over a weekend and they decide to do this.

Now, if you’re Chinese, you see this, you think, okay, except if you’re Russian today, it could be except if you’re Chinese tomorrow, this house in Vancouver that I bought on the premise that it was a safe house if in case things went wrong in China I could always move to Vancouver. Well, actually, this house isn’t what I think it was it is because if things do go bad, then it can get confiscated. And so following this Russian invasion, I think we’ve undermined the biggest when I say we I mean the Western world, our biggest comparative advantage, the rule of law and the sanctity of property rights, we’ve torn that up. I don’t think we realize it. When you live in the Western world, you don’t realize we’ve just done that. But from an emerging market, where you’re very attuned to these things. Because you’re always worried that the government is going to come and take your stuff. If you’re rich in China, if you’re rich in Saudi Arabia, you’re worried the government’s going to come and take your stuff. Look at what happened to the Saudi princes, when MBS got to power, right, they all got to be holed up in the Ritz Carlton and basically for a shakedown.

So when you come from an emerging market, always worried about this, and the Western world was always the place where you deploy capital. If you were Chinese, and you bought houses in Australia, or the UK, you didn’t do it because you thought this would have good returns, you did it for the safety of the capital, forget the returns, you didn’t care about the return on capital, you cared about the safety of capital. So we undermine that. And since we’ve undermined that, what’s happened, our bond markets have collapsed, bond yields have gone through the roof property is going down. And here you get to the crux of the matter, which is why I thought this deglobalization matters a lot more than people think, but perhaps for the wrong reasons. They’ve got it backwards. You take a country like the U.S., you take a country like my own France, you take the UK, these are countries that have run for 20 years, massive twin deficits, big trade deficits on the one hand, big budget deficits on the other, you need somebody to fund that. And the way we funded that was by selling assets to foreigners.

The biggest assets we sold were one government bonds and two real estates. And we sold it to the countries that had constant current account surpluses. The Saudi Arabias of this world, the Burhans the Qatars the Chinas the Bruneis, if you look around the world, most western democracies have big twin deficits. Most emerging markets have big twin surpluses. So we’ve lived in this odd world where poor countries are funding rich countries, and they were doing so because of the security of capital. Now, if you’re China, you think if you’re Chinese, I don’t want to buy any more Vancouver real estate. I don’t want to buy any more London or LA real estate. Now what you’re going to do is you’re going to buy your real estate in Singapore, you’re going to buy it in Dubai, which are really miniscule markets. So it’s going to be a lot of money going into a very, very small place. And for me, this deglobalization of finance is perhaps one of the explanations why emerging markets have outperformed this year when really they shouldn’t have is the savings are no longer going to flow from emerging markets to developed markets. They’re going to stay in emerging markets, begging the question of, okay, how is the U.S. going to fund twin deficits worth 7%, 8%, 9% percent of GDP. How is the UK going to do that? The answer is that they won’t. And so the currencies will have to fall.

Meb: So other than shorting Vancouver real estate, I heard you guys mention, India has been having a nice run of it lately in their equity market. They’re one of the most expensive markets that we track, most of the countries around the world we think are pretty reasonable too cheap to screaming cheap, the U.S. is not in that bucket, we think they’re still pretty expensive market cap weighted, but what story with India? Are they going to be a beneficiary or are they going to get hurt by the China reopening?

Louis-Vincent: I think in the short term, they get hurt. So first, look, India is always expensive. It’s been expensive, pretty much my entire career. It’s expensive, because it’s an exciting story, it’s an exciting story of a rising middle class of pretty good track record of local entrepreneurs and using capital relative to a lot of emerging markets, it’s got a lot going for it. Now, the one great new advantage for India is, in every cycle India, whenever oil prices rose too much, they would get crushed because they have to import so much of their energy. And so they’d have a deterioration in their current account balances, which would force the central banks to tighten, and you’d enter a bear market, something new is happening in India, in that they’re getting to pay for more and more of their energy in their own currency. They’re buying their oil from not only Russia but also Iran in Indian rupees. So that basically relieves a sort of Damocles sword from over their head or at least a sort of current account constraint that was always there. Having said that, I think one of the reason India’s done quite well, is that if you’re an EM manager, or if you’re a Pan Asian manager, it’s been the only good story this year, that and to some extent, Brazil, but you have some political uncertainty in Brazil.

