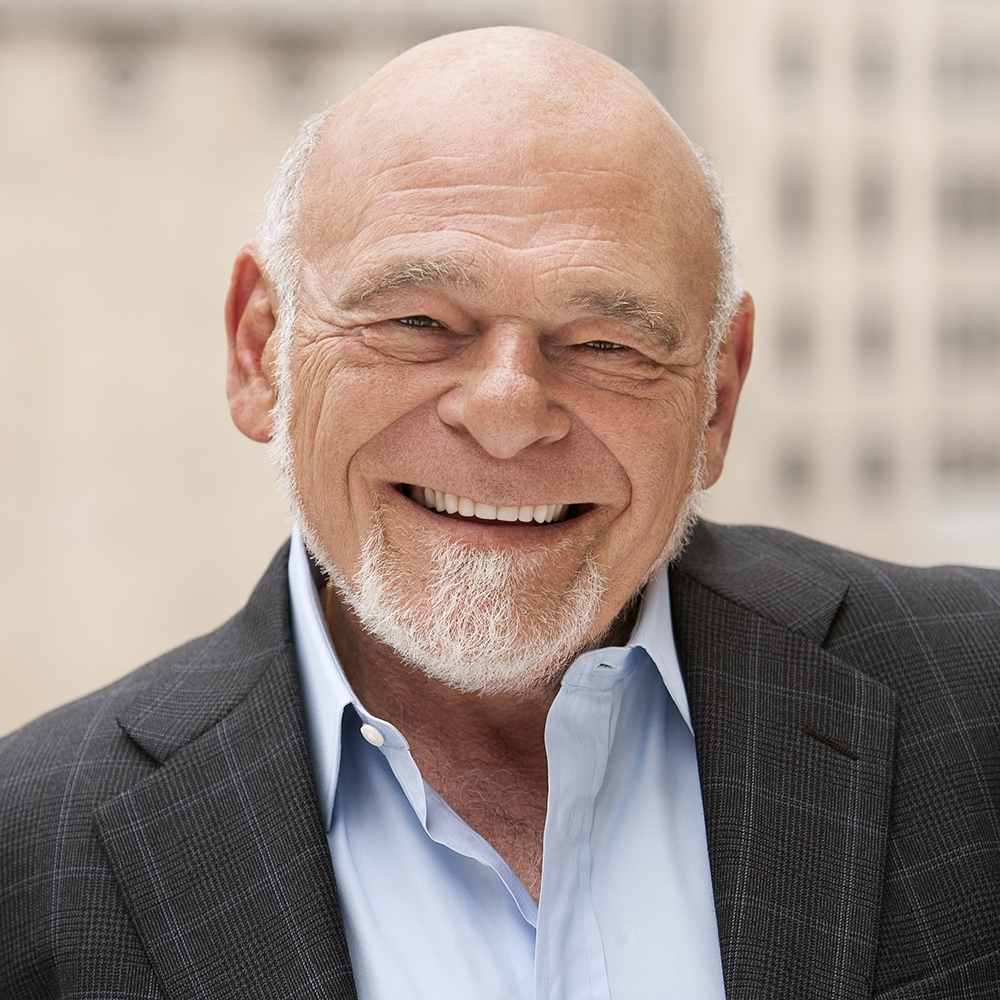

Episode #478: Sam Zell – The Grave Dancer on Private REITs, the Macro Landscape, & Timeless Investing Wisdom

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Guest: Sam Zell is the founder and chairman of Equity Group Investments, a private investment firm he founded more than 50 years ago. Sam’s thought to be the most successful real estate investor of all time and the man who known for his enormous success in real estate and “made REITs dance,” popularizing the REIT structure that’s commonplace today. He’s also been a successful investor in areas like energy, logistics, and health care.

Date Recorded: 4/3/2023 | Run-Time: 56:17

Summary: Today’s episode starts off with Sam’s take on the withdrawal limits for private REIT over the past few months from the lens of his quote, “liquidity equals value.” He shares his view on different areas of the real estate market, why he’s been a net seller for almost 7 to 8 years now, and some lessons from being a constant deal maker during his career.

As we wind down, Sam shares some advice for President Biden on how to help the economy and how to encourage more entrepreneurship in the US, and I promise you won’t want to miss his most memorable investment.

Sponsor: Farmland LP is one of the largest investment funds in the US focused on converting chemical-based conventional farmland to organic, sustainably-managed farmland using a value-add commercial real estate strategy in the agriculture sector. Since 2009, they have built a 15,000-acre portfolio representing over $200M in AUM.

Comments or suggestions? Interested in sponsoring an episode? Email us [email protected]

Links from the Episode:

- 0:39 – Sponsor: Farmland LP

- 1:42 – Intro

- 2:51 – Welcome to our guest, Sam Zell

- 2:51 – Sam’s take on Private REITs

- 9:51 – Reflecting on his experience in the 60’s and 70’s and contrasting it to today’s inflation

- 12:18 – Sam’s view on the current state of real estate

- 21:53 – Sam’s take on the macro environment

- 22:32 – Lessons from deals made in his career

- 23:54 – Sam’s take on risk management

- 25:14 – The Great Depression: A Diary

- 29:52 – Why Sam has been a net seller of real estate for almost a decade

- 40:22 – Sam’s most memorable investment

- 50:50 – Thoughts on how to incentivize and inspire the next generation of entrepreneurs

Transcript:

Welcome Message:

Welcome to the Meb Faber Show where the focus is on helping you grow and preserve your wealth. Join us as we discuss the craft of investing and uncover new and profitable ideas, all to help you grow wealthier and wiser. Better investing starts here.

