In a recent post, Scott Alexander doubled down on his argument that building more housing generally results in higher housing prices. In his previous post, he pointed to the fact that housing is generally more expensive in bigger cities. I provided a counterexample, citing Houston and Austin. I also argued that big cities are expensive for reasons unrelated to their large quantity of housing, such as the advantages provided by agglomeration. Exogenous supply increases, such as making it easier to build new housing, generally reduce housing prices.

Here’s how Alexander responded to one of my arguments:

I started the post with a graph of about 50 cities, showing a positive correlation between density and price. I’m having trouble seeing how Sumner’s point isn’t just “if you remove 48 of those cities and cherry-pick two, the relationship is negative”.

I think Alexander misunderstood this argument, so let me go back and make the point more carefully. It will be helpful to make two separate arguments:

1. You’d expect big cities to be more expensive even if building housing reduces housing prices.

2. Austin and Houston are not the only counterexamples; there are many other such anomalies.

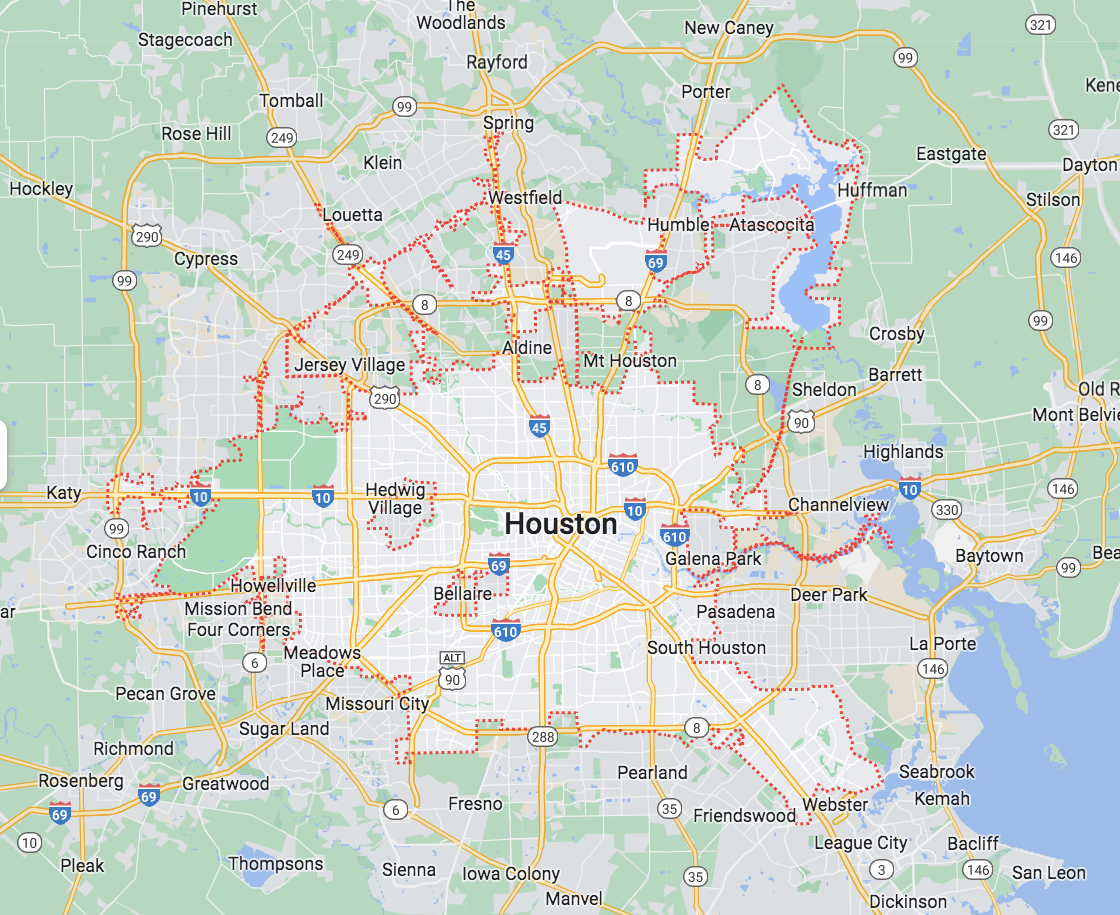

Let’s start with a simple model where there are zero restrictions on housing construction in all cities. Assume that America has 100 cities, each with industries of varying productivity. In that model, the largest cities will be next to the areas of greatest productivity. (Those areas of productivity were once linked to natural factors such as ports and mineral resources, but are increasingly linked to industries with network effects like finance, energy, entertainment and tech.) Again, assume there are no barriers to building, that is, construction of housing is so unconstrained that every single city makes modern Houston seem like a NIMBY stronghold.

Housing prices in this hypothetical economy will be higher in the larger cities, ceteris paribus, even though building additional housing might well depress prices. That’s because in a larger city, people will pay more for convenience (i.e., a good location). That would be true even if those bigger cities were not more productive. For instance, people would pay extra to reduce commuting costs, or to be close to amenities. But the bigger cities are (by assumption) also more productive, which provides another reason for housing prices to be higher in bigger cities—higher wages. This thought experiment suggests that the empirical relationship Alexander relies upon to make his argument would apply even if his argument were not true.

