Inflation is among the many most essential financial dangers confronted by particular person traders. Following the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic and the struggle in Ukraine, inflation resurfaced in lots of nations. Due to this rising inflation and the more and more essential position particular person traders play in capital markets, a rising variety of articles within the monetary press focus on how particular person traders might protect the true worth of their monetary wealth in opposition to rising costs, with a lot of them pointing towards investments in shares.1 Nevertheless, little is understood about how particular person traders truly reply to the prospect of upper inflation, and principle offers conflicting hypotheses on this difficulty. On the one hand, the hedging speculation predicts that traders are extra doubtless to purchase and fewer more likely to promote shares when anticipated inflation will increase. It is because traders perceive that shares entitle them to a fraction of the earnings generated by the underlying actual property, permitting them to protect the true worth of their investments (e.g. Fama and Schwert 1977, Fama 1981, Boudoukh and Richardson 1993, Bekaert and Wang 2010). Alternatively, the cash phantasm speculation means that traders are much less doubtless to purchase and extra more likely to promote shares in durations of upper anticipated inflation. It is because they modify nominal rates of interest however ignore that companies’ money flows additionally develop with inflation, main them to require increased dividend yields to carry shares (e.g. Modigliani and Cohn 1979, Ritter and Warr 2002, Cohen et al. 2005). Given these two competing hypotheses, understanding how particular person traders react to anticipated inflation is an empirical query.

Germany within the Nineteen Twenties as a laboratory

A check of particular person traders’ response to inflation is topic to 3 most important empirical challenges. First, one wants granular information on traders’ safety transactions. This permits for direct evaluation of funding decision-making in inflationary durations. Second, one wants a interval by which inflation, if neglected, produces sizable monetary losses and thus attracts the eye of traders.2 Third, one wants a dependable measure of anticipated inflation that varies each over time and throughout traders. It is a crucial situation for a within-person evaluation and permits one to manage for the general time development.

This setup will not be accessible in the commonest investor-level datasets. In a brand new examine (Braggion et al. 2022), we introduce a singular dataset containing safety portfolios of over 2,000 personal purchasers of a German financial institution between 1920 and 1924, the interval of the German hyperinflation. The info and the time are ideally suited to handle every of the empirical challenges outlined above. First, we now have detailed data on each commerce executed by the financial institution’s purchasers, permitting for direct evaluation of people’ funding behaviour. Second, inflation was excessive between January 1920 and September 1923, doubtlessly yielding giant monetary losses if neglected and arguably grabbing traders’ consideration. Third, we now have inflation information at a month-to-month frequency for tons of of cities in Germany, leading to an inflation measure that captures inflation skilled regionally over time, which ought to be a dependable proxy for anticipated inflation.3

Particular person traders purchase much less (promote extra) shares when dealing with increased inflation

