I don’t believe that it makes sense to speak of the true rate of inflation. After all, no one seems to know what inflation is supposed to be measuring. Some economists might argue that it represents the increase in pay you’d need so that you are not worse off in terms of utility. But what does that mean?

Suppose I met a Gen Zer who said he rather earn $100,000 today than $100,000 in 1955 (when I was born.) After all, today he can have better medical care, better Asian cuisine, better TVs, the internet, smart phones, etc., etc. Would that imply that there had been no rise in the “cost of living” since 1955, at least for that individual? In my view, that would be a silly way to view inflation. But given textbook definitions, how can I say he’d be wrong?

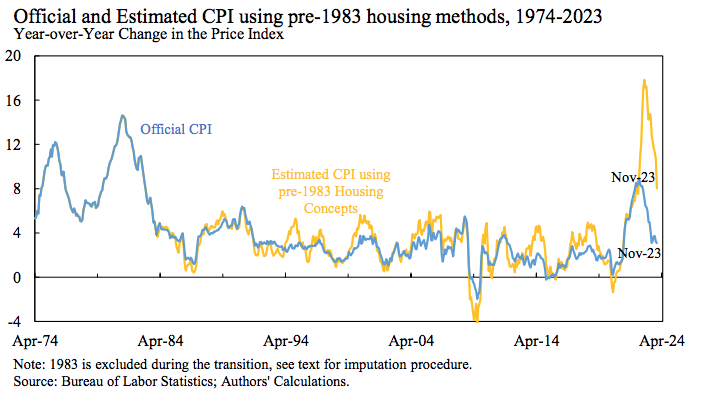

If I’m correct that inflation is somewhat subjective, I’d still insist that some price indices are more useful than others. Josh Hendrickson directed me to a paper by Marijn A. Bolhuis, Judd N. L. Cramer, Karl Oskar Schulz, and Lawrence H. Summers (BCSS), which estimates recent inflation using the techniques that were used prior to 1983. They put more weight on things like financing costs, which have risen sharply during a period of rising interest rates:

In their revised estimates, 12-month CPI inflation peaked at 18% in November 2022, and remained at 9% even in November 2023. (The official figures show CPI inflation peaking at only 9.1%.) Unless I’m mistaken, the revised data implies a 28.6% total increase in the CPI between November 2021 and November 2023. Let’s compare that to some other data points:

Revised CPI: +28.6% between 11/21 and 11/23

Nominal GDP: +13.4% between 2021:Q4 and 2023:Q4

Nominal consumption: +12.9% between 11/21 and 11/23

Nominal average hourly earnings: +9.6% between 11/21 and 11/23

Taken at face value, a 28.6% rise in the price level at a time of much slower nominal growth implies that the US fell into one of the deepest depressions in US history. In fairness, it’s not quite right to compare the CPI with nominal GDP, as the CPI only measures the price of consumer goods. You need the GDP deflator.

But notice that nominal consumption rose even more slowly than nominal GDP (although both are actually growing rapidly by 21st century standards). So if the revised CPI figures are true, then it seems as though real consumption must have plunged at an astounding rate—comparable to a major economic depression such as the 1930s.

I suppose one could argue that the same techniques that BCSS used to adjust the CPI might also impact nominal aggregates such as consumption and NGDP. Even so, it’s hard to believe that any plausible adjustment in aggregate consumption growth could even come close to closing the gap with the revised CPI inflation estimate.

In addition, any problems with nominal consumption would not bias the estimate of nominal average hourly earnings, which rose by only a total of 9.6%. I suppose it is technically possible that nominal wages rose by 9.6% at a time the cost of living rose by 28.6%, but what would that imply about the rest of the economy? Wouldn’t that imply a major economic crisis where workers were unable to afford anything more than the most basis necessities? And yet, everywhere I look I see evidence of a booming economy.

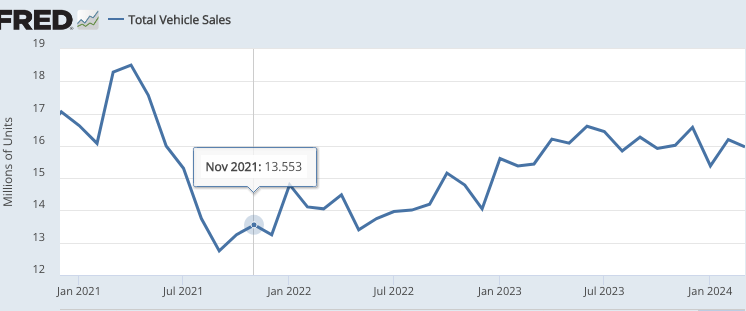

To take one example, car sales tend to fall sharply during “hard times”. And yet car sales have increased sharply during this period of rising interest rates:

And car sales are generally far more cyclical than other types of consumption like health care, education and haircuts. Why have they risen sharply since November 2021?

All our economic data points suggest strong output growth. The job market is extremely strong, with low unemployment and very robust growth in total employment. If you adjust for demographics (the aging population), then the employment-population ratio is back near the peak levels of 1999-2000.

If you ask people why we need inflation estimates, they’ll typically say something to the effect that inflation adjustments allow us to figure out how the economy is actually performing, without the distortions created by a declining purchasing power of money. In other words, we use inflation to convert nominal variables into real variables. But when I try to apply the BCSS inflation estimates to any sort of plausible nominal variable in the US economy, I come up with real variables that literally make no sense.

To be clear, this is not a criticism of the BCSS paper, which focuses on one very narrow question—why is consumer sentiment so poor, despite a strong labor market? They may be correct in claiming that rising financing costs largely explain the public’s surprisingly sour mood.

Rather, my argument here is that these inflation estimates are not useful in a conventional sense. If we try to use them to convert nominal variables into real variables, we end up with nonsense. What am I missing?