So if you’re an EM manager, and you have to go pitch your clients, and you can’t say, well, where are you invested? You want to say India, because then you don’t get nasty questions. If you say, Oh, I’m overweight China, you get all sorts of nasty questions. Oh, but aren’t you worried about Taiwan being invaded, money being frozen, etc, etc. So, the way perhaps, you know, that swing games that kids have where one goes up, the other goes down, and it swings like this, to me, this is how China and India are, when foreign investors decide, can’t be in China, for whatever reason, the money all goes to India, all the EM money, but then when China rebounds, the money has to come from somewhere. And initially, it comes from India. So as you look at China reopening, I think the first adjustment will be every emerging market fund, every Pan Asian fund will have to sell India and buy China. So in the near term, China’s reopening is not great news for India. But I think once you pass that phase of portfolio readjustments which will probably take six to nine months, then India is fine, just like it’s not going to be a great six to nine months that’s it.

Meb: This episode is brought to you by Cambria, a global asset manager, unhappy with your portfolio’s performance this year with one of the worst starts ever for traditional U.S. stocks and bonds. Is there a better way? Cambria thinks so. Cambria provides investors with global market exposure and low costs differentiated quantitative-driven strategies like deep value and trend following. Join over 100,000 current Cambria investors today to learn more, email us at the following address [email protected]. Or if you’re a financial professional, check out the contact us page on our website and reach out to your local representative today. Investing involves risk including possible loss of capital past performance is not indicative of future results.

Let’s talk a little bit about the U.S. which I’ve heard you describe as for the better part of a while the cleanest dirtiest shirt, which is like my theme for the pandemic I feel like of my wardrobe. What does that mean, when we’re talking about the U.S. economy? I mean, the U.S. dollar is just romping and stopping the U.S. stock market has been the only place to be for a better part of a decade. Is that coming to an end? What do you see?

Louis-Vincent: I think it’s already come to an end. And I think it was Bruce Kovner of Caxton who said where he’s made the most money in his career is when everybody he talks to was telling him one thing, but the market was already telling him something else. And today to your point, the general perception out there partly because of the U.S. dollar strength is that the U.S. is the cleanest dirty shirt. It’s the only thing that can be seen in. Everything else, Europe has got potential energy crisis. China is uninvestable. By default, you’re left with the U.S. So the general perception is the U.S. is the place to be but meanwhile, when you look at the performance of markets again, you know you’ve made money in Brazil this year. You’ve made money in India, you’ve made money in Mexico, you’ve made money in Indonesia, there’s so many big markets that did fine. So the market is… everybody tells you oh U.S. is the cleanest dirty shirt. And meanwhile, it’s like well hold on stock market that’s down 20%. And the bond market that’s down 20% does not qualify as a clean, dirty shirt, it’s just a plain dirty shirt. It’s just dirty, and you shouldn’t be seen in it.

So the bottom line for me is, if you project yourself to the coming year, what’s going to be the big story, one is China reopening. So we’ve covered that. I think the second story for 2023 will be a lot of U.S. bankruptcies, during the years of easy money, you had a lot of stupid projects that got funded, and companies that are still to this day burning through cash. Now, the reality is, if by now you’re not in a positive cash flow as a business, if you’re not in positive cash flow when you’ve just had quite a few quarters of basically double-digit nominal GDP growth, plus 0% interest rates, if you can’t make money in that environment, that means you’re never going to make money. And in the coming year, investors are going to let you go. So you’re going to see a lot of bankruptcies in the U.S., you’re going to get into a bankruptcy cycle, which will mean wider corporate spreads.

