Any ebook that intends to supply a whole account of a chapter protecting virtually 70 years within the historical past of concepts is an formidable achievement by itself, particularly when it’s centered round a fuzzy idea like neoliberalism. If such a ebook additionally makes an attempt to cowl a long time of financial historical past, discussing the evolution of policymaking and the mental and political debates that formed it, one would most likely fear that the writer is attempting to perform an excessive amount of. Now, add that the writer will attempt to take action whereas navigating murky waters, surrounded by the historical past of a violent dictatorship and the general context of Latin American politics of the Chilly Conflict period. It looks like a recipe for failure.

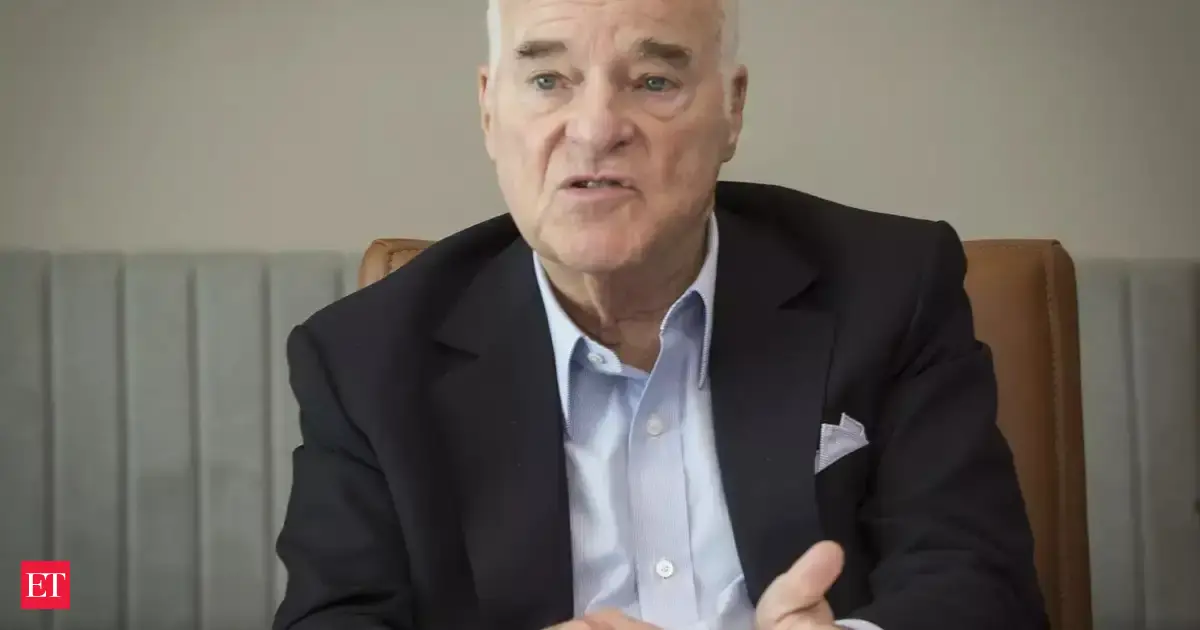

But, to the nice good thing about his readers, Sebástian Edwards accomplishes all this brilliantly. The Chile Undertaking: The Story of the Chicago Boys and the Downfall of Neoliberalism is nothing in need of a monumental achievement.

Undertaking overview

A local Chilean himself, Edwards acquired his bachelor from the Universidad Católica de Chile (Pontifical Catholic College of Chile, hereinafter PUC), labored as a younger economist in Allende’s authorities division of financial planning, and witnessed a well-known British scientist who was visiting Chile to name out the insanity of the duty: “my pal, you actually need to decide true, social, equilibrium costs for over three thousand items, with a fifteen-sector input-output matrix?” (p. 62). An opponent of Pinochet’s regime, he fled Chile in 1977, and acquired his graduate coaching in economics on the College of Chicago, the place he grew to become “colleague, coauthor, and shut pal of [Arnold] Al Harberger, who’s the mental father of the Chicago Boys.” (p. 23).

Whereas, because the subtitle suggests, The Chile Undertaking is especially a ebook concerning the story of the Chicago Boys and the rise and fall of neoliberalism in Chile, additionally it is a story of Chile’s fashionable financial historical past, advised in three elements.

