Mark Twain is often credited with saying: “History doesn’t repeat itself, but it often rhymes.”

This week feels like the second, incomplete line of a poem:

First Bear Stearns and Lehman Brothers both went under,

Then SVB and ____ tore investors asunder.

Silicon Valley Bank’s (SVB) failure rhymes with the 2008 financial crisis. Just not in the way everyone thinks it does.

This isn’t the famous “Lehman Brothers moment” when markets plunged into full-blown crisis.

This is the “Bear Stearns moment” from six months before, when everyone shrugged and whistled Hakuna Matata as they walked past the graveyard … ignorant as the undertaker dug fresh plots.

Back in 2008, those plots were reserved for banks that got wrapped up in the game of mortgage-backed securities.

This time around, they’re for the tech companies scraping dirt in the well of easy money.

Both times, many believed that the crisis would be contained quickly.

Both times, they’ll be wrong.

I’ve been warning about a Silicon Valley Shakeout all this year.

I want to emphasize that this was and still is a forward-looking warning. Despite huge losses in 2022, we have not yet truly seen the impact on the tech sector.

Today we break down exactly what happened, why it happened and why we aren’t anywhere close to the end of it.

Gradually, Then Suddenly: The Bear Stearns Collapse

Bear Stearns was a legendary Wall Street firm, operating for 85 years.

Its managers navigated the Great Depression. They prospered even in a 16-year bear market that started in 1966. They’d survived countless crashes and the internet bubble.

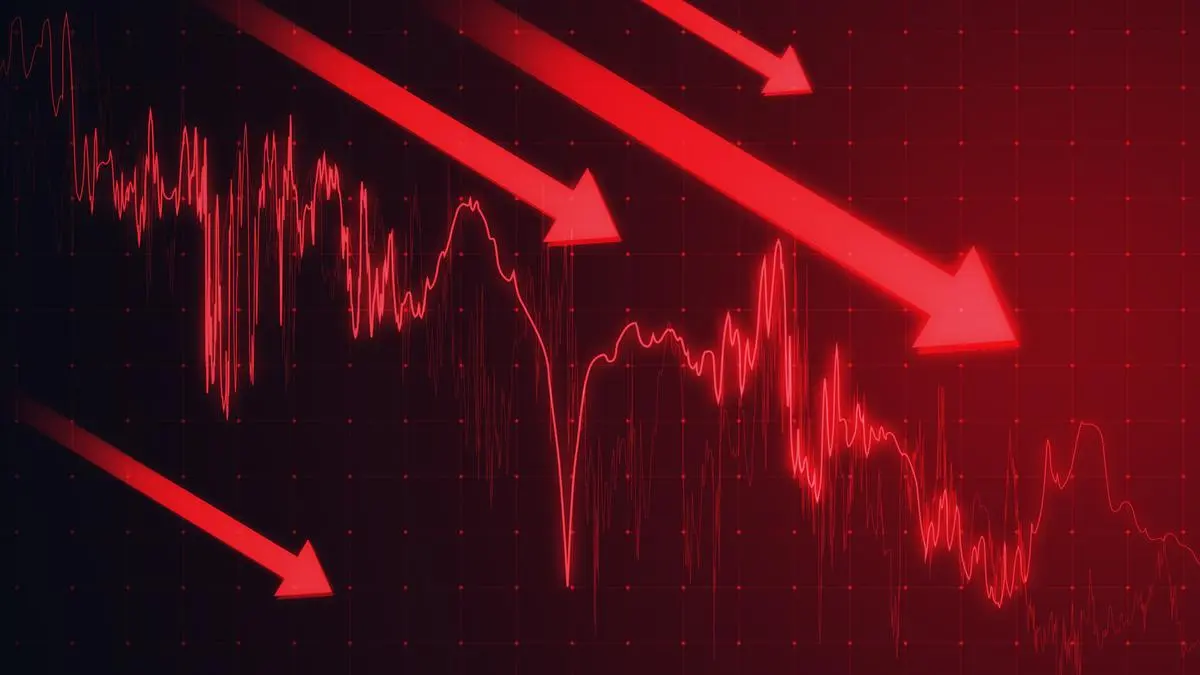

Yet the firm collapsed suddenly in 2008. Here’s a chart of Bear Stearns from back then, with the S&P overlaid in black.

“No one” saw it coming in February 2008.

The stock had fallen from $165 to $80 in a year. But it was the fall below $5 that caught everyone by surprise. That took just a month.

When Bear collapsed, the S&P 500 was near 1500. It rallied almost 12% in the next month. That sure made it seem like the worst was over.

But then Lehman Brothers collapsed six months after Bear. By then, investors and regulators knew things were bad. That news set up a six-month, 43% decline in the S&P 500.

With this in mind, let’s now look at a chart of Silicon Valley Bank and the S&P 500:

![]()

Like Bear Stearns, the collapse in SVB was gradual, then sudden. Thus far, its impacts have also been wide-reaching.

Today, many think SVB was the Lehman moment. I think it’s the Bear Stearns moment.

Bear’s collapse was caused by subprime mortgages. Other firms had exposure to those securities. In March 2008, they were hiding problems from investors. Within six months, we learned how widespread the problem was.

Last week, SVB collapsed because of a maturity mismatch. The bank needed cash to meet short-term obligations. Its cash was locked up in long-term securities it had bought at the worst possible time — when interest rates were low.

SVB had to do this after growing its deposits too fast because tech companies got free money from investors during the pandemic bubble.

When the Fed raised rates, free money stopped flowing. Long-term securities got crushed. Companies drew down their deposits.