And here for me, that’s if you want to be scared about something, for me, the story is pretty simple. In 2007, 2008, you had roughly 600 billion of triple B debt in the U.S., today, you have about 4 trillion of triple B debt. In the U.S., when you get to a recession, anywhere from a fifth to a quarter of that triple B debt typically gets derated to non-investment grade, now the non-investment grade market in the U.S., is around a trillion dollars. If you think that in the coming year through bankruptcies, you’re going to get another trillion added to that, it’s like who’s going to buy this because dead markets are extremely binary, if you’re managing an investment grade fund, if something gets downgraded to non-investment grade, you can no longer hold it. Now historically, what you would do is you would call your friendly broker at Goldman Sachs or your friendly broker at Morgan Stanley, and you say, hey, I need to get rid of this on my book, can you guys take this from me, and you know, Goldman would bid you I don’t know, 55 cents on the dollar. And you’d shout at your broker, but you’d have no choice. And that’s what investment banks did. Their value add was to provide liquidity to the market in times of stress, they can’t do that anymore, since 2008. That ability of them to bring liquidity into a stressed market has been regulated away from them.

So you’re going to enter into a period of corporate bond downgrades at a time when the corporate bond market has never been bigger, with no liquidity provider anymore. And this is very specific to the U.S. because you haven’t had that growth of corporate debt elsewhere in the world. So I think the view that the U.S. is the cleanest dirty shirt is going to be severely, severely challenged in the coming year. Because look, you’ve had, again, a massive increase in corporate debt in the U.S. And that’s very specific, again, to the U.S. And a lot of that debt needs to get repriced at much higher rates.

Meb: Yeah. As we look at sort of U.S. economy, I mean, obviously, the interest rates ripping up and looking at you have some of my favorite charts, if we can talk you into sharing some of these, we’ll put them in the show notes. Because you do a great job on laying this out with charts. I’m a visual person, but looking at a lot of your topics. As we look out to 2023. It feels like everyone’s obsessed with the Fed. Does Powell pivot, is the bear market over it seems to be that you’re… and I’m putting words in your mouth. But you would say that there’s going to be more pain, as far as it comes to that view of the world. Is that accurate?

Louis-Vincent: It is. And perhaps one of the slides you can share, I can bring it up if you want. But I have this table where I look at the top 10 market caps at the end of every decade, in the late ’70s, six of the top 10 market caps in the world were energy stocks late ’80s, eight out of 10 with Japanese stocks, late ’90s eight out of 10 were telecom and Internet stocks 2000s It was all about how China was going to take over the world. And obviously the past decade, it’s all been about how software eats the world and you need to be in U.S. tech, etc. 10 out of the top 10 companies are tech stocks today. This has been the theme now the interesting thing when I show this table to clients they say oh yeah, the ’70s, ’80s, ’90s, 2000s Those were bubbles. But today, that’s not a bubble. These guys generate great cash flows. They have quasi-monopoly situations, which gives them the ability to bully governments. It’s very different this time. There’s this belief to your point, everybody’s talking about the Fed pivot. Everybody you talk to says oh, well, I need to wait for the Fed to cut interest rates again.

And then I can go back to buying Amazon and go back to buying Tesla and go back to buying Facebook. As soon as that happens. Forget it. Forget it. That bubble has now imploded. The markets already moving on to something else to me sitting around waiting all day for the Fed to cut interest rates so I can buy Facebook again, makes about as much sense as being in Tokyo in 1992. And thinking oh, when is the BOJ going to cut so I can buy bank of Tokyo Mitsubishi again? You had some great rallies in Japan through the ’90s. And you know, you could trade those rallies, but you want to play the fundamental trends and not a lot of people made money, and even though you had big rallies, not a lot of people made money in Japan in the ’90s because structurally, you were in a bear market. Again, bear markets are there for a reason. We’re in a bear market, bear markets are there to change the leadership, the bear markets 2011, it allowed to change leadership from everything’s about China to everything’s about U.S. tech. For me, the bear markets we’re in now is telling us time to change the leadership.