Disclaimer:

Meb Faber is the co-founder and chief investment officer at Cambria Investment Management. Due to industry regulations he will not discuss any of Cambria’s funds on this podcast. All opinions expressed by podcast participants are solely their own opinions and do not reflect the opinion of Cambria Investment Management or its affiliates. For more information, visit cambriainvestments.com.

Sponsor Message:

Farmland LP is one of the largest investment funds in the US focused on converting conventional farmland to organic sustainably managed farmland and providing accredited investors access to the 3.7 trillion dollar farmland market in the United States. By combining decades of farming experience with modern technologies, Farmland LP seeks to generate competitive risk adjusted investing returns while supporting soil health, biodiversity, and water quality on every acre. And Farmland LP’s adherence to certified organic standards give investors’ confidence that its business practices align with their sustainable investing goals. In today’s world of high inflation, volatile markets and uncertainty, consider doing what other investors, including Bill Gates, pro athletes, and others, are doing and add farmland to your investment portfolio. To learn more about their latest offering, visit www.farmlandlp.com or email them at [email protected].

Meb:

Welcome, my friends. We have a true legend on the show today. Our guest is the grave dancer himself, Sam Zell, chairman of Equity Group Investments, a private firm he founded more than 50 years ago. Sam’s thought to be the most successful real estate investor of all time, the man known for his enormous success in popularizing the REIT structure that’s commonplace today. He’s also been a successful investor in areas like energy, logistics, and healthcare. We don’t get into Sam’s fascinating background, but I’ll point you to a wonderful interview with Tim Ferris. We’ll add a link in the show notes or check out Sam’s book as well.

Today’s episode though starts off with Sam’s take on the withdrawal limits and gating for private REITs over the past few months from the lens of his quote, “Liquidity equals value”. He shares his view on different areas of the real estate market, why he’s been a net seller for almost eight years now, and some of his lessons from him being a constant deal maker during his career. As we wind down, Sam shares some advice for President Biden on how to help the economy, how to encourage more entrepreneurship in the US, and I promise you don’t want to miss his most memorable investment. Please enjoy this episode with a legendary Sam Zell.

Meb:

Sam, welcome the show.

Sam:

Thank you.

Meb:

You talk a lot about a couple topics that really permeate, I feel like, a lot of themes, one of which is this concept of liquidity and value. And I got an email today, or a headline, that was talking about liquidity, particularly in your world with Blackstone, a company I know you’ve spent a lot of time dealing with, but thinking about liquidity with their real estate offering and getting gated, you’ve been around since the beginnings of kind of the development of the REIT industry. How do you think about REITs today, 2023, as an asset class?

Sam:

When Blackstone or Starwood or somebody else creates a quote “non-traded REIT,” as far as I’m concerned, the word non-traded means no price discovery. It’s evidenced by the fact that for a while there Blackstone couldn’t get out of their way with the amount of money that was pouring in. In the same manner, they couldn’t get out of their way with the amount of money started pouring out and they were forced to gate their fund. Real estate, by definition, unless it’s in a publicly traded vehicle with significant liquidity, is an illiquid instrument.

Now, there’s nothing wrong with investing in illiquid instruments as long as you understand that it’s illiquid. But I would suggest to you, and probably believe I’m right, that the majority of the people who invested in these non-traded REITs didn’t really understand what it meant and what they liked the most about it was that they got their monthly report from their broker and the number never changed, so therefore they didn’t lose money. But that’s not very realistic and not likely to perpetuate for very long. And so it wasn’t any big surprise that the non-traded REIT world became gated as the hedge fund world becomes gated when there’s a loss of liquidity.

Meb:

Yeah. Nothing triggered me over the years more than you see some of the marketing materials and people would talk about some of these interval funds that only mark maybe in their head once a year, once a quarter, and they say we have 4% volatility. And I say that’s funny because all of your assets, the public equivalents are 20% volatility so this magic transformation, creating something that’s extremely low ball out of something that probably isn’t. So as you’ve seen all this money flow in on the various offerings, REITs but also the public vehicles, interval funds, everything else in between, and you still have the same old story of liquidity mismatch. People get upside down, just saw it with Silicon Valley Bank, that it creates stressors. Is that creating any opportunities yet, do you think? Is it something that is just there’s always opportunities, but I’m just trying to think in my head, these giant passive vehicles that are just getting bigger and bigger.

Sam:

I think that so far in the real estate space, I don’t think there’s been much opportunity created, and frankly the opportunities won’t get created until the regulators force everybody to market. In ’73, ’74, in ’91, ’92, what created the opportunities was that the regulators came in and said, “You got to mark to market.” And once you mark to market, the values changed dramatically, and it created opportunities for people to participate in the downside of a particular scenario.