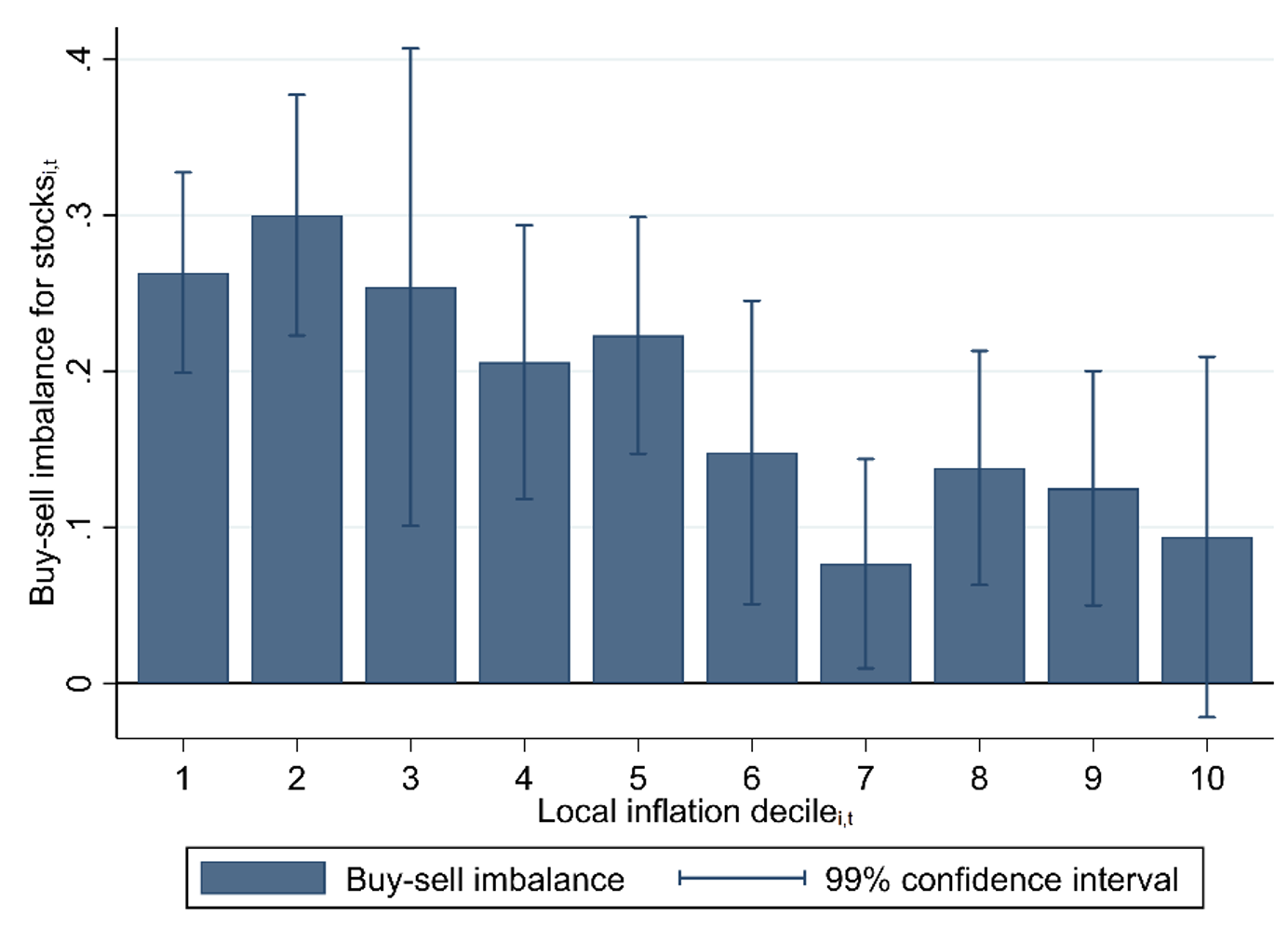

Determine 1 visualises our most important discovering. Every month, we kind cities in Germany into deciles based mostly on their native inflation and compute, for every inflation decile, the common buy-sell imbalance for inventory trades of purchasers dwelling in these cities. The buy-sell imbalance captures particular person traders’ internet demand for shares. We then plot common buy-sell imbalances in opposition to inflation deciles. The determine reveals a powerful detrimental relationship between the 2. This means that traders purchase much less (promote extra) shares when dealing with increased native inflation. Transferring from the decile with the bottom inflation to the decile with the best inflation reduces buy-sell imbalances by 17 share factors. Extra formal regression-based analyses verify this consequence. Therefore, we discover investor behaviour per the cash phantasm speculation however inconsistent with the hedging speculation.

Determine 1 Native inflation and inventory trades

In extra assessments, we discover the detrimental relationship between native inflation and buy-sell imbalances for shares to be attenuated for extra subtle purchasers. For institutional purchasers of our financial institution, we even doc a constructive affiliation between native inflation and buy-sell imbalances. These findings help the notion that sophistication reduces cash phantasm.

We additionally discover a constructive relationship between native inflation and foregone actual returns following inventory gross sales, suggesting that traders dealing with increased native inflation mistime their gross sales and incur further losses. This proof is once more per traders committing an inflation-induced funding mistake.