And by the way, when the Fed cuts sure you’ll get a rally in Facebook and in Google and everything else. But it will mark the starting gun for the massive outperformance of emerging markets. From the moment the Fed cuts, the U.S. dollar will really faceplant. This is when it’ll become obvious to people that actually most of the growth in the world over the next decade is going to occur in emerging markets. And this is where you need to be. So the Fed pivot does matter. And I think as you get financial accidents in the U.S. in 2023, you will see that Fed pivot, but to me, it won’t be a sign of oh, let’s go back to the previous winners.

Meb: I mean, the illustration of Japan alone, we talked a lot about it on the show, not just because I like to ski in Japan and hopefully get to revisit this year after many years of not going and we’re getting a nice discount on the yen.

Louis-Vincent: Very nice discount.

Meb: Right. The example you give is so true. I mean, look at the ’80s I mean, it was 30 years on a total return basis before that market got its head back above water. I’ve been trying to tell investors, as much as I love stocks for the long run, it’s going to be a lot longer than you think.

Louis-Vincent: Well, so interestingly, in Japan, in the ’80s, a lot of the bubble was around real estate and of course, banks. If you actually strip out the banks from the index, when you got to 1989 10 of the top 10 banks in the world were Japanese. The Japanese banks alone with 25% of the world MSCI just the Japanese banks, Japan was 45% of the world MSCI. I highlight this because yes, once the bubble imploded, everything collapsed, etc. But if you strip out the banks from the index, actually, the index didn’t take 30 years to make a new high, it came back pretty quickly. Because that was really the sort of central point of the bubble, right? So I highlight this because in the U.S., I think where the bubble was in tech funding any business model that was pretended to be tech, the WeWorks, the Beyond Meats, the Pelotons, all this stuff, you strip that part out. And I think the U.S. will come back very fast. It’s just that tech is 30% of the benchmark now, but you strip that part out the rest because the rest of the U.S. will do okay. The one hurdle for the industrials etc. Now is the strong dollar as the strong dollar rolls over, there’s no reason the John Deere’s and the Caterpillars of this world can’t go on going on.

Meb: Well, you’re speaking right to the heart of a value investor. But we talk a lot about this, we say look, a lot of the times value investing is fine. And everyone focuses on the value part you’re buying cheap stocks, or you’re buying an asset. But equally as important to that entire strategy is you’re avoiding the really crazy expensive stuff. And the problem with market cap weighting historically has been there’s no tether to value. So when you do have these giant booms, the really expensive stuff goes nuts. So Japan in the ’80s, my favorite bubble U.S. late ’90s. So just avoiding that sitting that out means you hopefully get to survive another day. And we talk a lot about how we think, even within the U.S. right now value or just anything other than the junk at the top can be probably a totally fine place to be. But that’s one of the big weaknesses of market cap weighting. And historically why we say it’s fine, but not optimal for us.

Louis-Vincent: And by the way on this, I think the equal cap weighted has been beating the crap out of the market cap weighted right. And that’s in spite of the Apples outperformance if you did it ex Apple, it would really beat the pants out of it.

Meb: Yeah, you had a great quote where you were talking basically the era coming up is going to be the return to the mean investor, where you’re starting to have this reversion. As we look out, you had a great slide where you’re talking about various rugby players and how they complement each other Americans we can talk about basketball team point guard, center, or whatever it may be. As we think about, you know, portfolio characteristics. We’re going to probably print one of the worst traditional portfolio years ever for most stock and bond investors in the U.S. We did a poll, we said are you down on the year? And it’s like 90% said, yeah, and it’s like 90% of ETFs are down. And we look out into the future. So we got the China part in emerging markets. Anything else that we didn’t talk about that you think are interesting areas to plug into the portfolio or to avoid as well?