Meb:

Yeah. I like your quote where you say, “Liquidity equals value”. And so thinking about real estate in particular, but going through some of these cycles, early seventies is such a good example because I’m a quant, so I love looking at historical returns, and we’ve even tried to model quote “simulated REITs” back to 1900s and depending on where you start, if you start mid-seventies, it looks different than if you start in 1970. And same thing when people start something for the prior 10 years versus back to 2000. You pick up different downturns. But one of the things I wanted to ask you that I think is interesting to me, so I’m 45, the vast majority of my generation, even plus another 10, 20 years, has largely existed during one kind of macro regime. 1980s, 90s, 2000, 2010s, has been a world in the US of interest rates declining and really to a couple years ago and all of a sudden-

Sam:

And inflation declining.

Meb:

Right. And so you participated in a couple market cycles before that, the sixties and seventies, coming out of Michigan. How unprepared, or I like to think of everyone who’s managing money today in kind of the meat of their career, really never experienced that environment.

Sam:

That’s correct.

Meb:

What do you think, do you think that has implications? Do you see that as creating any sort of opportunities or structures because it seems to be like we are now in an environment that’s very unfamiliar for people who’ve been doing it for even 10, 20, 30 years.

Sam:

Yeah, I think that I have the benefit, or the burden, your choice of words, of having played in both scenarios. In the seventies, I remember closing alone in 1978 on the same day as the government produced an inflation rate of 13.3%. 13% inflation is a frightening idea and a frightening number, but that was [inaudible 00:09:22] in that period of time and consequently you had to operate and prepare and channel your capital to reflect the fact that 13% inflation rate was not out of hand and was certainly possible, and you had, as an investor, had to be prepared to pivot to reflect that.

Meb:

Yeah. At least it seems like it’s kind of coming down here in the US. Europe, who has a long history, painful history with inflation, is seeing some numbers that are getting perilously close to that double digit level you’re referencing. Now, doesn’t mean great businesses don’t get started and there’s plenty of good investing opportunities. It just means it’s different. And so how does that play into how you look? I know you do more than just real estate today, but you’ll be forever known as a real estate first guy. What does a real estate world look like to you today? We could start with commercial, but really anything in general. Is it the land of opportunity? Is this sort of inflation interest rates coming up really fast, is it creating problems that we just haven’t seen yet? What’s the world look like?

Sam:

Well, let’s see if I can break down your questions in some pieces. There’s very little doubt in my mind that the inflationary pressures in real estate are significant and have dramatically altered some prognostications. So the guy who four years ago took out a bullet loan, they came at 4% or 3%, and it comes due next February. He’s in a whole lot of trouble because he’s basically seen the value drop by 30 or 40% as the cost of capital has doubled. So I think that this unknown amount of unplanned refinancing that has to take place is going to potentially create some mark to market and some real challenges. As far as the overall real estate market is concerned, I’ve been a seller for probably seven or eight years except for a few examples in our public companies. Most everything we’ve done has been done with the objective of liquidating our positions because we couldn’t justify the prices that were being paid for existing real estate.

I mean, in some cases like office buildings and retail, a serious challenge as to what real value is. I mean, what’s the demand for office space going forward? I don’t know the answer to that, but I don’t want to be in front of the train that finds out. In the same manner, the online retail that was a non-existent 10 years ago now represents 13 or 14% of all retail sales. Well those retail sales are coming out of real estate. And what’s the impact of that, and how do you as an investor adjust for that kind of a thing? I mean, here in Chicago, 25% of Michigan Avenue, which was the number one retail space in the city, is vacant. Go to Madison Avenue, New York and take Madison from 52nd to 83rd and the amount of vacancy is alarming. I think they have the same situation in parts of LA.

So I think that we’re living through a pretty serious adjustment. At the same time, the demo space, the warehouse space, continues to be in very short supply. So what you’ve seen is like on a seesaw, you’ve seen retail and office go down and warehouse and demo go up. And of course the same thing is true in the residential space. Now the residential space is compounded by the fact that we’ve allowed not in my backyard to become a calling card for impairing development. As long as we continue to impair development, we’re going to have shortages. The number of people being added to the population is not being met by the housing creation, and that’s because we’ve made it so difficult and so expensive to add to the housing supply.

Meb:

As I hear you talk, I was thinking back, one of the challenges I have as being a quant, is looking back historically and understanding where there were very real meaningful sort of structural changes in markets. And so you mentioned too, certainly the post COVID work from home world, which feels very real, and in running my own company, but seeing other companies and friends too, something that just doesn’t flip a switch and go back, and then two, online for retail and other sort of trends. When you look back at your career in real estate, are there any others that really stand out as being like there was a moment that really flipped or before and after. It could be government induced legislation, it could be tax rates, it could be anything. What were some of the most impactful sort of before after macro?

Sam:

Start with the 1986 tax bill that all of a sudden changed real estate and took away the tax benefits. I mean, it used to be prior to the early eighties, tax benefits came with real estate as a way of compensating you for lack of liquidity. By the time we reached the mid-eighties, deals were being priced at x plus the value of the tax benefits. So in effect, the real value was being decreased for something that was maybe or maybe not relevant. In the same manner, you think about the changes that have occurred.