The primary half (Chapters 1–3) units the stage for the rise of neoliberalism; from the deal between the College of Chicago and PUC, to Salvador Allende’s “one thousand days of socialism.” Edwards offers a cautious definition for neoliberalism:

- “I outline neoliberalism as a set of beliefs and coverage suggestions that emphasize the usage of market mechanisms to unravel most of society’s issues and wishes, together with the availability and allocation of social providers akin to training, old-age pensions, well being, assist for the humanities, and public transportation. […] neoliberalism is the marketization of virtually every thing” (p. 14, emphasis authentic).

Half two (Chapters 4–9) begins with Pinochet’s rise to energy and analyzes the financial insurance policies over the size of the dictatorship (1973–1990). This consists of debates over the preliminary shock remedy and Milton Friedman’s controversial visits to Chile (Ch. 4–5), the struggles for command over coverage throughout the regime (Ch. 6), and the small print about their eventual implementation (Ch. 7). Chapter 8 offers with the deep foreign money disaster of 1982, and the second half ends with an evaluation of the second spherical of “pragmatic” reforms that comply with the disaster in Chapter 9. The latter additionally explores the rising affect of Arnold Harberger, who was probably the person influencing the “pragmatic” half. Half two shines as a result of concept and historical past come collectively to ship a captivating story that reads virtually like a novel.

The ultimate a part of the ebook (Chapters 10–16) covers the autumn of Pinochet’s regime and the collection of financial reforms that continued beneath democracy. This half tells a narrative of the mannequin that led to Chile’s financial miracle, but in addition of its downfall. It began with a collection of protests and riots in 2019 that finally led to an formidable try to draft a wholly new structure that finally failed. Whereas the tip appears sure, Edwards additionally delves into its potential causes, drawing from a perceived widespread sentiment of unhappiness: “massive numbers of Chileans lived in worry of retrogressing each socially and economically and rejoining the ranks of the poor,” (p. 209) which grew to become often called the malestar (“malaise”) speculation.

“Edwards’ first-hand testimony, mixed together with his use of archival materials, offers a wealthy historic account.”

Edwards’ first-hand testimony, mixed together with his use of archival materials, offers a wealthy historic account. Many of those occasions are surrounded by controversy, and a few have been elevated to the standing of outright myths. Edwards acknowledges upfront the constraints of what the archive tells us and is evident when he’s filling the gaps together with his conjectures. The result’s an especially well-balanced narrative that – maybe aside from a extra technical chapter coping with the foreign money disaster – is accessible for a extra normal viewers. Thus, the primary contribution of the ebook is to supply new (and, in some instances, arguably definitive) historic accounts of key occasions of Chile’s latest financial historical past.

Clarifying misconceptions

The settlement between the College of Chicago and the Universidad Católica de Chile (PUC) is the topic of an necessary false impression. It’s typically portrayed as a nebulous U.S. plan to coach economists particularly to run Pinochet’s financial coverage. But the plan was drafted in 1954–55, a decade and a half earlier than even Allende rose to energy, to not point out Pinochet.

Edwards attracts from archival data and divulges that the U. Chicago-PUC deal was, in some ways, unintended. The deal was intermediated by the Worldwide Cooperation Administration (ICA), and it first aimed on the Universidad de Chile, the nation’s major public college, not PUC. Nevertheless, “the [U. de Chile] college was reluctant to enter right into a partnership with an American faculty, and significantly with the College of Chicago, with its popularity of being a white knight for monetarism, free commerce, deregulation, and free markets” (p. 29). When the ICA reached out to PUC for the same deal, each U. Chicago and PUC had issues concerning the compatibility of the college’s spiritual affiliation. Finally, PUC’s dean manifested their “need is to signal an settlement between our college and an establishment in america, such because the College of Chicago, or the Massachusetts Institute of Know-how.” (quoted in pp. 30–31). Thus, it was not clear from both the U.S. or Chilean facet that the College of Chicago can be finally paired with PUC.

The federal government of Salvador Allende can be the topic of many misconceptions. Edwards acknowledges that a part of the confusion stems from the truth that Allende was from the Socialist (and never from the Communist) Get together, which led authors to mistakenly painting him as a comparatively reasonable candidate regardless that, in Chile, the Socialists had been way more to the left and had shut ties with Cuba and North Korea.

The ebook provides an in depth overview of Allende’s financial insurance policies. As an illustration, Edwards reveals that the federal government’s grasp over the economic system went considerably past the well-known nationalization of U.S.-owned copper mines. It additionally nationalized the banking sector and enforced its proper to take management, for an undetermined interval, of a whole lot of factories producing items “in brief provide.” This quick provide was typically staged by unions stopping the manufacturing unit ground and creating synthetic shortages. He notes that each import required a license, with some tariffs reaching 250 %. He additionally describes how perverse and arbitrary mechanisms had been used to set worth controls, which led to confiscation of products, typically imposed big fines, and, typically, despatched “speculators” to jail.