Louis-Vincent: Yeah, absolutely. So to your point, I think there’s fundamentally three ways to make money in markets. You either run a return to the mean strategy, you run a momentum strategy, or you run a carry trade strategy. When you put on a trade, it’s very important that you know what that guy is doing for it. To your point. It’s like putting a team together, right? You mentioned basketball. You don’t expect your point guard to be the highest rebounder on your team. You don’t expect your center to shoot a bunch of threes. I mean, if they do, it’s great. But that’s not their job. That’s not why you put them on the court in the first place. And so as you build your portfolio, I think it’s very important to know, okay, if I buy this, what am I buying it for? Is this a return to the mean trade, momentum trade, carry trade, so that you can judge if he’s doing their job or not? Again, you’re not going to judge the point guard on his ability to rebound. I highlight this because for most people, you bought government bonds for their antifragile characteristics, you bought them thinking, well, if my equity is down 20%, then my bonds will be up 10. So that’s their job. And that job has failed massively this year.

The big failure in most people’s portfolio, whether you’re a pension fund, an endowment, a private investor, etc, isn’t as much as equities went down 20%, that’s part of the model, I would say, you buy equities, you accept that you might be down 20%, the part that has failed is that bonds haven’t done their job. Now, the fascinating thing to me is that we should acknowledge this, it’d be like a point guard who can’t shoot free throws, who went 0 for 10 at the free throw line. If you’re the coach you’d sub him out, it’s okay, you know what you’re out. You’ve lost it, you don’t have it. But if you show up today, to whatever wealth management firm you want to show up to, they’re going to give you a nice questionnaire, and they’re going to say, oh, you’re a conservative investor. So we’ll put 60% in bond 40% in equity, oh, you’re an aggressive investor, we’ll do 60% in equity, 40% in bonds, and then you tell them hold on. This hasn’t worked for two years now. But people still manage money the same way. Because it’s like, well, it worked for 25 years. So hopefully it goes back to working. What if it never works again? What if bonds and equities are now positively correlated, because we’re now in a structurally inflationary environment, then you need to completely reconsider your portfolio construction.

And I don’t think people are doing that yet. I mean, again, you still go to the wealth advisory firms, you still get the same questionnaire you were getting two years ago, and you still get broadly the same asset allocation. And they’re just sitting there crossing their fingers that the past two years were an anomaly. What if it is the new normal? What if this is now the world we live in, then you need to find different assets that are anti-fragile, different assets that protect your equity downside.

Now, in an inflationary environment, you need to basically get assets that benefit from inflation, not get assets that get hurt by inflation, assets that benefit from inflation are, of course, commodities, it’s energy, it’s emerging markets, it’s all the things that actually did diversify your portfolio a year ago, and my portfolio, I’m loaded up with energy, I have so much energy, and it’s not been doing well these past few weeks. But I almost don’t care because I’ve other stuff that’s doing well, right now, most notably, all my China stuff, it’s ripping higher. So my China stuff is ripping higher, my energy stuff is doing badly. It’s okay if tomorrow, energy prices go through the roof, my China stuff will sell off, but my energy stuff will do well, again, what would you own bonds for OECD government bonds for? Who’s going to buy these from you at a higher price? For what reason? And why should portfolios still have 40%, 50% built around those? To me, those are the questions investors should be asking themselves.

Meb: Yeah, I mean, always like thinking back investors to why you own an asset is such a basic, but also critical insight to work through and thinking about what role they play, and not just assuming that. I mean, bonds are such a great example, if you study history for past 100-plus years, you know, bonds don’t always hedge when stocks do poorly, sometimes they do. But sometimes they show up to the Christmas party, they drink too much. And that’s that, sorry. That’s who you get your crazy cousin showing up this year. As we start to wind down, what’s the view you hold that say 75% plus to the vast majority of the professional investing world does not hold could be right now or it could just be all the time, anything coming to mind?