A lot of robustness assessments point out that our findings are unlikely to be pushed by traders utilizing native inflation as a proxy for future financial outcomes, by traders’ danger aversion growing with native inflation, by traders liquidating shares to fulfill consumption wants, and by traders shifting to different asset lessons additionally providing a hedge in opposition to inflation.

Conclusion

Our evaluation offers proof that particular person traders, specifically unsophisticated ones, make inflation-induced buying and selling errors. This stresses the significance of the continued debate on the monetary literacy of people. Not too long ago, the European Fee pointed towards the restricted monetary literacy of households and advocated for making monetary training a precedence for Europe. Comparable calls had been made within the US.4 Our findings underscore issues that the monetary literacy of people might not be adequate to reply appropriately to the presently resurfacing inflation.

References

Bekaert, G and X Wang (2010), “Inflation danger and the inflation danger premium”, Financial Coverage 25(64) 755–806.

Boudoukh, J and M Richardson (1993), “Inventory returns and inflation: An extended-horizon perspective”, American Financial Evaluate 83(5) 1346–1355.

Braggion, F, F von Meyerinck, and N Schaub (2022), “Inflation and particular person traders’ habits: Proof from the German hyperinflation”, CEPR Dialogue Paper No. DP15947.

Cohen, R B, C Polk, and T Vuolteenaho (2005), “Cash phantasm within the inventory market: The Modigliani-Cohn speculation”, Quarterly Journal of Economics 120(2) 639–668.

D’Acunto, F, U Malmendier, J Ospina, and M Weber (2021), “Publicity to grocery costs and inflation expectations”, Journal of Political Financial system 129(5) 1615–1639.

Fama, E F (1981), “Inventory returns, actual exercise, inflation, and cash”, American Financial Evaluate 71(4) 545–565.

Fama, E F and G W Schwert (1977), “Asset returns and inflation”, Journal of Monetary Economics 5(2) 115–146.

Katz, M, H Lustig, and L Larsen (2017), “Are shares actual property? Sticky low cost charges in inventory markets”, Evaluate of Monetary Research 30(2) 539–587.

Malmendier, U and S Nagel (2016), “Studying from inflation experiences”, Quarterly Journal of Economics 131(1) 53–87.

Mankiw, N G and R Reis (2002), “Sticky data versus sticky costs: A proposal to switch the brand new Keynesian Phillips curve”, Quarterly Journal of Economics 117(4) 1295–1328.

Modigliani, F and R A Cohn (1979), “Inflation, rational valuation and the market”, Monetary Analyst Journal 35(2) 24–44.

Ritter, J R and R S Warr (2002), “The decline of inflation and the Bull Market of 1982-1999”, Journal of Monetary and Quantitative Evaluation 37(1) 29–61.

Sims, C A (2003), “Implications of rational inattention”, Journal of Financial Economics 50(3) 665–690.

Endnotes

1 See, for instance, “Inflation is coming. How a lot, for a way lengthy?”, New York Occasions, 6 June 2021; “Inflation poses a length downside for traders”, Monetary Occasions, 16 June 2021; “Inflation might imply worth shares’ time to shine”, Wall Avenue Journal, 26 October 2021; “Greatest investments to beat inflation”, Forbes, 28 December 2021; “Flight to ‘secure haven’ funds runs its personal danger”, Monetary Occasions, 7 March 2022; “Shares as inflation hedge is new catch-all narrative for market rally”, Bloomberg, 22 March 2022.

2 In durations of low inflation, traders could not react to inflation due to rational inattention (e.g. Mankiw and Reis 2002, Sims 2003, Katz et al. 2017).

3 Current empirical work reveals that the inflation skilled personally is a vital determinant of people’ inflation expectations (e.g. Malmendier and Nagel 2016, D’Acunto et al. 2021).

4 See, for instance, “‘We want folks to know the ABC of finance’: dealing with as much as the monetary literacy disaster”; Monetary Occasions, 4 October 2021; “Training Secretary Miguel Cardona says private finance classes ought to begin as early as attainable”, CNBC, 13 October 2021; “Enhancing monetary literacy have to be a precedence for Europe”, Monetary Occasions, 17 January 2022.