Executives across the Fortune 500 landscape face a question they can’t afford to misunderstand: How do we govern systems we don’t fully understand?

For systems focused on or built around technology, the standard playbook for managing risk and getting things under control assumes some level of predictability. In such a world, you audit code, test edge cases, and certify compliance accordingly.

But when AI systems make decisions through mechanisms that even their creators struggle to explain, the standard playbook quickly becomes dangerously inadequate.

That said, the really critical questions leaders must ask, particularly when it comes to “governing the ungovernable,” are now:

1) Can we identify why an AI system failed?

2) Can we fix it without creating new problems? And,

3) Can we confirm the fix actually worked?

For CEOs navigating this landscape, the stakes extend beyond just reputation or regulatory fines. They touch on the fundamental question of organizational control.

The Illusion of Explanation

These days, most AI systems operate as black boxes with “post hoc” explanations attached. In such cases, an AI model will often flag a transaction as fraudulent, recommend a hiring decision, or dynamically adjust pricing, providing an explanation only after the fact, reverse-engineered to sound realistic and justifiable.

The problem is that plausibility and causality are not the same thing. Such explanations can sound coherent while falling apart under even the slightest intervention. By changing just one input variable, the entire rationale collapses, revealing that the system was never operating according to the logic it claimed in the first place.

The gap between narrative and mechanism here creates two categories of risk that traditional governance frameworks are simply not designed to handle.

1) Hidden Failure

First comes the hidden failure mode. When a system’s internal logic is unclear, failures can spread in ways no amount of testing will catch in advance. A change intended to improve one outcome can hurt performance elsewhere, usually in ways that only emerge under specific and rare conditions.

2) Intervention Fragility

Second is the issue of intervention fragility. In such cases, even when a problem is identified, fixing it becomes a high-stakes gamble. Adjusting one component may trigger compensatory behaviors in other parts of the AI system, creating new failure modes that are harder to detect than the original problem.

For organizations that rely on AI to make consequential decisions at scale, this is not a hypothetical concern. It’s an operational liability.

What Debuggability Actually Means

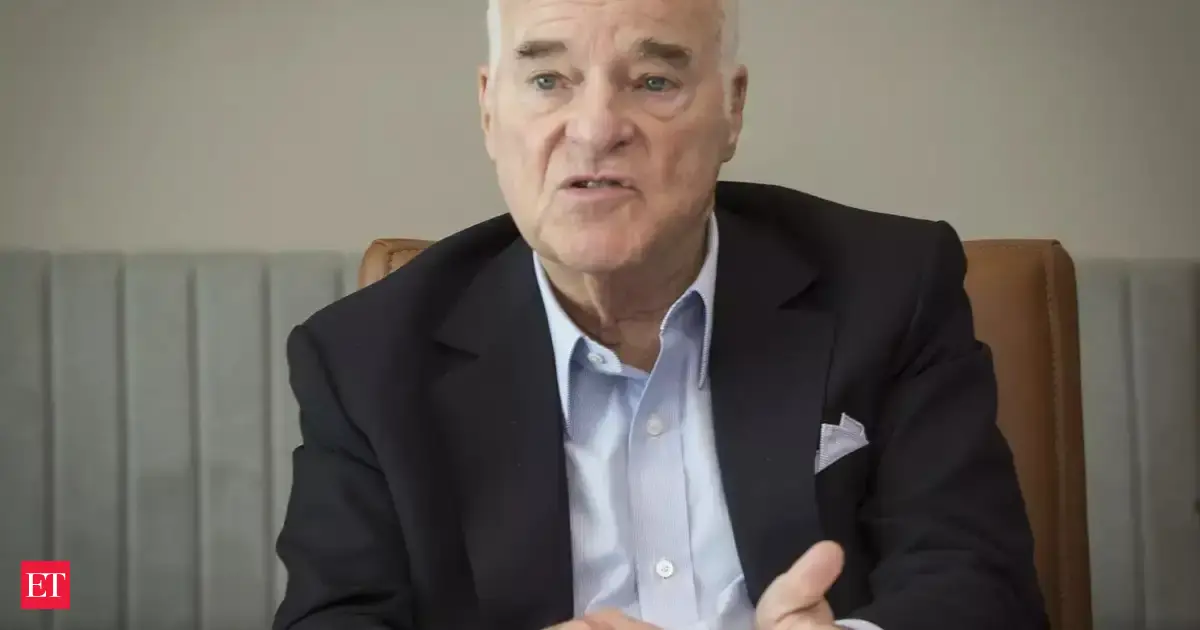

Somani’s perspective centers on a concept he calls debuggability: the ability to localize failures, intervene predictably, and verify that interventions are preserving the desired behavior on bounded domains.

This is not the same as interpretability, at least in the conventional sense. That’s because debuggability doesn’t require a simple story about why a model behaves a certain way. Instead, it requires the capacity to identify which internal mechanisms drive a given behavior, to modify those mechanisms precisely, and to demonstrate that the modification works as intended without causing collateral damage.

The distinction here matters, mainly because it shifts the focus from understanding to control. A CEO doesn’t need to know every detail of how a recommendation engine works. But they do need confidence that when the engine misbehaves, their team can fix it without guesswork.