I tell people that when I got out of school, or when I was in college, if you went outside of the major cities, there were no apartments. There were primarily single family homes. And then all of a sudden we had a huge rush of apartments. Initially, very successful. Subsequently, as always is in the case, over supply. And today we’re probably closer to balance, although I’ll tell you from an affordability point of view, we definitely have a shortage of housing. But again, how do we create an affordability problem? By creating regulation, by creating that in my backyard, by creating an environment where land became an like accordion, and when demand was high, the accordion expanded, increasing the value of land and vice versa. Well that had a dramatic impact, the availability of multi-family housing.

Meb:

Listening to you talk about this is fun because thinking about the various changes, so I was an engineer, and I think the only econ class I took was econ 101, and I heard you talking about supply and demand and you mentioned a similar thing. It was like, I think the only thing I got out of this course, other than my professor always had the prettiest TAs in the world. That was what he was known for. If you went to Virginia, you know what I’m talking about. But this very concept of supply and demand, which seems to just permeate everything, right? It’s such a basic concept.

But thinking back to your time when you got started, one of the insights was, Hey, I’m looking into… It’s like the classic fishing, not on the main pond, but somewhere so not San Fran, New York, but maybe Ann Arbor or other places. How much do you think at this time, in this day and age, that’s become commoditized? Meaning if Sam’s coming out of Michigan today and he is thinking about real estate in particular, but applies to kind of everything, do you think that the similar takeaways from that concept is valid as far as opportunity? And where would you look? Where would Sam of today get started?

Sam:

I’m not sure I know where Sam would get started today, but what you’re talking about is what I referred to as the HP-12 factor. Somewhere around 1980, Hewlett Packard invented the HP-12. That meant that you could sit there in your office and you could do a 10-year analysis of a projection of a property and reach some conclusions. The result of which is that the commercial real estate market in the United States went from a very local market to a very national market. And so you could be sitting in Chicago and somebody could give you numbers on a real estate project in Reno, and you could use that as a base for deciding whether that was an attractive market or not. And once you’ve done that, if you felt it was attractive, you can go look at it. Prior to that, you just didn’t have the kind of information or the kind of putting together of information that allows you to reach conclusions.

Meb:

One more question on the macro, and then maybe we’ll hop over to the micro. I think one of the challenges as we wade through this period of one with higher inflation that may or may not be coming down, my guess is it’s going to be a little stickier, but who knows, and every once in a while you start to have the news cycle get dominated with things like the Fed, right? What are they doing? What’s going on? Because it does have a massive impact. And we’ve seen over the past few years, rightfully, wrongfully, people make decisions and then things change and they get into big trouble. So Silicon Valley Bank being the most obvious one recently, but maybe some more bodies floating to the surface we’ll see soon.

How do you think about the risks of the current environment when we talk about rates, we talk about inflation? Does this create a fair amount of… Let’s say Biden’s listens to you on the Meb Faber Show and says, “Sam, love listening to you on the podcast. Give me some advice. What should we be doing here in Washington to kind of smooth things out a bit? You got any good ideas for us?” What would you say?

Sam:

I’d say stop spending money you don’t have. There’s nothing more basic and nothing more deteriorating to value than inflation. Inflation is caused by too much money chasing too few opportunities.

Meb:

The Cambria Global Real Estate ETF, ticker BLDG, seeks income and capital appreciation by investing primarily in the securities of domestic and foreign companies principally engage in the real estate sector in real estate related industries that exhibit favorable multifactor metrics such as value, quality, and momentum. Learn how BLDG can help your portfolio.

Carefully consider the fund’s investment objectives, risk factors, charges, and expense before investing. This and other information can be found by visiting our website at cambrifunds.com. Read the perspective carefully before investing or sending money. Investing involves risks including potential loss of capital. Investing in foreign companies involves different risks than domestic based companies as operating environments vary from jurisdiction to jurisdiction. Investing in real estate poses different risks than investing in stocks and bonds. The Cambria ETFs are distributed by ALPS Distributors Inc, member [inaudible 00:21:47].

It’s particularly hard if you don’t put assets to work too, cash under the mattress. We did a poll just on our Twitter followers who most are professional investors, and I said, “Everyone spends all day thinking about investing. What’s the best investment? Is it time to buy gold? Is it time to sell stocks, whatever.” And then I said, “How much are you earning on your cash balance?” And the vast majority said either I don’t know or zero, right? And I said, “Well, we live in a world today where you can get four, and in a world of plus four inflation, if you’re at zero that that’s a pretty quick erosion.” Let’s kind of narrow it a little bit. You’ve done, man, I don’t know, hundreds, thousands of deals in your lifetime.

Sam:

A lot.

Meb:

A lot. I have a quote from you where you said… I was listening and you said, “Everything comes down to the deal.” So yes, we can talk about the macro and hey, real estate looks good, real estate looks bad, but really it comes down to the actual investment you’re making.

Sam:

People are constantly asking me the question, “What market do you want to invest in?” Or, “What trends are you following?” From my perspective, trends and markets and all of that stuff is very interesting, but you can have a bad deal in a hot market. You can have a good deal in a cold market. And it all comes down to what are the opportunities that that particular situation creates and what are the circumstances that you can bring to influence how you do?

Meb:

It’s so spot on. We talk like there’s a lot of startup investors and you talk about some of the down times, the big bear markets, and let’s say, some of the best companies were founded during… Uber, Google were founded during the downturns.

Sam:

Some of the best deals I ever made occurred during periods when there was stress.