Louis-Vincent: The view I would hold right now that most people don’t hold is how, excuse my French, but how screwed as an asset class the OECD government bonds are and how they’ve benefited from constant inflows from emerging markets. And how that is now structurally finished. A view I hold very dearly is we’ve completely undermined in the Western world, our single biggest comparative advantage, you know what we talked about, and that this is going to be reflected in lower and lower asset prices, especially for the asset prices that are perceived to be safe i.e. bonds in real estate. I think these two asset classes are almost condemned asset classes in the Western world. And we did this to ourselves like this is what’s so infuriating, is we did this to ourselves.

So my firm belief, I guess, to sum it up is the assets you think are safe, are far less safe than you think they are and the assets that you think are unsafe, are probably much safer than you think they are. People’s perception of safety is completely wrong. And partly because people equate safety with volatility, and if you look at periods that have countries that have gone through inflation, if you had your money in real estate or in bonds in Argentina, or in Brazil when they had big inflation, or in Zimbabwe or South Africa or wherever else, you got cleaned out, if you held equities, you actually did okay. It was volatile. But over the course of the cycle, you still did okay. So I think the view I hold dearly is actually equities. Today, given the macro environment, equities are much safer than bonds.

Meb: There’s a couple comments one was, I listened to a good podcast this week called Messi Economics, but it was talking about the perspective was an Argentine reporter, and I think it was on NPR was the show note links listeners, where an Argentine reporter talked about her childhood in Argentina, and then also kind of overlaid the experience of the soccer player Messi and kind of a lot of lessons about inflation and just moving out of Argentina and the flight from massive inflation. It’s a really eye-opening, I think, for a lot of investors, particularly in the U.S. who haven’t even thought about inflation, even at all in 30-plus years, and the vast majority of investing managers who are managing money today have never really experienced an inflationary environment. If you do, you’re probably 70. And no one’s listening to you anymore anyway. So you’re out playing golf, but we did a post during the pandemic called the Stay Rich Portfolio. And I love to do polls on Twitter to ask people questions, and just to kind of pro-sentiment. One of them is like, what do you do with your safe money? And everyone the assumption is T-bills or bonds, right? And we said, you hit on the examples, so accurate, which is people look at that on a nominal and volatility basis.

But after inflation, we say how much do you think T-bills or bonds have declined in the past on a real drawdown basis? Most people say like zero to 10%, few crazy, say 10 to 20, you know, and the answer is over 50, right? And so you can look at, you go through a thought experiment. And what we did is we looked at a global portfolio of global stocks, global real assets, and bonds, and then you mix that in with some cash. And you can’t say prove in our world, but you demonstrate, historically speaking, that’s actually a safer, safe money portfolio than just sitting in T-bills and bonds, which is what everyone does, and every corporation in the world does.

So anyway, that’s definitely in my non-consensus views as well. And I don’t know really many people that believe that besides me, but fun thought experiment to go through. Also why there’s so many yachts in Argentina, if you go down there, and various places in Latin America, if you look back on your career, what has been your most memorable investment, it could be good or bad. And you can also say, your most memorable call or position that you’ve had, over the years, there’s going to be thousands of them, I’m sure but anything come to mind?

Louis-Vincent: I don’t think thousands I think a career is made of three or four calls, to be honest. And if you get three or four right, you’ve had a pretty good career, for me, in terms of learning curve, both but also, frankly, money-making opportunity after the 2008 mortgage crisis. As a firm, we looked at the financial situation of most European countries, and we thought, the Euro is not going to be sustainable. All these European countries have had to issue massive amounts of debt to backstop their banks. And the market can’t carry that much debt. So they’re going to hit the wall. So I teamed up with a very good friend of mine called Mark Hart, and we set up a fund called the European Divergence Fund. And we did two things. We bought a bunch of CDS, credit default swaps on Greece, Portugal, etc, on the premise that credit spreads would widen.