Turning to controversy

Half II of the ebook sheds mild on extra controversial subjects: the Chicago Boys’ involvement within the Pinochet regime. Some early accounts attributed the financial plan to the CIA and positioned Arnold Harberger and Milton Friedman as maybe main contributors. Edwards once more relied on archival supplies and interviewed a number of of the Chicago Boys themselves to supply, it appears, a balanced account.

The plan was often called El Ladrillo (The Brick), as a result of its sheer dimension. The controversy is whether or not the plan was knowingly drafted by the economists for Pinochet. What is understood is that the plan was written earlier than the coup, in 1972, as a blueprint for Chile’s improvement within the subsequent presidential elections; eleven of the Chicago Boys contributed particular person chapters.

On the one hand, it seems that solely one in all them, Emilio Sanfuentes, then related to the Chilean assume tank Centro de Estudios Sociales y Económicos, had contact with a retired high-ranking navy official who labored for a personal conglomerate and was enthusiastic about such a plan. Edwards additionally recollects that a lot of the content material of the plan had been fairly much like an earlier financial plan written by a number of the similar Chicago Boys for presidential Jorge Alessandri, a center-right candidate who confronted Salvador Allende in 1970, and had been additionally seen as extension to stories that two of the economists (Alvaro Bardón and Sergio Undurraga) had been writing for the opposition, together with the reasonable Christian Democrats and former president Eduardo Frei Montalva.

Edwards highlights that the latter plan, El Ladrillo, included extra economists, a few of them centrists. The principle editor of the plan, Sergio de Castro, argued that to achieve the assist of Christian Democrats, it even included recommendations of “Yugoslavia-style corporations, the place employees owned the businesses and took part actively of their administration” (Arancibia Clavel and Balart Páez 2007, p. 144). He additionally emphasizes the concept solely Emilio Sanfuentes had connections with navy officers.

However, there may be proof that each one authors met in a lodge to debate it with the retired naval officer liaison. Edwards acknowledges that it’s finally a “thriller that can by no means be totally resolved” (p. 80), however doesn’t draw back from conjecturing that it’s probably that the remainder of the economists knew, at the very least to some extent, that the plan was supposed for the navy.

In what follows, Edwards offers a complete evaluation of the insurance policies contained within the plan. For each coverage space (e.g., healthcare), he compares what the plan proposed and what was finally applied by the navy, creating an especially helpful information to researchers. One other assertion to Edwards’s thoroughness is that he connects some coverage selections to theoretical debates that had been going down on the time, each in Chile and elsewhere.

Friedman’s position

Chapter 5 provides a fastidiously researched examination of Milton Friedman’s involvement with the Chicago Boys and his two visits to Chile in the course of the navy regime. Friedman first visited Chile between March 20 and 27, 1975, and met with Pinochet on the 21st. Of their one-hour assembly, Friedman argued—in seemingly broad strokes—that the nation wanted a “shock remedy” to battle rampant inflation that had reached 350% a 12 months.

“Certainly, the director of intelligence was spying on the Chicago Boys to persuade Pinochet that ‘the Chicago Boys weren’t true patriots and that their solely curiosity was to denationalise state-owned enterprises at low costs so as to have non-public traders (together with their mates and associates) personal and run key strategic industries.’”

Within the following days, Friedman met with Chile’s enterprise elite, gave a lecture to a gaggle of navy officers, and gave a number of interviews to newspapers. Friedman once more argued for shock remedy. Edwards collects a number of the questions requested by the enterprise viewers and Friedman’s reply to them, concluding that businessmen wished the identical gradualism they had been used to.

The navy was largely towards privatizations and reducing pointless personnel wanted for the fiscal adjustment. Certainly, the director of intelligence was spying on the Chicago Boys to persuade Pinochet that “the Chicago Boys weren’t true patriots and that their solely curiosity was to denationalise state-owned enterprises at low costs so as to have non-public traders (together with their mates and associates) personal and run key strategic industries.” (p. 100).

Whereas critics deal with Friedman because the mastermind behind Chile’s 1975 Restoration Plan, the Chicago Boys themselves downplayed Friedman’s affect. A number of biographies don’t point out Friedman’s go to to Chile in any respect. Earlier analysis additionally urged that he didn’t affect the plan (see Caldwell and Montes, 2015, p. 271). Extra broadly, Friedman defended himself by arguing that assembly a politician just isn’t the identical as advising him, and by noting that he additionally met with Chinese language chief Zhao Ziyang in 1988. Furthermore, what he mentioned about Chile was a mere reflection of broad classes from his tutorial analysis, not particular recommendation.