Meb:

So speaking of stress, speaking of risk, which you talk about a lot, how do you think about it today? And this may have changed over the years and feel free to say if it has, but as you think about deals crossing your plate, you think about risk, evaluating it, what are the main things that come to mind today after a career at it, and what’s changed on your risk management scorecard when you look at deals today?

Sam:

I don’t really think a lot has changed on my risk scorecard. I love to quote Bernard Baruch, who as you know, survived the Depression by selling out before the market crashed. And his famous quote was, “Nobody ever went broke making a profit.” In the same manner, my focus has always been on the downside. My focus has always been how bad can it get, what are the variables that might change where I stand? So I focus on how bad it can get, what I can do to make it better, but always on the downside because if I’ve protected the downside, I can survive if the upside gets too good.

Meb:

Yeah, one of the benefits of looking back to history, you talk about the depression, listeners if you didn’t live through it, which is nearly all of us, there’s a great book called The Great Depression, A Diary by Benjamin Roth, but it’s a real time… It’s a lawyer, and he talks a lot about investing, and it’s a real time diary of his experience then. And it’s crazy to think about, and you think about stocks that declined 80% plus and everything else that happened, but the benefit to me of looking back through history is at least it gives you a anchor or framework to at least remember or understand what’s possible or what has at least happened in the past and realize it’s going to be even weirder in the future. But at least it’s crazy volatile enough in the past, which I think is way more than people think when they think about investments and the possibilities.

Sam:

Just think about how much the market went down in the great recession of ’07 and ’08 and ’09. I mean, we saw 70 and 80% reduction in valuations. Those are things that you tell your children about but you don’t live through. But we lived through it just like we lived through similar destructions of value in previous eras.

Meb:

One of the things about ’08, ’09, going back to the beginning of our conversation, is it was a market environment that the vast majority of people managing money going into ’08, ’09 had never been around. It’s very similar actually to the great depression. It was this very deflationary environment where kind of everything went down except for bonds, just about, but most everything went down. But we really hadn’t seen something, at least certainly to that magnitude too in a while, and I think it caught a lot of people off guard. But that’s the good times bring complacency, right? People get fat and happy. For someone who’s, you mentioned, has done a lot of deals, and the challenge the internet age too, of just limitless information, you could just spend infinite amount of time researching a company, how do you narrow it down to the key elements in deciding on what the key elements are for you? And I’m sure they’re different on each one, but what’s that process like? Do you have any suggestions on that for the listeners?

Sam:

Well, I guess that what I would say is that the single most underrated and misunderstood concept is competition. We all grow up and we take econ or we take economics in grade school, and the teacher tells us how terrific competition is and how terrific competition is for price discovery, et cetera, et cetera. But the reality is there’s nothing more frightening than competition. Given my choice, I would always have a monopoly rather than a competitive environment. And so when I look at potential investments, whether it be in real estate or in other things, first question I ask is what’s the competition? Who’s the competition? How is the competition financed? How does that finance compare to my financing? If things get tough, is the competition going to lower their prices to the point where they’re going to destroy my value? So I think more than anything else, I begin and end by looking for barriers to entry.

What is it that can protect me from uncontrolled competition, whether it be a patent, whether it be a unique location, whether it be a unique structure, whatever, I don’t know what it is, but when I look at businesses, whether it be real estate or otherwise, in terms of making investments, I’d start with and end with, what is the competition going to do to me and what could it do to me? And if I were outside of this little prism, how would I attack it or could I attack it and would it make sense to do so? But there’s nothing more deleterious than competition, and there’s nothing more you can misunderstand than how your competitor might respond to you.

Meb:

Particularly in our world, that was really well said, our world of asset management, it’s hard too, and you have to think about this ahead of time of, in a world of low interest rates and a lot of money sloshing around, competition also means these really giant, well-funded competitors. I joke about Vanguard a lot, who I love, but anytime you get a T after your name for [inaudible 00:30:10] for trillions, they have a lot more power to squeeze all the juice out of what they’re doing.

Sam:

We were just talking a few minutes ago about real estate and about the fact that I have not been a buyer for seven or eight years. It’s real simple. There’s been so much money, there’s been so much liquidity, that the value or pricing of assets in my judgment has gone beyond what makes sense for me. And so I’ve been a seller into that market. About six years ago we took over a public reach that had 12 billion dollars’ worth of assets called Commonwealth. It had 145 assets of which we’ve sold 141. I’ve sold 141 assets.

And I don’t have one regret. I don’t have one scenario where I said, “God, I wish I could get that back.” I don’t want any of it back because people paid me prices that I just couldn’t understand. And by the way, I think that’s another part of the whole equation. Everything you do should be understandable. When it isn’t understandable, when somebody is willing to make a long-term investment at 3% in an office building or an apartment project, I don’t understand. Maybe they’re right. So be it, but I don’t understand. And where I don’t understand, I don’t put my money.

Meb:

The funny thing about it, the older I get and the more we kind of watch what’s going on in markets and the world, a lot is driven by certainly career risks and incentives so there’s a lot of people out there that are just like their mandate is they have to put money to work and that’s it. Right?

Sam:

Other people’s money.