Achieving this level of control demands three things: localization, intervention, and certification.

Localization

Localization means identifying which specific mechanisms within the AI system are responsible for a given behavior, and distinguishing mechanisms that generalize from those that merely correlate.

This goes beyond identifying which model or layer produced an output. It requires the ability to ask whether the behavior could occur without the mechanism being active, or whether the mechanism could be active without producing the behavior.

Intervention

Intervention means modifying the responsible mechanism in a way that is both predictable and targeted. The modification, as Somani knows, should remove the undesired behavior on a specified domain without inducing failures elsewhere in that domain.

This is often where AI systems break down. Interventions that seem reasonable in isolation can create cascading effects that can actually render the fix worse than the original problem.

Certification

Certification means making exhaustive, falsifiable claims about model behavior on bounded domains. This means that, for a formally specified set of inputs, it should be possible to prove that certain output classes cannot occur, or that specific internal pathways are structurally incapable of bypassing safeguards unless explicit conditions are met.

These are not distributional or probabilistic guarantees. They are universal claims over defined scopes. The difference is critical. Probabilistic assurances tell you that something is unlikely to fail. Certification tells you that it cannot fail in a particular way within a particular domain. If it does, the certification itself was wrong.

Why This Matters for Governance

For executives, the implications are clear.

Traditional risk management relies on transparency, auditability, and the ability to trace decisions back to accountable individuals. And when AI systems operate as black boxes, these mechanisms erode.

Fortunately, regulatory frameworks are beginning to catch up. For instance, the European Union’s AI Act, along with emerging standards from organizations like NIST, emphasizes the need for explainability, accountability, and human oversight.

But compliance alone is not sufficient, because an organization can pass an audit while still lacking the capacity to fix its systems when they fail in the field.

Debuggability shifts the conversation from compliance theater to operational capability. It asks whether your organization has the technical infrastructure to do three things when an AI system misbehaves: 1) identify the root cause, 2) modify the system with confidence, and 3) verify that the modification worked.

Without these capabilities, governance becomes reactive and fragile. Leadership can mandate reviews, require documentation, and impose oversight, but none of these measures prevents the underlying problem.

When a system fails, the organization is left with guesswork, costly rollbacks, or acceptance of known flaws.

The Software Analogy

Somani likens the issue to large, safety-critical software systems. While no one can prove that a web browser will never crash, it is possible to prove that specific routines are memory-safe, that sandboxing prevents certain classes of exploits, that critical invariants are preserved across updates, and that a given patch eliminates a vulnerability without introducing regressions.

The same logic applies to AI. Meaningful control consists not in global guarantees, but in compositional, domain-bounded assurances. These may include ensuring that a subcircuit cannot activate a forbidden feature on a specified input domain, or that an intervention will remove a failure mode while still preserving all other behaviors in scope. It may also include providing confidence that a pathway will be structurally incapable of bypassing a guard unless a specific internal condition is met.

These are the kinds of claims that matter for organizations deploying AI in high-stakes environments, such as in finance, health care, supply chain optimization, or content moderation. They allow leadership to make decisions with confidence rather than hope.

The Path Forward

Ultimately, achieving debuggability requires investment in methods that most organizations have not prioritized.

One such method is formal verification, which uses mathematical proofs to establish properties of software. Traditionally applied to narrow, safety-critical systems such as aircraft controllers and cryptographic protocols, extending these techniques to AI, while technically challenging, is not impossible.

Recent advances suggest a path. Sparse circuit extraction shows that large models contain relatively isolated subcircuits that remain stable under intervention. Neural verification frameworks demonstrate that exhaustive reasoning is possible when models are decomposed into verification-friendly components on bounded domains. Alternative attention mechanisms suggest that architectural choices that currently block verification are not fundamental requirements.

Now or later?

For organizational leaders, the question is whether to wait for these methods to mature or to begin building organizational capacity now.

Unfortunately, waiting carries risk. AI deployment is accelerating, and the gap between what organizations are deploying and what they can control is widening.

The alternative is to build capacity, which means investing in teams that understand both AI and formal methods, establishing internal standards for when debuggability is required, and partnering with vendors that prioritize verifiable systems over black-box convenience.

It also means changing how procurement and deployment decisions are made. When evaluating AI tools, the default questions focus on accuracy, speed, and cost. Debuggability adds a fourth dimension: Can we fix this if it breaks?

Reframing the Conversation

Most discussions of AI risk focus on external threats, such as adversarial attacks, data poisoning, or misuse by bad actors. These are legitimate concerns, but they distract from a more fundamental issue.

The primary risk for most organizations is not that someone will weaponize their AI. It’s the possibility that the AI will fail in ordinary operation, and the organization will lack the tools to respond effectively.

This is a governance problem, not a technology problem. And it requires leadership that understands the difference between explanation and control, between compliance and capability, and between probabilistic assurance and formal verification.

Somani’s argument is that the endgame for AI risk management is not better monitoring or more oversight. Instead, it’s building systems that can be debugged with the same rigor that safety-critical software demands today. Until that becomes standard practice, organizations are deploying systems they do not truly control.

For CEOs, the imperative is clear. The question is not whether AI will transform your industry. It already has. The question is whether your organization will have the capacity to govern it when it matters most.