And we bought a bunch of puts on the euro. And the premise said that the euro would tank. What was baffling was, we made a bunch of money on the credit default swaps, and we lost a bunch of money on the Euro puts because few people remember this, but basically between 2009 and 2011, the Euro went from 120 to 150. And it was very visible that Europe was hitting the wall, you know, Greece was going bankrupt, Italy was in dire straits. And as all this was happening, the Euro kept rising. I was like, What the hell is going on? Why am I getting my face ripped off over here being short, the euro, the fun in it, I’m making fine because we made lots of money on the credit default swaps. But we also lost a bunch on the euro. And I was talking about it with my dad who ran a macro firm in the ’80s and ’90s. And he told me, you should have tried being short Japan in the ’90s. Because by 1990, it was obvious that Japan had hit the wall. So he went short, the Nikkei, and he went short, the yen and the short Nikkei worked fine. And the yen went from 150 to 85 in 1994. So that means it’s going up. So the yen rose massively.

So in the end, you go through these episodes and you think okay, actually, when countries hit financial stress, you would think the currency would go down, but you can have a period where the currency actually shoots up as pension funds repatriate capital as banks repatriate capital as insurance companies repatriate capital, as everybody brings money back from abroad to plug the holes, and there’s nobody on the other side, then the currency can just go up in a vacuum. That’s what we saw in Europe in 2010, 2011. That’s what we saw in Japan in 91, 92, 93. I highlight this because everybody looks at the U.S. dollar as a sign of strength today. But could it be a consequence of the bear market? The U.S. has just had you lose 20% on equities us 20% on bonds. If you’re a U.S. pension fund if you’re a U.S. insurance company, are you bringing money back to sort of plug the domestic holes and as you do. You get these parabolic moves in the currency. I look at the U.S. dollar and I wonder is this a sign of strength or a sign of weakness with things on the other side.

So for me, that was one that European divergence trade was a big thing in my career. The second big thing in my career was China, decided to basically open a bond market in 2011. I saw this as a huge opportunity for our firm, I thought, how often am I going to be in the same starting blocks as Schroeder’s as PIMCO as Fidelity, they have as much of a track record on Chinese printing as I do, which is none because the market didn’t exist. So we built a pretty good Chinese fixed-income franchise. And we did so partly on the premise that if China was going to do this, they wanted to do it well. And our bet was that Chinese bonds would outperform most bond markets over any period. And if you look at the past 10 years, five years, three years, Chinese government bonds have outperformed U.S. Treasuries, JGBs. Because you had massive government support to that markets. And so one of the things I learned is, especially when it comes to bonds, especially when it comes to currencies, you don’t want to underestimate the strength of government. Through the past 10 years, everybody was telling you, the renminbi is going to collapse can’t invest in China can’t invest in Chinese bonds, and it was the best-performing market.

Meb: Well said, Louis, where do people find you? They want to read some of your work. Hear some more of your soothing voice, what’s the best place to go?

Louis-Vincent: Thank you very much. Well, the best place to go is our website. We have a website. It’s gavekal.com, gavekal.com. And from there, we do different things. We have a private wealth arm, we have an institutional money management arm, we have a research arm, so wherever people want to go, they can direct themselves from there, but that’s probably the best place. We do have a Gavekal Twitter feed, but you can sort of keep up to date with some stuff there. I don’t really post on Twitter or anything. I don’t have much of a social media presence. So the best thing is the website.

Meb: Or you can follow his Twitter account for some good charts and get your hands on because they’re great. Louis, thanks so much for joining us today.

Louis-Vincent: Absolutely. My pleasure. Thanks for having me.

Meb: Podcast listeners. We’ll post show notes to today’s conversation at mebfaber.com/podcast. If you love the show, if you hate it, shoot us feedback at [email protected]. We love to read the reviews please review us on iTunes and subscribe the show anywhere good podcasts are found. Thanks for listening friends and good investing.