Meb:

Other people’s money. But the funny thing is you look around and each year it’s different, what sector, I mean we had one of the worst years ever for 60 40 last year, so one year it’s real estate, one year it’s commodities. I love the old chart of the tech sector versus energy over the past 40 years as a percentage of the S & P. And at one point energy used to be almost a third of the S & P. A couple years ago it got to two or three. It’s not going to zero. And now it’s up some, but if you just wait around long enough, it feels like Mr. Market eventually will deliver things around 50 or 70 or 90%. I mean there’s a lot of high flying investments from really the 2020, 2021, a lot of the SPACs market environment that are sitting down 80, 90%. So a lot of it just feels like people are having to do action for the sake of action.

Sam:

Well I’m not a quant, nor do I want to be a quant, but I’ve always avoided getting too statistically involved. I think that you can make the numbers say whatever you want them to say. I’m a basic person. I mean, if I buy a building, the first thing I ask is how much did it cost to build because if I pay too much, somebody else is going to be able to build across the street for less and compete with me. So I start with basic valuations and don’t allow myself to get caught up in the fury of the common man.

Meb:

Well the emotions, I mean there’s an old Buffett-Munger quote where they were talking to say… He’s talking about it’s not fear and greed that drives market, but envy, which seems to be a lot during the bull market part. The envy part sucks everyone in.

Sam:

You go to a cocktail party and the guy standing next to you just bought something or sold something or did something and you say, “Gee, I wish I had done that.” Well gee, I wish I had done that can be very influential but not necessarily productive.

Meb:

How many times when you’ve made an investment over the years, are you thinking of the exit or a potential exit when you enter in, so “Hey, I’m going to buy this investment. This is my margin of safety. Here’s wherever it can possibly go wrong.” But once you make the investment, are you thinking in your head, “I would like to sell this at X, whether it’s in three years, five years,” or is this something I just plan on holding for an indefinite… Are you planning the exit when you make the entry?

Sam:

I don’t think that I ever make an investment without looking at exit. I don’t think in terms of three to five years or 10 years or anything like that. I mean, a year ago or a little over a year ago, we sold the company that we owned for 37 years, and we probably wouldn’t have sold it if we didn’t think that circumstances were changing, and I didn’t like the risk of being there through such a change. So every single investment must have an exit. I don’t believe in calculating a pre-existing exit. And frankly, I think that we have a lot of institutional investors who view opportunities as six year plays or 10 year plays or five year plays. I’m not a good enough prognosticator to tell you what’s going to happen in five years, what’s going to happen in seven years. I do my evaluations every year, but I never ever forget that no investment is worthwhile unless you can exit.

Meb:

Yeah, I mean the reason we like to think through the construct on the entry… We asked people, we said, “When you buy something, do you at least think of sell criteria?” And I said, “It’s important not just for when things go south.” So you buy something, whether it’s a stock, whether it’s a building, shit happens, it goes down. That’s important to think through because you got to think of do you have liquidity? How are you going to get out? What’s the downside? But also on the upside, you make an investment and it’s going amazing. Also, it’s important because the people… You mentioned, you held something for 37 years, like the eventual five, 10 to a hundred bagger was once a two bagger. And it’s easy to try to take the gains too. So the emotions on both sides can be tough if you don’t think through it I think.

Sam:

What we haven’t discussed is staying power because staying power is critically important to that kind of an analysis. You may make an investment and it may not initially appear to work the way you would expect it. That’s acceptable if you have staying power and conviction. If you don’t have staying power and if you don’t have conviction, then the immediate response is sell. And I think a lot of mistakes have been made in the sales side as there had been on the buy side.

Meb:

Yeah, and like we tell people, everyone who has a garage, you go out your garage and look at all the stuff in your garage too. There becomes an emotional attachment to things you own, for better or for worse, than before you owned them. And so for a lot of people it can certainly disturb the logic of what they value something at and how they’ll get rid of it.

Sam:

Sure.

Meb:

Which reminds me, I got to clean out my garage because I got a bunch of junk in there.

Sam:

I don’t have a garage.

Meb:

Yeah, well I mean we renovated our house and I was like, we should have just cleaned house, started at zero with that thing and just gotten rid of everything, and it’s easier said than done.

Sam:

It’s hard. I mean, I have a list of investments that I should have gotten rid of years ago. You get attached to stuff.

Meb:

Yeah. Well, Sam, I come from a farming family, and there’s only a couple farmland REITs. I was always surprised that more farmland REITs didn’t get developed. As we look at the global market portfolio of assets, real estate, particularly single family housing, Ex US, and there’s more opportunities now, but farmland are two of the bigger areas that are hard to access from the little guy. But farmland for me has always been that asset that’s like pain in the butt and there hasn’t been a whole lot of return on the farmland side, but I keep it for different reasons, which are mostly emotional.

Sam:

But the answer is that REITs and various vehicles that create assemblages of real estate are all really predicated on income. And the farmland world has had a great shortage of income. So even today, I mean, you have a couple of farmland public companies out there that are earning one and a half, 2% on the thesis that, well, it’s food and it’s inflation, but all of that is irrelevant when at the end of the year you got one and half percent on your money and that doesn’t make a lot of sense.