Nevertheless, Edwards makes a convincing case that Friedman is chargeable for the restoration plan, referring to the significance of a “earlier than Friedman and an after Friedman.” (p. 97, emphasis authentic). The Chicago Boys would probably have proposed the identical plan regardless, however Friedman’s go to weighed the scales in favor of their plan over the extra gradualist strategy that was being put forth by businessmen and navy officers.

What to make of the Chicago Boys?

Recurring in Edwards’ narrative within the third and closing a part of the ebook is that, regardless of the breadth of the reforms applied throughout the regime, a lot else was additionally performed after the return to democracy to deepen and lengthen the reforms. This continuation was typically undertaken by center-left politicians. This perception invitations reflection on the position Chicago Boys. On the one hand, their concepts undoubtedly charted the trail to larger financial freedom, a lot wanted in Chile after Allende’s populist insurance policies.

However, Chile’s expertise highlights the constraints to financial progress and prosperity beneath a dictatorship. Latest empirical analysis has analyzed this concern in Pinochet’s Chile from two totally different sides. Escalante (2022) reveals that the Chilean GDP per capita underperformed for at the very least the primary 15 years following the coup. Arenas, Toni, and Paniagua (2024) additionally query the timing of the “Chilean miracle”, arguing that it solely actually developed following the return to democracy. Certainly, different Latin American improvement “miracles” (in Uruguay and Costa Rica) occurred with out a comparable story of a liberalizing autocrat.

For extra on these subjects, see

Nonetheless, it’s simple that the Chicago Boys utterly shifted the Overton window in Chile. Even when by historic accident, they remodeled perceptions of insurance policies that had been unimaginable in Latin America right into a established order that endured because the nation returned to democracy. Hopefully, Chile can even endure its new challenges.

Word:

I refer the readers to a different overview of the ebook by Pablo Paniagua, which offers extra extensively with Edwards’ speculation concerning the downfall of liberalism in Chile: the “malaise” speculation.

Footnotes

[1] Sebastian Edwards (2023) The Chile Undertaking: The Story of the Chicago Boys and the Downfall of Neoliberalism. Princeton College Press.

[2] To readers conversant in Edwards’s work on populism (see esp. Dornbusch and Edwards, 1990), it’s no secret that Allende’s macroeconomic insurance policies had been disastrous, resulting in hyperinflation in 1973.

[3] “You will need to level out that solely one of many members of the educational group [Emilio Sanfuentes] had contact with the excessive command of the nationwide Navy, one thing the remainder of us didn’t learn about. Thus, [in September 1973,] our shock was immense after we realized that the Junta had our doc and was considering the doable implementation [of our suggested policies].” (De Castro, 1992, p. 11, as quoted in Edwards, p. 78)

[4] As an illustration, Edwards connects the macroeconomic insurance policies put ahead in The Brick to Albert Hirschman’s “The Dynamics of Inflation in Chile,” revealed in 1963.

[5] Edwards goes deep into the archives to light up the context of Friedman’s go to to Chile, additionally counting on Friedman’s personal recollections.

[6] In the course of the awarding of the 1976 Nobel Prize in Economics to Friedman, as he was about to be launched to King Carl XVI Gustaf of Sweden, a demonstrator screamed from the balcony: “Freedom for Chile! Friedman go residence! Lengthy stay the individuals of Chile! Crush capitalism!”

[7] Friedman additionally visited Chile a second time, in November 1981, to attend a gathering of the Mont Pèlerin Society.

References

Arancibia Clavel, P., and Balart Páez, F. (2007). Sergio de Castro: El arquitecto del modelo económico chileno. Santiago, Chile: Editorial Biblioteca Americana.

Arenas, J., Toni, E., & Paniagua, P. (2024). Growth on the Level of a Bayonet? Difficult Authoritarian Narratives in Latin-American Development. https://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.5026133

Caldwell, B., and Montes, L. (2015). “Friedrich Hayek and His Visits to Chile.” Assessment of Austrian Economics 28(3): 261–309.

De Castro, S. (1992). El ladrillo: Bases de la política económica del gobierno militar chileno. Santiago, Chile: Centro de Estudios Públicos.

Escalante, E. E. (2022). The affect of Pinochet on the Chilean miracle. Latin American Analysis Assessment, 57(4), 831–847.