And to meet its obligations, SVB had to take large losses in the long-term securities. That led to its collapse.

Now there are two important questions.

- How exposed is the rest of the banking sector?

- What does it mean for SVB’s customers?

The rest of the banking sector has a manageable problem, for now. About 11% of the bonds banks own are worth less than they paid for them. This won’t be an issue for most banks. Generally, banks expect to hold bonds to maturity. The loss will be erased by then.

Some banks who need cash, especially those serving small niches like tech and crypto, are at risk of collapsing.

But focusing on the banks is missing the big story.

The Beginning of the End

This week, everyone is focused on how that drawdown caused a bank to collapse.

They’re missing the fact that tech companies are burning through their cash at a clearly unsustainable rate.

Many won’t be able to raise more, because the policy environment that allowed many tech companies to even exist is long gone.

Low interest rates led to bad ideas being funded, because low safe yields forced the money to find a return somewhere.

The truth is we don’t need dozens of meal delivery services. Consumers can’t afford to pay for food, delivery, profits for the restaurant, a tip the delivery driver, the Silicon Valley whiz kids designing web pages and investors who keep those whiz kids employed.

We are at the beginning — not the end — of a Silicon Shakeout.

It’s inevitable. Few will survive. And smart investors need to act now to benefit from that.

There are ample ways to profit from the demise of companies in the tech sector. I’m already using these methods with my Precision Profits subscribers, resulting in gains of 29% in one day, 54% in one day and 57% in two days.

All of these gains came in just the last week, as the story with SVB unfolded.

If you’d like to join me or just learn more about Precision Profits, click this link.

Regards,

Michael CarrEditor, One Trade

Michael CarrEditor, One Trade

The worst aspect of the banking crisis we see unfolding this week is that we simply don’t know what happens next … or what the next domino to fall will be.

As Mike put it, a crisis like this unfolds gradually … then suddenly!

As I mentioned in yesterday’s Banyan Edge, I think it makes a lot of sense to keep any cash you hold at the bank below the FDIC-insured maximum of $250,000.

The government has, thus far, made it clear that it plans to bail out depositors of any banks that fail. And I think it’s unlikely they change their mind on that, as doing so would destroy confidence in the system.

But what if I’m wrong? What if the losses get too big, public sentiment shifts and the government decides that your bank is the one they choose not to prop up?

There’s just no reason to risk it. Spread your cash among different banks or sweep any excess cash into T-bills. You really don’t need to have $250,000 in cash anyway.

As Mike pointed out, what we’re seeing today is part of the Silicon Shakeout.

America’s tech companies were addicted to cheap capital, but that capital is no longer cheap. Now, the failure of Silicon Valley Bank promises to make capital even more expensive for tech companies, as it was a major source of funding for young tech.

Mike has been looking for opportunities to sell rallies all year, and Adam’s Big Short puts him in the same camp.

I agree. But let’s also look at this another way … looking for assets that will go UP in this environment.

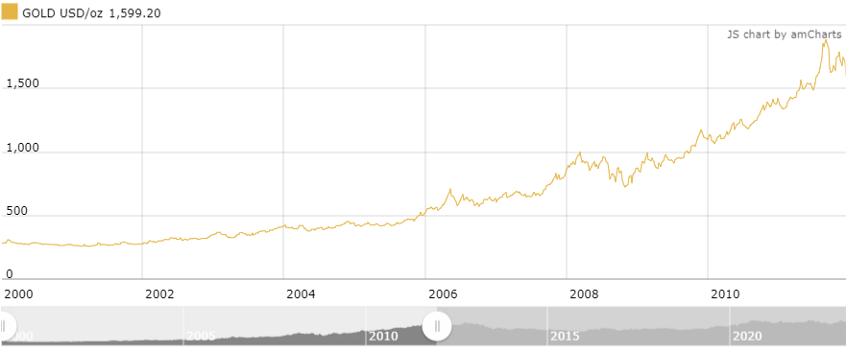

The last time we saw a shakeout in technology shares (in 2000), it marked the beginning of an epic bull market in gold.

In early 2000, the spot price of gold was less than $300 per ounce. By the time in peaked in 2011, gold was trading at close to $1,900. Any investor riding that wave would have seen returns of well over 500%.

Gold also provided a safe haven during the 2008 banking meltdown, dipping only slightly during the crisis and recovering to new highs in no time at all.

I’m not suggesting you dump your entire portfolio into gold. I would never do that. Because gold, just like any other asset, can be volatile.

But given the convergence of events we see today — a continued meltdown in tech coupled with a distressed banking sector — doesn’t having a little exposure to gold make sense?

You can get this done any number of ways. Gold ETFs, mining companies or royalty-streaming companies are all solid options to diversify into.

But there’s nothing better than holding an ounce of gold in your hand — or at least knowing you could take delivery of it at any time.

Our friends at Hard Assets Alliance are your best bet for that level of gold ownership. They offer all types of precious metal bullion at attractive premiums, while also providing a best-in-class vault storage both in the USA and abroad.

But the best part of working with HAA is how easy it is to use their platform. You can buy or sell precious metals from your portfolio just as easily as buying a stock, and with just the same liquidity. It’s no surprise over 100,000 investors have entrusted HAA with $3 billion in precious metals for the last decade.

Right now, HAA is offering Banyan Edge readers six months of free vault storage on new bullion purchases. Click here to check out what they have to offer and start securing your wealth today.

Regards,

Charles SizemoreChief Editor, The Banyan Edge

Charles SizemoreChief Editor, The Banyan Edge