Meb:

Let’s bounce around a couple more quick questions. You’ve been gracious sitting down with us this afternoon for a while. One of the questions we always ask the guests over the last couple years, and you got a lot to choose from, and I’m going to preface this by saying it doesn’t necessarily mean the best or the worst or whatnot. We say, “What has been your most memorable investment?” So it could be good, it could be bad, but when I say it, it’s just kind of seared in your brain of what is the most memorable, and you could say deal for you too, could be either, deal or investment you’ve been involved with.

Sam:

Well, somewhere in, I don’t know when it was, maybe it was 201 or 202, a guy came into my office and he explained that he was a pill manufacturer and that he manufactured pills pursuant to somebody else’s formula. And he was just a commodity player but that his specialty was a product called or a chemical called guaifenesin. Guaifenesin is an expectorant, and when you think about expectorant, Robitussin, stuff like that. And he explained to me that when the FDA was created in 1936, they had a problem and the problem was what do you do with grandfather drugs?

And so they put a provision in the bill that said that, in effect, grandfathered drugs did not have to be retested, but they were accepted just based on the fact they’d been around for a hundred years or whatever. But that if you took a grandfathered formula and proved new efficacy, then the government would give you a monopoly on effective use of that compound. And he explained to me that the number one grandfather drug was aspirin, which made sense, and guaifenesin was number two. And what he wanted to do was he wanted to basically come up with a long-lasting version of guaifenesin. And I thought about it, and I don’t obviously know nothing about drug compounds and I’m a real estate guy or I’m a hard asset guy and here’s some guy pitching me on drugs.

And so I thought about it and I decided to back it. And so I put up the money and we began the process of going through the FDA and doing drug trials and eventually we succeeded and we got the monopoly. We then named the product Mucinex, which as you know is an enormously successful expectorant that we were able to… I mean, I couldn’t believe how excited I was that we got approvals and we got a monopoly and eventually took the company public and then eventually sold the company. And it was, I don’t know, a 10 or 20 bagger, I don’t remember. But that was one of the most unique experiences I had as an investor. And when you ask the question, that’s kind of the first thought that came to my mind.

Meb:

I thought you were going to say they’d let you name it. You’re like, “Sam, what should we call this?” And you’re like, “Ah, I don’t know. Something about mucus… Mucinex. That’s it.”

Sam:

Yeah, I’ve always kept my ego out of everything I do.

Meb:

Easy to say, hard to do.

Sam:

Another example of what you’re asking was that in 1983, we were interested in purchasing a distributor of real estate products. At that time, there were a number of companies out there that syndicated real estate to the investors through the brokerage firms. And so we decided that we needed to be in that business because we were a big consumer of capital. And so we negotiated and finally found a company and agreed to buy it and agreed to the price and began the due diligence. And the guy in my shop that was responsible for doing the due diligence went to work. And I was sitting at my desk one day and the phone rang and it was Barry and I said, “Hi, how are you?” And he said, “Sam, I’ve discovered something that’s unbelievable.” And I said, “What’s that?” And he said, “I’m down here in Florida, I’m doing the due diligence on the deal, and I’ve discovered these mobile home parks.”

I said, “Mobile home parks?” He said, “Yeah.” I said, “That’s Marlon Brando and Stella and Rolling Cactus, and why would I want to touch something that was that far down the pike?” And he said, “Sam, you don’t understand that there is a mobile home park business that’s very different from what the street or what the world expects. These are age limited communities. They’re beautifully maintained. They’re the typical story of the guy who sells his house in Buffalo and buys a mobile home park in Sarasota. And it’s just a wonderful business.” And he proceeded to fill me in on the business. And I was stunned because I literally, here I am one of the biggest real estate players in the country and I never heard of it. And so we did our due diligence. We never bought the syndicator, but we bought the largest mobile home player in the country at a time when no one in the quote “commercial real estate business” owned mobile home parks to any extent.

And eventually we built the business up and took it public in 1993. And from 1993 to today, that mobile home park REIT has been the most successful REIT in existence during something like a 18% compounded rate of return. Interestingly enough, the real reason that it did so well is because of not in my backyard, going back to the very concept of competition because basically it was extraordinarily difficult to get zoning. So if you had mobile home parks and you had them and maintained them, not the dusty place on the edge town, but the crisp, clear, clean place that established its own situation, we made a fortune. So those are two examples of out of the park investments that certainly weren’t on my agenda.

Meb:

Yeah. Well, we should have started the conversation with these because I could listen to you tell stories about investments the whole time. I mean, think it’s so interesting because it informs… When Sam Zell name is in my head, I think just purely real estate, but you mentioned the story about Mucinex, and kind of applying the same risk methodology you just walked us through it. You’re like, well, here’s the steps. Here’s how I reduce the risk on thinking about it. I think that applies to really all of investing, all of life really. But you’ve now transitioned to being a majority non-real estate asset owner.

Sam:

Yeah, because back in 1980 we looked at the real commercial real estate world, and as I mentioned earlier, we saw taxes as becoming part of the quote unquote “value” not as compensation for loss of liquidity. And by recognizing that we shifted to non-real estate activities, and today 70% of our activities are non-real estate.

Meb:

Yeah. Let me squeeze in one more question before we let you end the evening. You’ve been involved in all sorts of deals, certainly investing over your career, but also in entrepreneurship and all the agony and ecstasy of being an entrepreneur. We don’t wish it upon anyone, but it’s one of the most American of all pursuits, but we got free markets and capitalism all over the world.