One response is that these industries with network effects only exist in places like New York because there are lots of people, and that you can’t have lots of people without lots of housing. That’s true, but has no bearing on the question of how additional housing affects prices at the margin. And from the previous thought experiment, it’s clear that looking at simple correlations doesn’t resolve that problem.

Alexander might reasonably respond that my model is overly simplistic. Building restrictions differ from one city to another. In that case, you might expect some exceptions to the iron law that bigger cities are more expensive than smaller cities. And since (he assumes) I found only one such anomaly, the correlation among the remaining cities is too strong to explain by (exogenous) factors other than city size.

Actually, I cited Austin and Houston merely as one example, and I picked this example because they are located in the same state. In fact, there are many, many examples of larger cities that are cheaper than smaller cities. And in virtually every single case the explanation is that the smaller but more expensive cities have more restrictions on building. In the list below, the metro areas on the left are larger and cheaper than the metro areas on the right:

Chicago >>> San Francisco Bay Area

Dallas/Forth Worth >>> Washington DC

Houston >>> Boston or Seattle

San Antonio >>> Portland

Phoenix >>> San Diego

Colorado Springs >>> Boulder

In each case, the larger metro area is cheaper than the smaller one. And in each case there are stricter limits on building in the more expensive city.

That doesn’t prove Alexander is wrong. It’s possible that the reason for more expensive housing in the NIMBY cities has nothing to do with restrictions on building. But I doubt it. I suspect that if Houston had adopted severe restrictions on building in the 1980s, then people would now attribute the resulting high housing prices as being due to all the oil money sloshing through its economy. But Houston decided to open its doors to anyone who wished to move there. As a result, even though Houston is the global energy capital and is full of well paid petroleum engineers, and even though energy is one of the world’s largest industries, Houston is still a cheap place to live. Instead, it got much bigger. BTW, Houston also has well paid aerospace engineers, well paid business executives and well paid doctors, etc. There’s more than enough money in Houston to drive up housing prices if they had restricted building.

It may appear that Alexander is “Reasoning from a quantity change.” After all, it makes no sense to discuss the impact of a change in quantity on price, without knowing why quantity changed. If Oakland gets more housing because it deregulates, prices will probably fall. If Oakland gets more housing because it becomes trendier, then prices will probably rise. Alexander seems to understand this problem, and thus at least implicitly seems to believe that every single factor that might boost Oakland’s housing supply would have the effect of boosting demand by more than supply. That is, he seems to believe that NIMBY policies make cities cheaper. That’s theoretically possible, but seems unlikely in most cases.

To recap my argument:

1. The correlation Alexander cites proves nothing—you’d expect bigger cities to be more expensive even if (at the margin) building more housing did not raise prices.

2. Alexander is correct that if his model were wrong then you’d expect some exceptions to the generally positive relationship between density and price, due to differential restrictions on building. But plenty of such exceptions do exist, and almost always in exactly the places predicted by YIMBY proponents of more building. Elsewhere in his post he dismisses intercity comparisons between trendy coastal cities and heartland cities. Nonetheless, the examples I provide show that I didn’t just cherry pick one exception with my Austin/Houston comparison, there are many such anomalies. And one can find such anomalies even within coastal areas. The Bay Area is more expensive than LA, despite being smaller. It has more restrictive zoning. The Boston metro area is more expensive than metro DC, despite being smaller. Boston has more restrictive zoning. And you can’t say that LA and DC are not desirable markets.

Just to be clear, our dispute has absolutely no policy implications. For instance, I said:

If building more housing raises its price, then the argument for more construction is even stronger.

And Alexander responded:

I agree with all this.

This is important, because his previous post had seemed to indicate that he thought it was a “problem” that new construction led to higher housing prices. He previously said:

This is a coordination problem: if every city upzones together, they can all get lower house prices, but each city can minimize its own prices by refusing to cooperate and hoping everyone else does the hard work.

What “hard work”?

In the new post he makes it very clear that this is not a “problem.” He supports the YIMBY position.

Thus we both support making it easier to build housing in Oakland, although he thinks this would raise prices and I think it would lower them. If I’m wrong, that is, if more housing boosted house prices in Oakland, then we both agree that this would be an especially good result. And I concede that I might be wrong.

P.S. Slightly off topic, it’s worth recalling why new houses should be “unaffordable” for average Americans. Think of a steady-state society with only 100 families, living in 100 houses of varying quality. Assume that each house lasts 100 years. Each year, the worst house is torn down, and a new house is built. In order for the quality of the housing stock to rise by 1%/year, the new house must be twice as good as the average existing house. Each year, the families all shift over one house, moving gradually to better and better properties. The richest family lives in the newly built house, which is (by assumption) unaffordable to the other 99 families.

In a more realistic model with population growth, not every new house is unaffordable to the bottom 99%. But even with population growth, new construction in an economy with rising living standards will tend to be much nicer than the existing stock of housing, which means that new construction will generally be “unaffordable” to the average family. If new housing is affordable to the average family, then society will not progress.

P.P.S. Alexander describes my previous post as follows:

Scott Sumner is an economist and blogger

I don’t see myself as a famous person, but I share his view that I have the potential to hold good opinions. As far as the question of whether I do actually hold good opinions, I’ll let readers decide.