You have been involved in Michigan certainly with the education, and so let’s say you get another phone call, it’s Biden again, and he said, “Sam, I’m not going to listen to you about the spending because that’s crazy. I’m a politician. That’s what I do. However, I believe in the mission of trying to educate a, our youth on personal finance and investing, which we don’t teach in school, in high school.” There’s like 15% of high school… I think it’s actually up to 20 or 30% now. It used to be 15%. He goes, “Tell me some of the best learnings that you think, you know, a template on how we could really grow the teaching of this concept of both entrepreneurship and investing finance too, but really make it broadly applicable. You got any good ideas for us?

Sam:

Well, I’ve been very interested in entrepreneurship for a long time. I think I was interested in that area before it was called entrepreneurship. My favorite story is that in 1979, I was sitting with the dean of the University of Michigan Business School, and I had just read his curricula for the coming year. And I sat him down and I said, “I just read all the courses that you’re going to teach in the business school next year. And I never found the word entrepreneur.”

And I just couldn’t believe how could a business school exist and grow and educate without understanding the role of the entrepreneur, the role, the risk-taker, the role of a person who not only sees the problem but sees the solution and is willing to take the risk to achieve that solution and the rewards that come with it. Ours is a capitalistic society that has grown as a result of entrepreneurship, as a result of encouraging risk, as a result of encouraging people to follow their beliefs. Results have been, whether it be Steve Jobs or other entrepreneurial geniuses of our time, they’ve made a huge difference.

Meb:

Yeah, I’m hopeful though. The amount of startups we’ve seen with sort of, not only Y Combinator, but spreading across, it’s almost like a template, but even I think the QSBS rules that kind of were Obama era legislation, I think has done a lot to really get people interested in that world. And hopefully it’ll continue. So there’s no better education than actually trying to be an entrepreneur, whether you make it or not, but at least getting out there.

Sam:

Remember, for an entrepreneur, the word failure doesn’t exist. It just didn’t work out. And you get up off the floor and try again.

Meb:

My favorite example is we’ll talk to startup founders and they’ll say, “Look…” I was like, “You understand the math, right? That whatever, percent fail.” But they have the amazing naivete, “But that’s not going to be me.” Right? Every single one that’s starting a company, but not going to be me.

Sam:

That’s right. Not going to be me.

Meb:

Sam, it’s been a blessing. You have been a joy to listen to. I could do this all day. Thanks so much for joining us today.

Sam:

My pleasure. And I enjoyed it very much and it was really interesting. Thank you.

Meb:

If you ever make it out to Manhattan Beach, Sam, we’ll buy you lunch. I know you just spent a little time up Malibu. If you’re ever in the neighborhood, come say hi.

Sam:

You got a deal. Thank you.

Meb:

Podcast listeners, we’ll post show notes to today’s conversation at mebfaber.com/podcast. If you love the show, if you hate it, shoot us feedback at the Mebfabershow.com. We love to read the reviews. Please review us on iTunes and subscribe the show anywhere good podcasts are found. Thanks for listening, friends, and good investing.

Today’s podcast is sponsored by the Cambria Shareholder Yield ETF, ticker symbol SYLD. Looking for a different approach to income investing? SYLD has been engineered to help investors get exposure to quality value stocks that have returned the most cash to shareholders via dividends and net stock buybacks relative to the rest of the US stock universe. Visit www.cambriafunds.com/syld to learn more. To determine if this fund is an appropriate investment for you, carefully consider the fund’s investment objectives, risk factors, charges, and expense before investing. This and other information can be found in the fund’s full or summaries prospectus, which may be obtained by calling 855-383-4636, also ETF information, or visiting our website www.cambriafunds.com. Read the perspective carefully before investing or sending money. The Cambria ETFs are distributed by ALPS Distributors Inc, 1290 Broadway, Suite 1000, Denver, Colorado, 80203, which is not affiliated with Cambria Investment Management LP, the investment advisor for the fund.

There’s no guarantee the fund will achieve its investment goal. Investing involves risk, including the possible loss of principle. High yielding stocks are often speculative, high risk investments. The underlying holdings of the fund may be leveraged, which will expose the holdings to higher volatility and may accelerate the impact of any losses. These companies can be paying out more than they can support and may reduce their dividends or stop paying dividends at any time, which could have a material adverse effect on the stock price of these companies and the fund’s performance. Investments in smaller companies typically exhibit higher volatility. Narrowly focused funds typically exhibit higher volatility. The fund is managed using proprietary investment strategies and processes. There can be no guarantee these strategies and processes will produce the intended results and no guarantee that the fund will achieve its investment objective.

This could result in the fund’s under performance compared to other funds with similar investment objectives. There’s no guarantee dividends will be paid. Diversification may not protect against market loss. Shareholder yield refers to how much money shareholders receive from a company that is in the form of cash dividends, net stock repurchases, and debt reduction. Buybacks are also known as share repurchases, when a company buys its own outstanding shares to reduce the number of shares available on the open market, thus increasing the proportion of shares owned by investors. Companies buy back shares for a number of reasons, such as increase the value of remaining shares available by reducing the supply or to prevent other shareholders from taking a controlling stake.